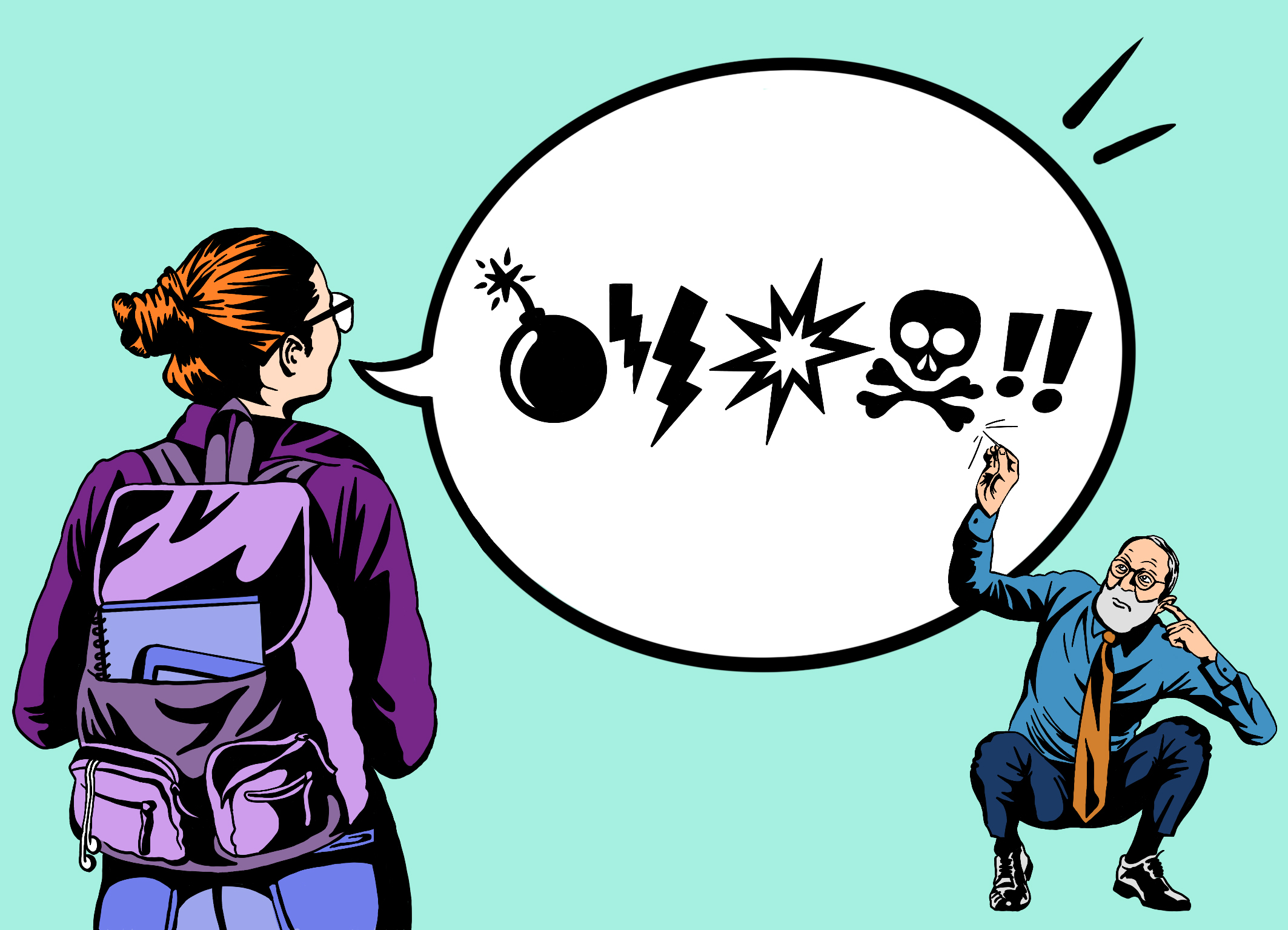

Course evaluations: once created to improve education, a small number of students seem to use them mainly to let off steam with hurtful remarks. ‘I wonder if they realize how much impact that has on lecturers’.

‘It’s pure bullshit that we have to learn this’; ‘that teacher is a worthless character’; ‘I don’t want to be mean, but she’s not a very good teacher. Everything around her was chaotic and badly prepared and all the practicals she gave went wrong’.

These are just a few of the comments in course evaluations that are difficult for lecturers to use to improve their teaching, but which do have an impact. Jan Kammenga, personal professor of Nematology, drew attention to this phenomenon in the [no]WURries feature. ‘It’s a question of a small group of students who do not observe normal standards of decency in the anonymous course evaluations. Maybe they think their comments disappear into the cloud and nothing is done with them. But that’s not the case. They really do go to the lecturer, who then reads at the end of the day that the course they teach is “bullshit” or that they are a “worthless character”.’

Mental pressure

Organic Chemistry lecturer Tjerk Sminia recognizes the picture sketched by Kammenga. ‘There is nothing wrong with criticism in itself, but if you or your colleagues are slandered, it affects you enormously. Most students respond in a civilized way, but every time a course is evaluated there is some unpleasantness.’ A case in point was a recent evaluation about Organic Chemistry 1, in which someone wrote a whole A4 about why that course was ‘total bullshit’. Sminia: ‘According to this first-year student, the content of the course was bad, the lecturers were bad, in fact everything was bad. There was nothing in it that we could use to improve the course. And this is one of the highest rated major courses taught here. Maybe it has something to do with the distance that grew up between teachers and students while we were teaching online.’

Maybe it has to do with the distance that grew up between teachers and students while we were teaching online

Dean of Education Arnold Bregt has also heard about the increasing number of discourteous responses in course evaluations. ‘If you have worked very hard to get things done, especially in the Covid period, and you get severe criticism that you can’t defend yourself against, it is a tough blow to take.’ Often it is only a small number of students who let off steam in a rude way, says Bregt. ‘But research into feedback shows that negative comments have five to ten times more impact than positive comments. This is not Twitter, and maybe we should remind students of that. Keep the criticism constructive. Then we can do something with it.’

Keep the criticism constructive, then we can do something with it

Harmful to careers

The course evaluations are intended to improve courses, but they are also used to assess the performance of lecturers on the tenure track and those working towards the Basic Teaching Qualification (BKO). Sminia: ‘And if you are new, don’t have a permanent contract yet, and you know that the course evaluations go to programme directors, programme committees and so on, then in addition to coping with these comments you also have to worry about the possible consequences for your reputation and your career.’ Kammenga sees this as problematic too. ‘This makes for far too much mental pressure on young lecturers.’

Associate Professor of Animal Ethics Bernice Bovenkerk was a member of several working groups on course evaluations. She thinks they have become too important over the years. Bovenkerk: ‘It is good for a chair holder to know that a certain course is not scoring very well and how it can be improved on, but it’s no more than that.’ She doesn’t think the evaluations should be used to assess the performance of lecturers.

After all, they tell us little or nothing about the lecturers’ capacities, Bovenkerk says. ‘And yet they are used in Wageningen to make decisions about promotions. The student evaluation working group brought this up a few years ago, and advised against it, particularly in the context of tenure track. Last year we wrote a letter about it as members of Wageningen Young Academy. But it still happens.’

Research by Troy Heffernan (Abusive comments in student evaluations of courses and teaching: the attacks women and marginalised academics endure) shows that course evaluations cause added stress and increase the risk of burnout, especially among people who do not yet have a permanent contract. Bovenkerk: ‘It is bad for teachers’ self-confidence. I’ve had colleagues crying on the phone because they got a couple of bad evaluations. One colleague reported that she felt increasingly insecure in front of the class. Then you end up in a vicious circle. It’s a high price to pay for an instrument that isn’t of much use anyway.’

Biased

Heffernan’s research also shows that a disproportionate number of women and minorities are the victims of these anonymous comments. Bovenkerk: ‘With women, for example, there are far more references to their appearance, and women get called “the teacher” and men “the professor”. We use a far too biased method of determining whether someone will or will not receive a promotion. It is discriminatory. It might be better to give study associations a role. They can discuss a course with students and discuss the findings with the lecturer later. We tried that once and it worked very well.’

Evaluating less frequently can also help, suggests Bovenkerk. ‘If courses receive poor evaluations or are new, you can scrutinize them more often, but with courses that score well year in year out, you really don’t need to do it every time.’ That may also improve the way students respond, Bovenkerk thinks. ‘Students are asked to give their opinion after every period; perhaps they are a little tired of evaluations and that can influence how they answer. Research also shows that students give higher scores when the sun shines than when it rains. It is context-dependent.’

New system

Would it help to include clear instructions with the course evaluations? Bovenkerk: ‘There is already some text about what they are for, but I doubt whether students read it. When I teach, people often ask questions to which the answer is in the study guide. It would make more sense to teach students about how to give feedback.’

Bregt too is critical of the use of course evaluations to assess lecturers. ‘We are working with the Recognition and Rewards working group on a new system in which lecturers can choose how they show they are qualified. They can use the course evaluations for this, but they don’t have to: it can be done by having conversations with students who indicate whether they have learned something, or by other forms of evaluation.’ Bregt hopes that the new teacher evaluation system will be launched in early 2023.

As far as Kammenga is concerned, one thing at least must happen with the course evaluations. ‘We have to start a conversation about them. Because it has got to change, that much is clear. The question is, how.’

Course evaluations in brief

At the end of each course, students are asked to fill in a course evaluation. They receive an invitation in their WUR email and answer questions in PACE, a tool for educational evaluations. Participation is anonymous, so students feel safe to express their criticism.

The course evaluations contain a number of closed questions. In these, students can indicate how a course scores in different areas on a scale of 1 to 5. There are also a number of open questions.

PACE summarizes the results, showing the average grades and the answers to open questions. These results are then sent to the lecturers, programme committees, programme directors and others involved in the course.

The course evaluations are intended to improve the course, but they are also used to assess the performance of lecturers. There is criticism of this, partly because it is easier to achieve higher scores for, say, a small MSc course with a nice excursion than a compulsory BSc course with hundreds of students.

Illustration: Valerie Geelen

Illustration: Valerie Geelen