Extension cables dozens of metres long for exam rooms, microscope light filters or parts for synthetic meat machines: the Wageningen Technical Solutions workshop makes whatever researchers need but aren’t able to buy anywhere. Including a special placemat to go under a tray for nutritional research, named after Taylor Swift.

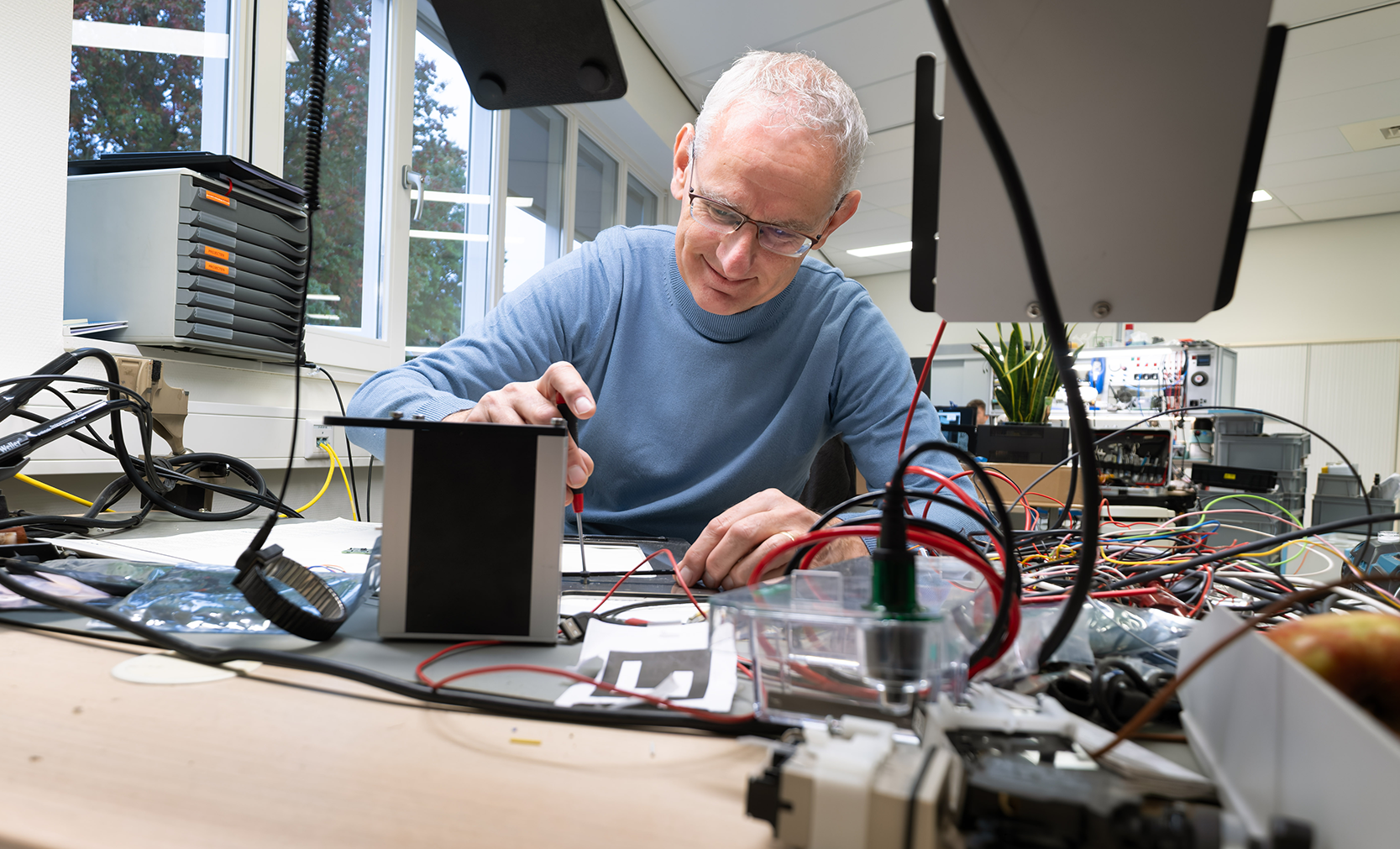

Hans Meijer has been working in the university workshop for more than 30 years. He started out as an expert in electronics and technical automation, but these days his skills extend to 3D printing and cutting plastics with lasers. ‘We work for the research and education sides of WUR, making all the things you can’t buy,’ he says as he picks up a thin, silvery rectangle from his desk. It is the third version of the ‘smart tray’, something he developed with the client, Human Nutrition & Health lecturer Guido Camps. This clever piece of tech is used in nutritional research. You put it underneath a tray, like a placemat, and it lets you measure how test subjects eat and how much — accurate to the nearest gram.

The metal mat Meijer is showing as an example of his work is completely different to the first version he made in 2018. In that model, the sensors were embedded in the tray itself rather than in the placemat. ‘The sensors in the tray had to be very thin,’ recalls Meijer. ‘Normal sensors for scales didn’t fit. We found what we needed from specialized force sensor manufacturers. The smart tray had three circular compartments and each compartment needed three weighing sensors, so we needed almost 30 for the three trays we were making. When we ordered the sensors, we had to answer all kinds of complicated questions because the sensors can also be used in weapons systems. I had to prove we weren’t building rockets.’

Dishwasher

The smart tray has undergone a substantial transformation. The research dieticians, who use it a lot, didn’t like the fact that it couldn’t be put in the dishwasher. Camps and Meijer discussed possible solutions and came up with a smart placemat that you put the tray on. Meijer: ‘It’s much more user-friendly because now you can mess up the tray, as it goes in the dishwasher, but the mat underneath doesn’t get dirty.’

Sometimes equipment gets so old that the suppliers no longer provide spare parts, so we make them.

In the transformation from smart tray to smart placemat, another technological issue arose that Camps’ PhD candidate Florian Walter is now working on. Camps: ‘The tray rests on the weight sensors. For accurate weight measurements, you need three points of contact, forming a triangle, to prevent potential wobbling. When the switch was made from the tray to a placemat underneath it, calculations showed that the mat had to be one metre by 50 centimetres to include all the sensors.’ That’s impractical – it wouldn’t even fit on a normal dinner table. Now they work with four sensors in a mat measuring about 50 by 30 centimetres. Walter: ‘The fact that it’s rectangular introduces calibration challenges, though – for example caused by wobbling, because plastic trays warp easily and are then no longer properly in contact with all four weight sensors. That’s the problem I’m now trying to solve.’

Trial and error

The workshop staff are always making things that don’t yet exist, so it’s not surprising they don’t always get it perfect. ‘For example, you realize afterwards another approach would have been much easier, or you would have made different choices with hindsight,’ explains Meijer. Camps agrees. He is now working on the third generation of his smart measuring instrument.

After the initial version in 2018, Meijer, Camps and his PhD candidates continued making both minor and major modifications to improve the device. The first version sent the data to a server, but today’s faster processors mean that the current model can store all the data on its local minicomputer. The mat is made from aluminium and stainless steel, which is tougher and more stable than the original plastic tray. That means less noise in the data collected by the device.

All the teething troubles seem to have resolved now and the current mat looks to be a lasting solution. Camps: ‘The series of mats we have now is modular so we can continue adapting and repairing them. We have 16 mats at present. Initially, we gave each one a number but the PhD candidates in my group recently organized a competition to name them. That resulted for example in TRAYlor Swift.’

Repairs

Meijer and his colleagues in the workshop don’t only make new instruments, they also keep old equipment alive. ‘Sometimes equipment gets so old that the suppliers no longer provide spare parts. That happened for example with a special grinder. It worked fine except for that one part. It would have been a shame to have to throw it away and buy a new one, especially now the university has to be so careful with its costs. We designed a new part and printed it on the 3D printer, and now the grinder is as good as new.’

When asked whether they can really make absolutely anything, Meijer replies: ‘Yes, except for glass instruments. WUR used to have its own glassworks where they made the glassware for the practicals, among other things. But we no longer have people with that knowledge and those skills. We can still cut glass sheets and we have contact details for a glassworks that we collaborate with regularly.’

‘New’ location

The workshop officially reopened on campus at the start of October. Until last summer, WUR had two workshops: the Technical Development Studio for Agrotechnology & Food Science and Tupola for the Plant Sciences people. The two merged and moved into shared accommodation in Innovatron following some major renovations.

Hans Meijer in the Wageningen Technical Solutions workshop in Innovatron. Photo Guy Ackermans.

Hans Meijer in the Wageningen Technical Solutions workshop in Innovatron. Photo Guy Ackermans.