The Netherlands is suffering a nitrogen crisis. Tough measures such as reducing the national livestock herd seem unavoidable. So what do international BSc, MSc and PhD students think about this problem? Does it exist in their countries too?

Text: Coretta Jongeling en Roelof Kleis

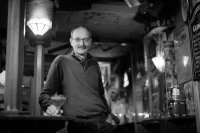

Professor of Plant Production Systems, from the UK

‘I think it’s a shame it took a court case to get the problem tackled. The nitrogen problem was flagged up by scientists, including people at Wageningen, a long time ago. I support the idea the agriculture must be efficient, but that efficiency has led to serious damage to the environment. Lowering the speed limit on the motorways is not enough. And I don’t have much faith in technical options for cutting ammonia emissions. The nitrogen will just end up in the environment in a different form. In English that’s called pollution swapping. The heart of the matter is that too much nitrogen is imported. In the end we shall have to move towards importing less livestock feed. And the environmental costs must be calculated into the cost of our food. In general we shall have to start paying more for our products.’

An MSc student of Animal Sciences, from Germany

‘In Germany, we are still busy with our own version of the nitrogen issue. Most successes in nitrogen reduction there were the result of improvements in the sectors of transport and wastewater treatment, not livestock. Two of the proposed solutions to the Dutch crisis that I have heard of are to either halve livestock numbers or house cattle in closed, air-filtered sheds. When it comes to Dutch farming, public opinion in Germany is generally positive, especially regarding livestock welfare. A lot of our own dairy cattle are still kept tethered, a quarter of them year-round, without access to pasture. Personally, I would hate to see the Netherlands turn to this form of livestock housing. I have no answers to this problem, but as the sector caters to the demand of a system we created, my own solution is to minimize meat and dairy consumption.’

PhD in Animal Production Systems, from Peru

‘In my country we don’t have limits on nitrogen emissions. Most of our food is produced by smallholder farmers and many of them can’t afford fertilizers. We have got other environmental problems like deforestation, overfishing and water pollution because of illegal gold mining. The density of the animal husbandry in the Netherlands is huge. But halving the number of animals won’t solve the problem. If people go on consuming animal products at the same levels, which are very high, these will be produced somewhere else. And so will the nitrogen. The nitrogen crisis is a societal problem. Dutch people should not only reduce their speed on the highways, but also reduce the quantity of animal products in their diets. It’s not fair just to point the finger at the farmers. I do think it is true, though, that reducing animal numbers is part of the solution. It’s just not the only one. There have to be systems for compensation too, so farmers can switch to a more sustainable systems. One in which consumers are be willing to pay fair prices – that would be ideal.’

Animal Nutrition postdoc, from Canada

‘The biggest difference between Canada and the Netherlands is the intensity of the farming. If you keep a lot of animals in a small area many problems soon get much worse. It’s far too simplistic to say we need to half the number of animals. Feeding dairy cows is what I have most experience with, and there are already several ways we can change the industry without necessarily reducing the number of animals. I guess that’s the same for pigs and poultry. A few small changes could make huge difference. The number one thing for dairy cows would be reducing crude protein levels in their diet. There is far too much nitrogen in Dutch feeds, to ensure high milk production. But our research has shown that you don’t need to do that.’

MSc student of Organic Agriculture, from France

‘Nitrogen is not as big a problem in France as it is here. There is more discussion there about the use of pesticides. Less intensive agriculture would be a good solution, meaning keeping fewer animals in better living conditions. Consumers should then be prepared to eat less meat, and you need good information campaigns to achieve that. It would be better anyway if people invested in better quality products that last longer. It is strange that the Netherlands exports a lot of meat and imports so much other food. Emissions would drop massively if there was less transportation of livestock, but that would take political change.’

Landscape Architecture and Spatial Planning researcher, from Switzerland

‘Farmers in Switzerland have to keep records of their nitrogen emissions, but there is not much discussion about that. And there is no external pressure, since Switzerland is not in the EU. The use of pesticides is a subject of public concern and discussion, though. My PhD is about the politics of nitrogen reduction, so I’m finding the discussion in the Netherlands very interesting. The nitrogen problem is very complicated and I think the solution lies in a combination of different things. Technical solutions are not enough, and I think the spatial dimension of the problem is very important. For the sake of biodiversity, we need areas where there is zero nitrogen input. My chair group is thinking through the option of smart, innovative intensification in one place and switching to extensive farming elsewhere. Another question is how much agriculture is possible in the Netherlands. For a real solution, social change is required.’

Illustration: Henk van Ruitenbeek

Illustration: Henk van Ruitenbeek