Universities are not doing enough to reduce the number of research proposals submitted to the Dutch Research Council (NWO) and boost the chances of research funding.

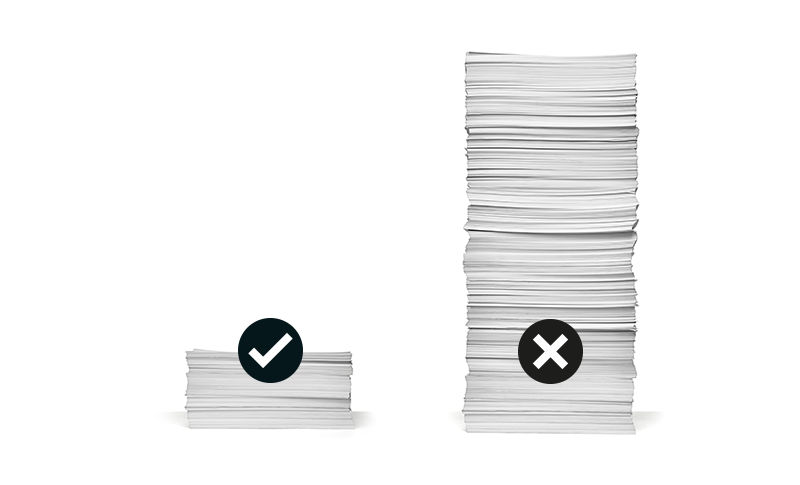

For years, Dutch researchers have been complaining that they have to submit endless research proposals to funding bodies, without success. In the Talent programmes and National Science Agenda run by the Dutch Research Council (NWO), for example, only 15 to 20 per cent of all applicants get funding. The rest have then written their proposal for nothing.

The WUR course for applicants for Veni and Vidi grants pays off

The Research Council and the universities have been saying for years that something should be done about that low success rate. In 2017, they agreed that the universities would make a pre-selection of research proposals so that fewer proposals would reach the NWO, increasing the success rate of those that were submitted.

Four years later, it appears that nothing came of that agreement. In 2017, the universities submitted 5730 research proposals between them, NWO figures show. In 2020, that number was up to 6803 proposals. Wageningen University submitted 299 proposals in 2017, and 273 four years later. So WUR did not contribute to the rise in proposal numbers, but it can hardly claim to have been selective.

So what is holding the universities back? They are not interested in playing at being a mini-NWO, because that costs money without increasing their income from research. What is more, they are in a catch-22 situation: if you start pre-selecting and other universities do not, you are likely to get fewer research projects funded by the NWO.

Quota

Nevertheless, the universities have been supervising the process more over the past four years, says Henrieke de Ruiter, who coordinates the applications for NWO funding at the WUR Grant Office. The NWO has established quota in several large research programmes such as the Gravity Programme and the Long-term Programme (LTP). That means that if there are a lot of candidates, the universities are forced to assess and select from their own proposals.

WUR has also set up an internal procedure for researchers applying for a Veni or Vidi grant from NWO. The Veni grant is personal funding for recent PhD graduates, and the Vidi is for experienced researchers. Applicants can take a course on what to pay attention to in an application, and a panel of experts assesses their proposal before it goes to the NWO. This approach pays off, says De Ruiter.

A lot of researchers don’t take the time to read the guidelines of research funding bodies carefully

The success rate of WUR researchers who applied for a Veni grant in the past three years is much higher than the national average: 31 per cent as opposed to 14 per cent. The success rate for the Vidi grants was 29 per cent for WUR, compared to a national average of 18 per cent. The internal WUR procedure focuses mainly on improving research proposals, rather than selecting them.

But the majority of NWO programmes do not have quotas, nor do the universities have procedures for them, so researchers are still taking a scattergun approach, too many research proposals still come in, and the universities are still talking to the funding body about how to stem the tide of applications. The big question is: can the universities coordinate and select applications without taking over the work of the NWO?

Stepwise

At present, the usual approach to channelling the enormous stream of proposals is a stepwise procedure in which researchers or research groups write a brief proposal that is assessed in the first round. A small selection of these goes on to the second round, for which a fully worked-out proposal is required. This is a handy approach for large programmes with many partners who need plenty of time to coordinate their research. But even by this method, the NWO still receives a lot of applications, and honours few of them.

What else could be done? The researchers at the universities could make more effort to write fewer – and better – proposals, thinks De Ruiter. A lot of researchers don’t take the time to read the guidelines of research funding bodies carefully. They submit proposals without really knowing what the funding body wants to know, which research framework and jargon is required, and what conditions apply for obtaining funding. It can help to seek advice from experts at the Wageningen Grant Office. A less scattergun approach leads not only to better proposals but often also to fewer proposals.

Also read the respons of the NWO. ‘The greater issue is that there are insufficient funds available for research.’