We in the Netherlands commemorate the victims of war every year in 4 May. One of them was Hans Zomer, who was a student in Wageningen just before World War II. His young life came to an end at the hands of a German firing squad.

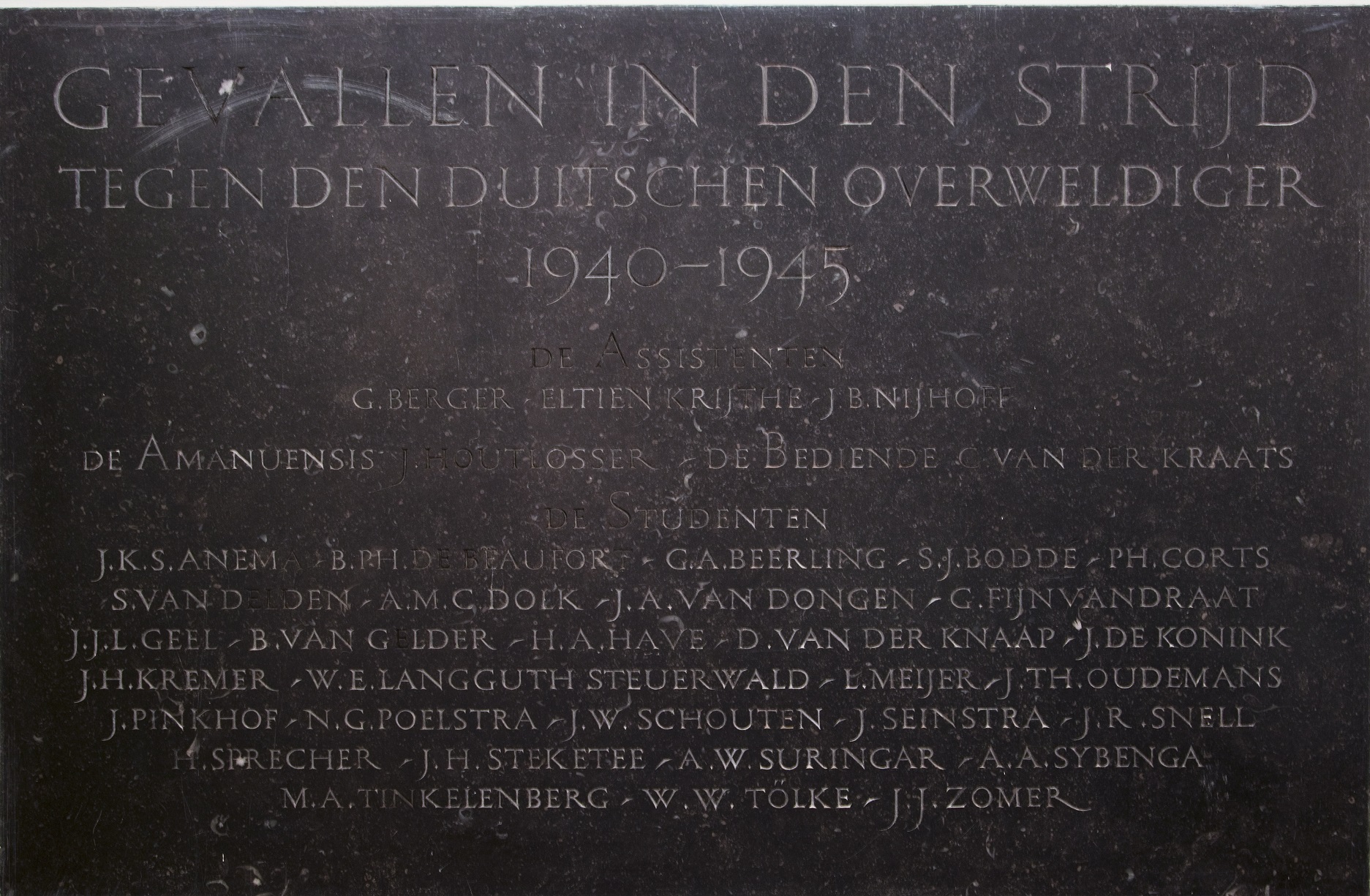

Johan Jacob Zomer, who went by the name of Hans, was one of the students and staff of the then Agricultural College who did not survive World War II. His name, along with those of 29 students and five staff members, appears on a plaque that hung in the Aula since 1946. A silent tribute to their bravery and the sacrifice they made. Hans Zomer had the courage to work for the resistance movement, and paid for it with his life.

Hans Zomer was born in Probolingo in East Java on 6 November 1920, the son of a naval officer. The Zomers had lived in Indonesia for three generations, until his father took a new job with the railways, got into a conflict there and left for the Netherlands with his wife and son, who was still a baby. ‘My mother, his sister Geertruida Catharina (Cathrien) Zomer, was born in Arnhem,’ says Hans van Tuikwerd. ‘The family lived in ’t Spijkerkwartier, which was still a good neighbourhood back then. Hans went to primary school and secondary school there.’

It is no coincidence that Van Tuikwerd’s name is Hans. The youngest in a family of four children, he was named after his uncle Hans Zomer. A fact he is proud of. ‘It means a lot to me. I used to look like him too. I’ve always been intrigued by his story.

I have just received the news that I have to say goodbye to you forever here on earth

I was born in 1956, not long after the war. I was fascinated by that period. I grew up in the shadow of the war, which had a huge impact on my parents. As his namesake, I want to honour Hans’s memory.’ So he keeps a small ‘museum’ in his study in his home in Hilvarenbeek, where a portrait of Uncle Hans hangs on the wall.

MI6

Hans Zomer only studied in Wageningen for one year. ‘After secondary school, he wanted to go to Den Helder and become a naval officer like his father,’ says Van Tuikwerd, ‘but they considered him too young at 17. That’s why he came to Wageningen.’ The yearbook of ‘38-’39 lists him as a first-year Tropical Forestry student. He was a member of Ceres and passed his first-year exams. In 1939, he tried again to get into the naval college in Den Helder and was accepted this time. So strictly speaking, Zomer was no longer a Wageningen student when the war broke out, having left a year earlier. But after the war, he had obviously not been forgotten here.

After the German invasion, Hans Zomer fled to England as a sergeant-at-arms. Van Tuikwerd: ‘He sailed for Falmouth on 14 May 1940 with 26 fellow midshipmen on the naval ship the Medusa. He was 19 and had only started his training eight months earlier.’ In the year that followed, he was recruited by the British intelligence service MI6. And so, on 12 June 1941, he was flown back to the Netherlands as a spy and radio operator, and parachuted into the Drenthe village of Vledder in the company of Wiek Schrage, a police inspector tasked with building a resistance organization. ‘They even seem to have sung the Wilhelmus before they jumped,’ he says. That was typical of Zomer, according to Van Tuikwerd. ‘Hans Zomer was not an adventurer. He was known as a bit of a loner, but as someone with a strong character. His actions were driven by a sense of duty. He was a Protestant and loyal to the authorities, the monarchy and the church. That was decisive in their letting him do this work at such a young age. He was given the opportunity to refuse, but he wanted to do it.’

Oranje Hotel

Little is known about the two months before his arrest, according to Van Tuikwerd. Zomer changed addresses often to keep away from the Germans. ‘He knew he could be detected while he was transmitting.’ His wanderings eventually brought him to the home of the Sickenga family in Bilthoven, whose son Jaap had also studied at Wageningen, one year before Zomer. Sickenga was collecting intelligence on the Soesterberg military airfield. That data was transmitted to England using Zomer’s equipment until the Gestapo traced the transmitter and picked them both up on 31 August (Queen Wilhelmina’s birthday). Zomer and Sickenga were taken to the infamous ‘Oranje Hotel’ in Scheveningen.

In late March 1942, a group of men including Zomer and Sickenga were transferred to Maastricht. A court martial followed at the Minnebroeders’ monastery. On 22 April, most of the group were sentenced to death for espionage and/or resistance. ‘After he was sentenced, he had a visit from his parents and my mother,’ says Van Tuikwerd. ‘He was very calm during that visit and asked them to be strong and trust in God. He still had hopes of avoiding the death penalty. He hoped they would take into account the fact that he was still a minor. He wrote a lot more letters from Maastricht.’

Forever

He wrote his last letter on 10 May. ‘I have just received the news that I have to say goodbye to you forever here on Earth. I cannot deny that it is a blow to me and not easy. But I am glad that I can still talk to you for a while.

He was given the opportunity to refuse, but he wanted to do it himself

Whatever happens, have faith in God’s omnipotence and God’s love.’ That night, the group of condemned men were put on a transport to an unknown destination. It was not ascertained until long after the war that Zomer and the others had been transported to Sachsenhausen near Berlin. There they were executed on 11 May, 15 hours after leaving Maastricht. ‘A classmate of Hans’s saw him arrive there,’ says Van Tuikwerd. ‘He reported it to the navy when the war was over, but the information nFever reached the family. It was terrible for my grandparents never to know where their son died.’

Hans Zomer was not forgotten, however. After the war, in 1946, he was posthumously awarded the Bronze Lion for bravery. In Wageningen, he was included on the above-mentioned commemorative plaque. The navy named a minesweeper HMS Zomer in 1961. (The ship has since been decommissioned.) In Maastricht, the execution of the 24 men is commemorated annually at a monument on the Patersbaan. Hans van Tuikwerd is there this year, as always. And he always wonders what he would have done. ‘Suppose this had happened to me, would I have been as steadfast? Would I have done what he did? Fortunately, thanks to the courage of Hans Zomer and others, we have never been faced with that situation again.’

Poet

Jaap Sickenga (1918) studied in Wageningen in the year 1937, after which he pursued a degree in Dutch in Amsterdam. Along with Hans Zomer, he was arrested for espionage in his parental home in Bilthoven. In the weeks between his death sentence and execution, he wrote poems from prison in Maastricht. He dedicated them to his fellow prisoners. The poem below (in translation) is on the monument in Maastricht to the 24 men executed at Sachsenhausen.

We are threatened

By a different death

Than by the bullet –

Indifference.

If you succumb to that

You die before your time.

Jaap Sickenga 2-2-1942

Portrait of Hans Zomer. Artist unknown, photo Roelof Kleis

Portrait of Hans Zomer. Artist unknown, photo Roelof Kleis