The idea of printing food still sounds futuristic. But it’s a future that is rapidly approaching. And WUR is in the vanguard. Whether it’s plant-based burgers or personalized diets.

To begin with the most exciting story: standing in the experimental zone in Axis is a machine that prints burgers. The size of a small car, it prints a plant-based meat substitute. This machine is still top-secret. But it’s there, and it is nearly finished, says food technologist Martijn Noort. He coordinates the 3D-printing activities of the Digital Food Printing Initiative – more on this in a moment. The expectation is that the printer will be presented next year.

This will fulfil the wish of an anonymous donor, who gave WUR over a million euros for this development last year. ‘The assignment was to speed up the 3D-printing of plant-based meat substitutes. To come up with the formula for producing a meat substitute from plant protein with a 3D printer. A vegetarian burger with better sensory characteristics than the ones that are currently on the supermarket shelves. The bite and the juiciness are the main things. We are 90 per cent done. It’s a successful project.’

Pleasantly surprised

But WUR is not the first past the post. That was the Israeli company Redefine Meat, which for the past two weeks has been supplying the top Amsterdam chef Ron Blaauw with the first printed cuts of meat. The company is opening a factory in Best, in the Netherlands, and aims to be supplying the new meat to a wider range of customers by the end of this year. Noort honestly admits to being taken by surprise by that development. ‘But pleasantly surprised. Ultimately, it’s our mission that this sort of thing comes. They are working with the same ingredients as we are: peas, chickpeas and other legumes. But I don’t know exactly what technology they use.’

‘A lot of innovation in 3D-printing comes from the research field of tissue cultivation: things like printing ears and other organs,’ adds Noort. ‘If you can print an ear, then in theory you can print a piece of meat as well, even though it isn’t edible. We are food technologists who are going to do some 3D printing.

3D printing is a disruptive technology

You can come at this from different angles. I don’t know how scalable their technique is, for example. They are now supplying three top chefs in London, Berlin and Amsterdam. By the kilo. In one of those high-end gastrobars, a piece of meat can cost maybe 15 euros. But in the supermarket, the same piece of meat needs to cost just a couple of euros. I don’t know whether that’s feasible yet. But whatever the case, it is really cool. They have put the flag on the moon, and that’s good news for us too. The first question companies we talk to ask is always: How feasible is it? Now we can say: look, it’s possible already.’

Attention

The burger printer is undoubtedly going to attract a lot of attention. But Noort and his colleagues at Food & Biobased Research have other dishes on their printing menu too. The financing was recently obtained for two big projects in the field of personalized diets.

The consumer demand for more control over our own diet is growing

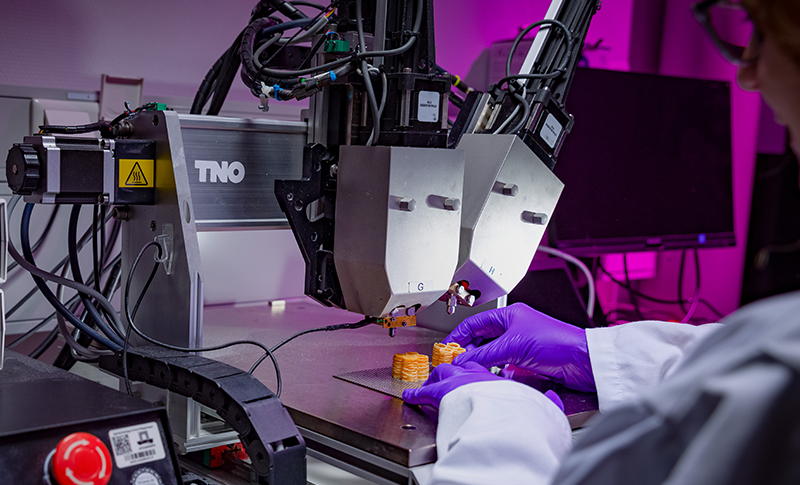

Together with the business world, researchers from WUR, the Netherlands Organization for Applied Scientific Research (TNO) and Eindhoven University of Technology are going to develop a machine that will print tailormade products for the military and for COPD patients. Noort: ‘Wageningen Research is responsible for the food technological and social aspects of the project. Which ingredients should go into the product, how will you do it, how do you ensure you cater for consumer preferences, and what are the requirements for the technology so that the consumer can use it correctly.’

Besides this applied project (Imagine), the Dutch Research Council NWO is funding a fundamental research trajectory (Print Your Food). In this project, WUR and Eindhoven University are developing what is called a digital twin of the print system. This is a calculation model that includes all aspects of the 3D printing process. With that software it is possible to predict whether particular recipes can be printed and will produce an end product with the right structure. A third research area is the processing of waste streams in 3D printers. Noort: ‘The first experiments with that are under way, but it is still in its infancy.’

Joining forces

WUR’s 3D experiments come under the umbrella of the Digital Food Printing Initiative. This collaboration between WUR, Eindhoven University and TNO was launched in 2018 with a view to joining forces. Among the successes is a chocolate printer for Cadbury and a pasta printer for Barilla: two machines that came from the DFPI. Noort: ‘If you want to eat printed pasta in a shape you have thought up yourself, you can order that online from Barilla. It is expensive, but it is possible. TNO collaborated on the chocolate printer, which was recently launched commercially in Australia and India.’

Pasta and chocolate printers don’t change the food world. They are nice little gadgets. A niche. But Noort is convinced that the market for printed food is more than that. ‘The consumer demand for more choice and control over our own diet is growing all the time. That’s not a niche market.

The food world is going to look very different in 10 years’ time

Just look at all the powders sportspeople use, the products for people who don’t want to eat gelatine, chemical additives, gluten, food colouring – you name it. There is ever more diversification. With smart technology and the progress with digitalization, the rate of product development is going to increase rapidly.’

We can’t see any signs of this yet on the supermarket shelves. And according to Noort, whether that is going to happen at all is anyone guess. ‘I’ve been working on 3D printing of food for 12 years now. First at TNO Food and when that went to WUR in 2018, here in Wageningen. Right from the start, the most interesting and intriguing aspect of 3D printing was that it is a disruptive technology. It disrupts the established system. We always compare it with the rise of Über and Airbnb. Who thought up Über? Not the taxi companies. Who thought up Airbnb? Not the Hilton. In the same way, the supermarkets are not behind the development of printed food. Barilla supplies its pasta directly to the consumer, with no involvement of a wholesaler or a supermarket.

Personalized nutrition has no need of the supermarket. The price of processed food as it leaves the factory is currently only a small amount of the price the consumer pays for it. The bigger part goes to the logistical links in the supply chain. They disappear when the consumer is supplied directly. Precisely in these times of Covid and the new way of life it’s bringing with it, there are many opportunities for 3D-printed food. The food world is going to look very different in 10 years’ time.’

YOGHURT

Food printers make a lot of use of processed plant-based polymers as raw materials. The team led by Costas Nikiforidis (of the Biobased Chemistry and Technology Group) takes a different approach and uses emulsions reinforced with pea protein. This discovery got him onto the (back) cover of the latest edition of the leading journal Advanced Functional Materials.

It was not actually his intention to develop printing material, explains Nikiforidis. ‘My team is developing biobased soft materials. The idea of printing with them was really just a bit of scientific fun.’ The researchers first tried to print with a very thick emulsion of oil in water. This kind of emulsion has a fluidity similar to that of mayonnaise, says Nikiforidis. You can print basic shapes with it, but the product soon collapses like a jelly.

That changes spectacularly once you add a type of pea protein. In slightly acid conditions, tiny clumps of protein form which act like a glue holding the closely packed oil droplets together. ‘With the added protein clumps, the printed material has the consistency of a thick tooth paste. And you can eat it. It’s a kind of thick plant-based cream which consists of pea protein, water and oil. They are simple materials, and the process is straightforward and low-energy. In theory you can add any ingredients you like in the oil to create products for special diets.’

PRINTING LESSON

How do you print food? PhD student Yizhou Ma develops software that teaches printers how to print different types of food material. At what speed the material needs to come out of the printer, what pressure it requires, how hot the material needs to be and how fast the platform needs to move under the printer head to get the desired result. Ma: ‘I’m not focussing on any specific printing material but on the control settings on a printer. The aim is that a single printer should be able to print a great many different materials, if you know the right settings. The diversity of foods is very great. That is the big challenge compared with printing non-food such as plastics.’

The settings you need depend on the material being used. Ma uses several cameras to track and record the printing process. ‘A normal camera for measuring the speed of the flow, and a thermal camera to monitor the cooling of the material.’ What he does, in fact, is to calibrate the printer based on the food material and feed the data into software so that the control system can achieve accurate printing jobs across different printers.’

‘The diversity of foods is very great; that is the big challenge.’ Photo: Eric Scholten

‘The diversity of foods is very great; that is the big challenge.’ Photo: Eric Scholten