The guardian of WUR’s treasure trove is retiring. Liesbeth Missel, curator of the Special Collections at the library, leaves a valuable collection of heritage items behind.

The Special Collections department has existed for 41 years, and Liesbeth Missel has been working there for 40 of them. This was her first and only job. And a dream job it was too, for someone who loves books, culture and history. Special Collections is bursting with old botanical books, maps and atlases, garden and landscape designs, botanical and zoological illustrations, prints and photos, some of them aerial. After studying at the Library Academy in Deventer and then qualifying as an archivist in Amsterdam, Missel came to Wageningen in 1981 on the advice of her former teachers. From a temporary job as a librarian at what was then IMAG (agricultural mechanization, RK) she moved on to the Central Library, as it was called then, to work as an assistant at Special Collections. ‘They appointed me on the day the library moved from the building behind the Aula to the Jan Kopshuis (on the Generaal Foulkeweg, now demolished, RK). That move was a unique opportunity to get to know the collection. You handle everything while you are unpacking it all.’

And since then, you and the team have been allowed to collect prize items for WUR’s treasure trove?

‘Yes, you could put it like that. Build it up and make it accessible. Special Collections had been established the year before I came. In 1983, the decision followed to make all the outlying collections part of the Central Library. At one point there were nearly 100 little libraries in Wageningen, some of them run by department secretaries. Collections including maps, and definitely not all part of a library. I started documenting the old editions and maps.’

‘Digitization has done away with the need for adding to collections’

How did the library obtain the rest of the collections?

‘Donations are the main source of the collections, with additional purchases by professors and librarians. Ever since the foundation of the agricultural college in Wageningen at the end of the 19th century, there have been distinguished people who wanted to donate their collections. It started with Staring, one of the founders of that college, who donated part of his library. Later it was mainly collections on garden and landscape architecture that were donated by the descendants of ex-students and teachers.’

Is there an active acquisition policy?

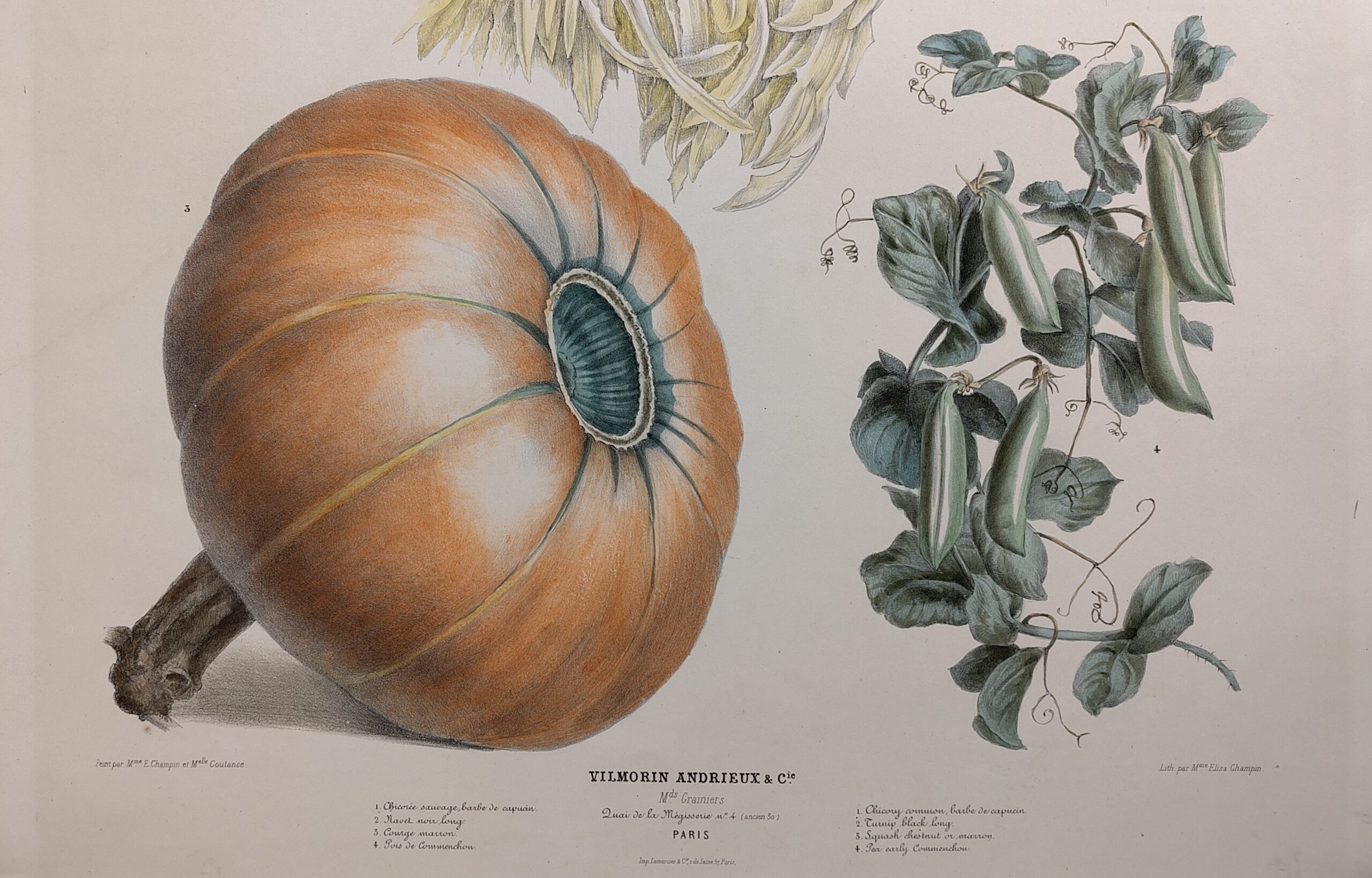

‘There is a policy but not a budget of our own. But if there is something that we ought to have in the collection, it can always be discussed. The point is that, where books are concerned, we are reluctant to buy very much. Digitization has done away with the need to add to collections. You can find a lot online nowadays. Since 2005, the focus has lain on collecting Wageningen academic heritage, which means material from our own organization that came out of, or has been used in, education and research. That is material that we are unique in: drawings, wall displays, nursery and crop catalogues, brochures, photos. We also manage WUR’s art collections.’

Do you have all your material in digital form yourselves?

‘No. For the same reason: some of it is already available digitally elsewhere. Thanks to the Biodiversity Heritage Library, an initiative by botanical libraries around the world, millions of books are available digitally in other collections. And then there is Delpher, Internet Archive, Google Books, and others. It’s a different matter when it come to old maps. They are regularly revised, so it can be difficult to see whether it’s the same. That can make it interesting to digitize them. And we’ve got a lot of collections of old maps.’

Missel has a nice story about how she discovered several old maps in the Surveying building up the hill near the Arboretum. She had gone there to pick up a few books for the collection. ‘In that beautiful room with a view over the water meadows, there were old provincial maps on the wall – with the sun shining on them. I said: those might well be originals. I would love to have them because our Special Collections would be a better place for them. Okay, was the response, but we want to have something on the wall. Right, I said, I’ll come back tomorrow. I had a few facsimiles lying around, things we had duplicates of. When we took the maps out of their frames, my hunch turned out to be right: they dated from 1560-1570. So they were really old maps.’

‘People often have no idea whether something is worth keeping’

The old maps were saved, but other things have been lost over the years. In the move from the town to the campus, attics and cellars were sometimes cleared by people without the relevant knowledge or any sense of history. ‘People often have no idea whether something is worth keeping. It went in the bin, to another institution or to someone’s house. We once got drawings of Indonesian plant pests from someone who had fished them out of the bin at a department. There was once a zoological museum at Duivendaal. There is a list from 1894 of models of animals, plants, body parts and organs from that museum. The Auzoux horse, now at the entrance to the library, comes from that collection. Recently the model of a sheep’s stomach came to light. We have no idea what happened to the rest.’

Is WUR proud enough of its own heritage, then?

‘There is room for improvement, though it varies per institution. Academics from Delft, for example, are much prouder of who they are and the instruments they have developed. Of course, architecture is very tangible. In Wageningen, the knowledge goes more into a production method or a system, which is less tangible. That is reflected in the way we celebrated our centenary too. The focus was not on what we have achieved, on our history, but on what we are now and what we can do. To some extent that’s a pity because it means knowledge gets lost. The Edelman auger for soil sampling is still famous, for example, but hardly anyone has heard of the Dieperink beacon, a land-surveying instrument. We’ve even got a patent on it.’

The Special Collections are not exactly highly visible. Will that change?

‘Yes, that is a pity. The latest idea is to create smaller exhibitions in various buildings, with material relevant to the building. That was before Covid broke out.’ And the portraits of rectors now hanging up in the Aula are going to be put up in the new Dialogue Centre. As will a number of plaques relating to the history of the university. We have also thought about installing a kind of touchscreen tabletop with which you can exhibit the collection digitally. But I don’t know if that will happen.’

Wat moet er nog meer gebeuren om Speciale Collecties zichtbaarder te maken?

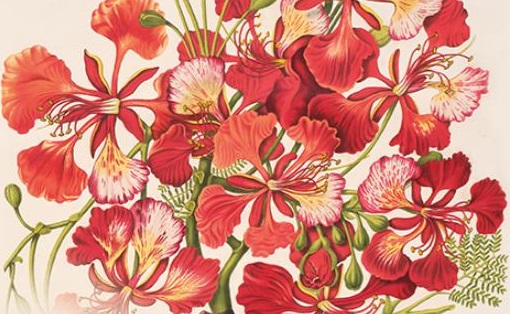

My successor Anneke Groen will work on the visibility of the collections. We are keen for the history of science to play a bigger role. For us to make WUR stories more visible. As an example: part of the Krelage library was once given to us as a donation. The rest was auctioned. I recently bought a catalogue of that auction. Krelage was one of the big traders in flower bulbs, who put the Netherlands on the map as the land of bulbs. He got an honorary doctorate from Wageningen. I would like to write a story about that collection. And of course, it would also be nice if we had a kind of university museum that links our history with the present and the future. It wouldn’t have to be a classical museum; it could be digital.’

Missel’s personal Top 3 from the collection

- ‘An art book by Simon Schijnvoet, a landscape architect and print artist who lived in the 17th and 18th centuries. It is an album in which he kept his own work as well as drawings by other people, such as Alida Withoos. I studied history as a mature student and wrote my thesis about her.’

- ‘A first edition of Darwin’s book The Different Forms of Flowers on Plants of the Same Species, from 1877. It was a publisher’s copy sent to the Swiss professor Nägel. The address, in Darwin’s handwriting, is stuck into the back of the book.’

- ‘The Tulips book by the florist P. Cos, from 1637. Indisputably the crowning glory of our collection. A book of international stature, and a frequent loan request for exhibitions. The book was purchased from the Krelage collection.’

Photo: Guy Ackermans

Photo: Guy Ackermans