The article ‘China and Wageningen are getting on fine’ in Resource on 5 November was read closely by many readers. Several of them sent in further elaborations and criticisms.

In the article, Wageningen scientists say they disagree with the studies that conclude that the long arm of China has Dutch research in its grip. They do concur that China keeps an eye on its students here.

The Wageningen PhD student Yongran Ji says there is no surveillance of most Chinese students and researchers in Wageningen by the Chinese embassy. The embassy only registers those with a grant and monitors what they achieve in exchange for their grant. Yongran, like most of the Chinese at Wageningen, pays his own way. He has been in Wageningen for eight years and has never reported anything to the Chinese embassy, he says. Lingtong Gai, who works for Wageningen Academy, states that the embassy’s so-called ‘surveillance’ is misinterpreted in the article: it is normal for an embassy to have a list of its citizens in higher education and research, and to organize events for them. Dutch embassies do the same.

But Rien Bor, formerly WUR’s international student recruiter, did notice that the Chinese embassy put pressure on Chinese students and WUR. For example, the embassy repeatedly objected to the Taiwanese presentation at Global Village Day, at which all the student nationalities in Wageningen present themselves. The embassy pressurized Chinese students to protest against this.

Phytopathologist Francie Govers had just finished reading the article about WUR and China when she came across a form of political influencing of an academic article. She was reviewing a publication by Chinese researchers about the potato disease Phytophthora. The article included a map of China to show where the researchers had collected their Phytophthora strains. In the first version they used the standard international map, but in the latest version they use the controversial ‘nine-dash map’ on which the islands in the South China Sea claimed by China are shown as Chinese.

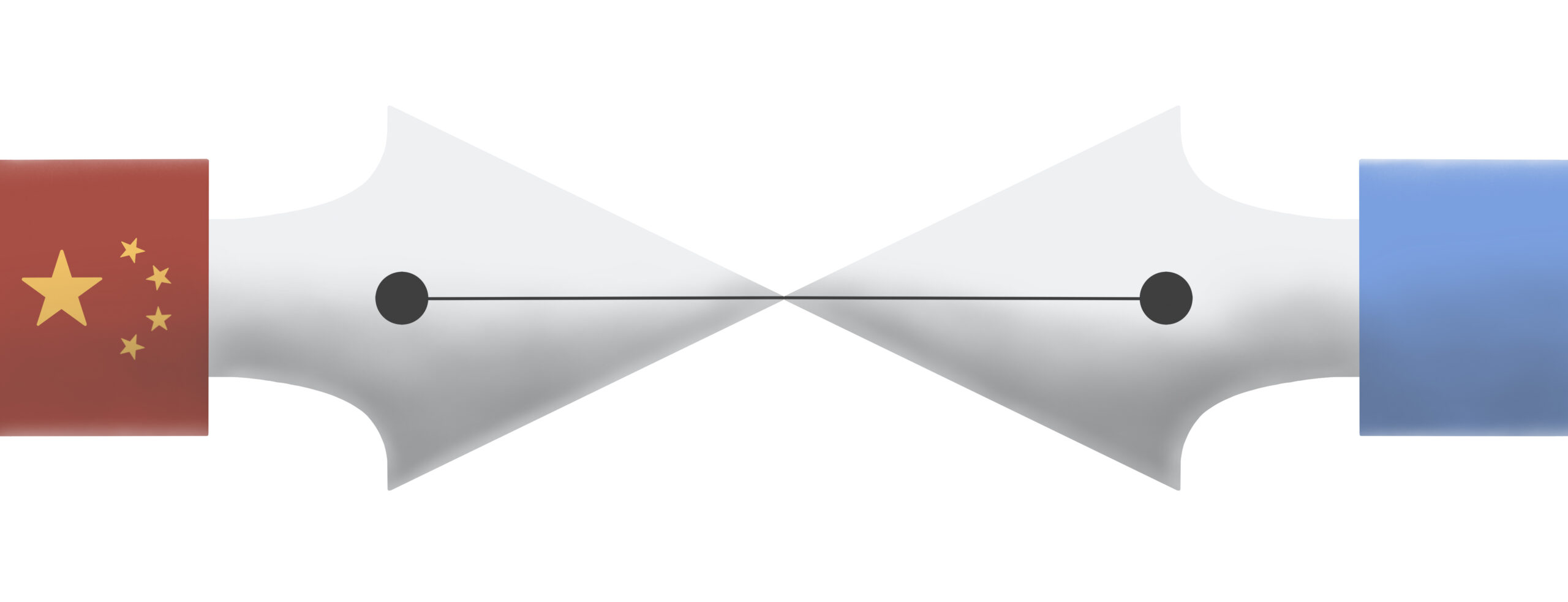

The other reviewer, who noticed this change, suspects the researchers had to change their map due to instructions ‘from above’. The reviewer sees this as politics getting mixed up with science, since the map with the disputed islands has nothing whatsoever to do with Phytophthora. And to Melanie Peters, director of the Rathenau Institute, the attitude of the Wageningen scientists quoted is naive. There is a technology war going on between the US, China and Europe, and in that context China is building large data centres for genetic research on humans, animals, plants and viruses so as to become a kind of Google for DNA, she says. Dutch universities need to watch out that that data is not misused by authoritarian states and multinationals. We’ll talk to Melanie Peters about this again in Resource #7, which comes out on 3 December.