Poultry farmers have an extra reason to plant trees on their land: their chickens are happier in the shade.

Series: Experimenting for the climate

The Netherlands aims to cut its greenhouse gas emissions by 49 per cent by 2030, compared with 1990. How we are going to do that is to be laid down in a comprehensive Climate Agreement. But while the politicians in The Hague haggle over the contents of that agreement, around the country numerous experiments in emission reduction are already under way. WUR is coordinating all the pilot projects for the Agriculture and Land Use sector. Resource will be taking a look at these experiments in the next four numbers. This week, episode 2: Forestry.

On Johan, Jantine and Ariën Verbeek’s organic poultry farm outside Renswoude, 201 walnut trees have been planted. They are now just lean saplings barely two metres in height, planted about ten metres apart. You could hardly call it a wood yet, but in another few years it will be a pleasant, shady spot.

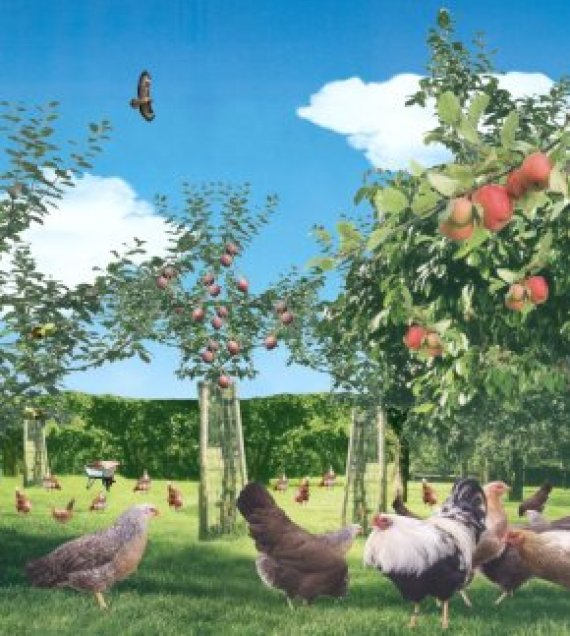

The walnut orchard will be the outdoor run for some of Verbeek’s 16,000 organic chickens. The new group has just arrived and is still acclimatizing in the barn. Once the chickens have adjusted, they will start using this wooded plot as their outdoor run. The project is one of several WUR-led pilots that aim to demonstrate how additional forestry interventions can contribute to the battle against climate change.

Agro-Forestry

The trial on Verbeek’s land is an example of agroforestry, which project leader Martijn Boosten defines as: ‘a combination of agriculture and forestry that creates a win-win situation.’ Boosten works for the Wageningen-based NGO Probos. ‘In this case, that is combining poultry farming with planting new trees.’

Birds of prey are a problem here: hawks and buzzards

Chickens were originally Asian forest animals and still have a preference for the forest lodged deep in their brains, says farmer Johan Verbeek. ‘I’ve got a big shed over there with a wood alongside it. If there’s any threat of danger, the chickens fly into the woods.’ And danger is always hovering. ‘Birds of prey are a problem here: hawks and buzzards.’

The legal requirement for organic or free-range chickens is that they each have four square metres of outdoor space, says Boosten. ‘But in practice you can see that they don’t use all that space, by any means. Chickens tend to keep close to the barn, which offers them shelter and safety. By planting trees in the outdoor area, you attract the chickens into it. That is good for the chickens and you are capturing CO2.’ Boosten points out a few more advantages of the concept. Less disease, for instance, because they chickens are less crowded together if they make better use of their outdoor space. Trees make the farm more attractive too, and they are productive in the long run. These particular trees will produce walnuts.

Keep it simpel

Planting trees in the chicken run is not a new idea. Both Probos and the Louis Bolk Institute have prior experience of planting fruit trees, willows and elephant grass. One of those pilots was done on the Verbeek farm too. Right in front of the farmhouse there are dozens of apple, pear, cherry and plum trees on a two-hectare chicken run. That was a steep learning curve, recalls Verbeek. And the main lesson was: stick to what you know about. ‘Maintaining fruit trees calls for specific knowledge. And it was not so handy to opt for four different kinds of fruit trees. We are not fruit farmers.’

‘Growing fruit trees requires expertise and money,’ confirms Boosten of Probis. ‘Planting one hectare easily means an investment of 20,000 euros. In a good year, you recoup that, but then you become a fruit farmer of sorts, really.’

So the message is: keep it simple. That is why three out of the four farmers carrying out a pilot with supervision from Probos opted for walnut trees, which are relatively cheap and low-maintenance. The fourth chicken farmers wants to plant willows to produce biomass.

Benefits

Planting the trees cost Verbeek 12,500 euros, not counting a subsidy that covered one quarter of the costs. So that investment has to be recouped. ‘That is the idea behind these pilots,’ says Boosten. ‘Show the costs and the benefits. Projects like these have to be able to cover their costs in the end. They are not supposed to keep going on subsidies endlessly.’

Agroforestry projects like this one have to cover their own costs in the end

But for the time being, the benefits side of things is a long-term affair. It will take six years before the walnut trees bear any fruit, estimates Boosten. ‘Ten years even, for a reasonable quantity to sell.’ Seeing will be believing for Verbeek, when it comes to profits from sales. In fact, those walnuts could cause problems. Germany is an important export country for Verbeek’s organic eggs. Verbeek: ‘But the German certifying agency KAT has said it won’t accept eggs from a farm where the outdoor run is used for two economic purposes. Like eggs and walnuts. Strange, yes. It’s OK for me to give the walnuts away or feed them to my pigs, but not to sell them.’

Klimate eggs

It remains to be seen how this will work out. Meanwhile Verbeek sees more future in selling his agroforestry eggs as a niche product. Verbeek is chair of the cooperative Biomeerwaarde-ei, a group of organic farmers who want to be more ambitious about sustainability. Verbeek thinks the added value of his eggs lies in things like the use of solar panels on the farm. The green chicken run adds sustainability value too. ‘We can get a better market position for the ‘organic added value egg’ like this.’ Will that lead to a new egg on the supermarket shelf, the climate egg? Verbeek savours the word approvingly. ‘That’s quite possible.’

Reducing emissions with better forestry

Greenhouse gas emissions can be reduced significantly by planting additional trees or managing existing forests better. WUR and 33 partners are conducting a serious of pilots to map out the possibilities. The forestry projects cost a total of 2 million euros, a small proportion of the 19 million WUR received for all the pilots in the Agriculture and Land Use sector under the Dutch Climate Agreement. The information from all the pilots will provide a toolbox that land managers can make use of.

The pilots are all about carbon sequestration, says coordinator Gert-Jan Nabuurs (professor of European Forests), and are in line with the idea of Climate-smart Forest Management launched at the climate summit in Paris in 2015. Besides wooded chicken runs, the concept includes such things as creating food forests, planting new forests with tiny houses, and climate-smarter management of existing forest. Nabuurs has the highest expectations of the latter. ‘In the Netherlands there is a lot of older forest where little has been invested in rejuvenation. The biodiversity is often negligible too.’ With rejuvenation and filling open spaces, you can revitalize such forests, says Nabuurs. Expanding it with new areas can also make a big difference. ‘Provinces still have to lay down some of the Nature Network (formerly known as the Ecological Main Structure, ed.). Planting trees can play a role in that if you look for smart combinations with things like water storage, urban expansion or increasing biodiversity.’