Ingrid Luijkx performs highly accurate measurements of oxygen levels in the air. That signal reveals how much of the emitted CO₂ remains in the atmosphere.

The amount of CO₂ in the atmosphere is continually rising. The increase last year was abnormally large. Scientists think that might be because forests are absorbing less CO₂ from the air. Ingrid Luijkx, an associate professor of Meteorology and Air Quality, is conducting research to get more certainty about this. She is using the oxygen concentration in the air to obtain a clearer picture of emissions and uptake of CO₂.

Emissions due to fossil fuels are continually increasing the amount of CO₂ in the atmosphere. About half of what is currently being emitted remains in the air. The other half is absorbed by the oceans and the forests in roughly equal proportions. ‘But that uptake can fluctuate depending on the conditions,’ says Luijkx. ‘Forests absorb less CO₂ in very dry years, and oceans also absorb less as they become warmer. If you want to know how climate change is going to alter the amount of CO₂ in the atmosphere and make predictions, you need to figure out what effect all the underlying processes have.’

Fingerprint

The extra information that is needed for this is provided by oxygen. Luijkx: ‘Oxygen measurements let you distinguish between fossil fuel combustion and the uptake by the biosphere.’ Oxygen plays a key role because it is involved in both combustion (the formation of CO₂) and photosynthesis (the sequestration of CO₂). According to Luijkx, oxygen provides a kind of fingerprint of the CO₂ level in the atmosphere.

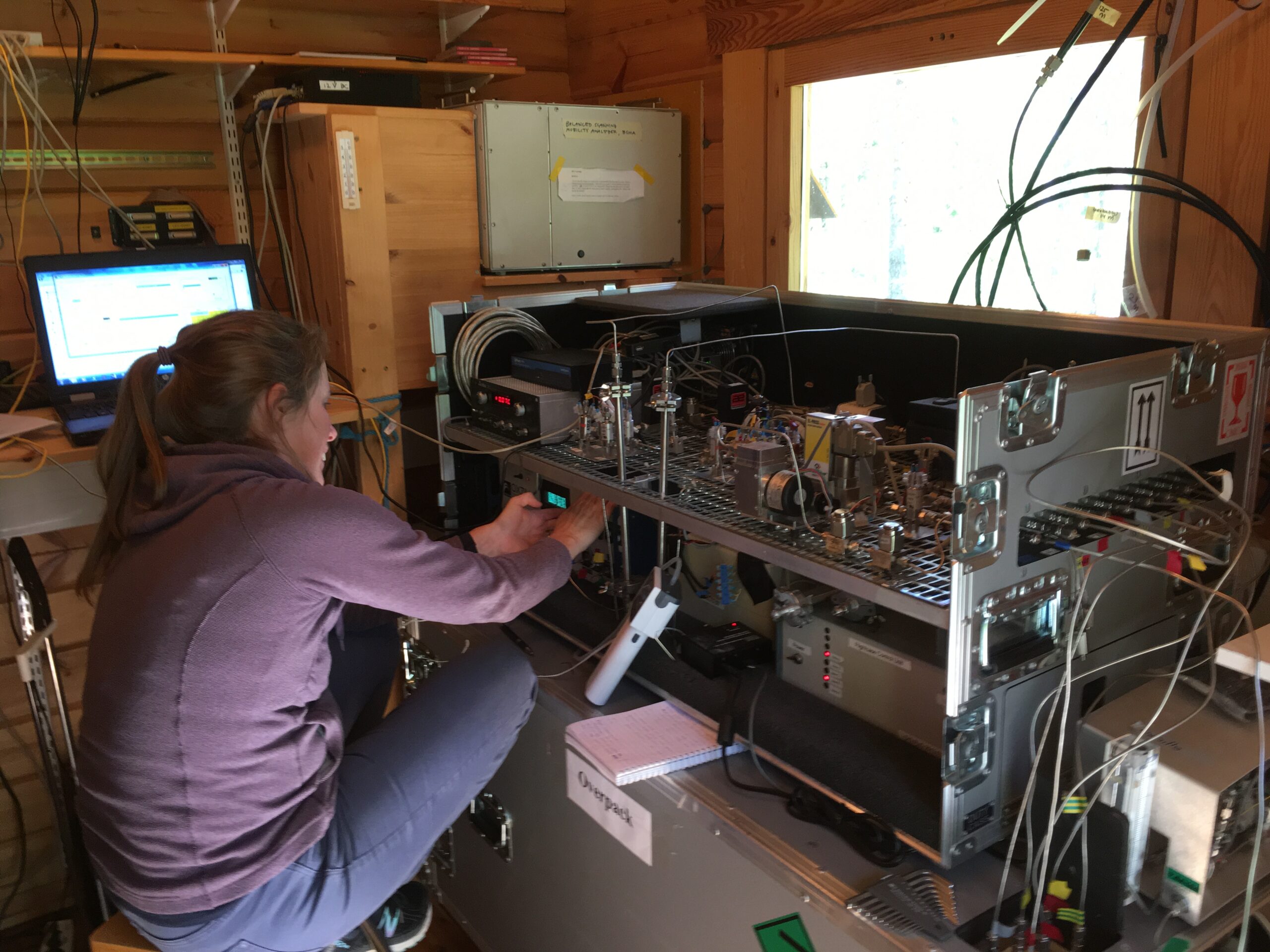

But that requires you to be able to make very precise measurements of small changes in the oxygen level, which is far from easy. Oxygen is present in abundance in the atmosphere, making up 21 per cent of the air. Try measuring a few extra molecules in that enormous amount of oxygen. But that is precisely what Luijkx does, using a device she developed herself during her PhD in Groningen, 15 years ago. She was the first person in the Netherlands to do this kind of measurement.

Lead

Luijkx studied physics in Groningen. ‘I combined technical physics with environmental physics, with a focus on environmental issues. That was how I ended up doing atmospheric research.’ For her PhD, she studied the exchange of carbon dioxide and oxygen above the North Sea. The oxygen meter she built to do this is essentially quite simple, she explains. ‘It’s a fuel cell in which a current is generated if you let air flow through it. That is because the oxygen reacts with lead. It’s basically the same process as in a battery that provides electricity. The more oxygen in the air, the stronger the current.’

The pandemic was a kind of real-life experiment

You can buy these oxygen meters off the shelf, but you need a lot of peripheral equipment to get the accuracy needed to measure atmospheric signals. Luijkx developed the concept and put together a prototype. The ‘flight case’, as the device is called, is the same size as a large freezer. The name refers to the aluminium casing, which is similar to the freight containers used on planes. There are now two newer versions in operation: one carries out measurements on the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI) mast at the Cabauw station in Utrecht; the other is in Groningen.

Pandemic

After her doctorate, Luijkx moved to Switzerland for two years as a postdoc. She carried out oxygen measurements at an altitude of 3500 metres on the Jungfraujoch glacier near Interlaken. Then she switched to Wageningen. Here, she got the opportunity to master the art of modelling atmospheric processes. ‘Performing measurements in one specific place is interesting, but it doesn’t tell you much about the climate problem or give you the bigger picture of CO₂ on the global scale.’ She has been working on that bigger picture ever since. And making a name for herself too. She has already secured a Veni grant, a Vidi grant and EU funding for her research.

That her method gets results became clear in 2022. Together with British colleagues, Luijkx demonstrated that CO₂ emissions fell by almost a quarter during the pandemic in the UK. ‘You couldn’t see that decrease just by looking at the CO₂ signal, because the signal depends a lot on the amount of CO₂ absorbed by the biosphere. The decrease that was calculated based on energy consumption was 17 per cent. We got a decrease of 23 per cent based on our oxygen measurements, so that is pretty close. The pandemic was actually a kind of real-life experiment.’

For her Veni project, Luijkx set up her equipment in the forests of Hyytiälä in Finland. Measurements were performed at various heights above the forest to get a better understanding of the net outcome from CO₂ uptake by forests. ‘The net value depends on two processes: photosynthesis (uptake of CO₂ by plants) and respiration (emissions by the vegetation and from the soil). But atmospheric processes also influence the concentrations. You need to be able to distinguish those processes to interpret the measurements correctly. On 8 July, Kim Faassen will get her doctorate for the development of a fundamental framework for this, based on those measurements.’

Since September, oxygen measurements have been made from the transmission mast at Cabauw, Utrecht, with funding from the EU CORS project and the Vidi grant. ‘This year, I hope to set up a similar measurement system at De Zweth station near Rotterdam. That will let us build up a good time series for the Netherlands.’

Multipurpose

Oxygen measurements using Ingrid Luijkx’s method have recently started for individual leaves. This is a study she is doing with researchers at Plant Sciences. The exchange of carbon dioxide and oxygen under varying conditions tells us more about how photosynthesis and respiration depend on factors such as temperature and the amount of light. ‘It’s funny to see how you can use the same measuring equipment for completely different purposes,’ says Luijkx. ‘We want to know more about the atmosphere while they want to improve photosynthesis models. It’s great you can start up collaborations like this so easily in Wageningen.’

A lot of peripheral equipment is needed to measure oxygen accurately. Ingrid Luijkx designed this device herself and used it to perform measurements in a Finnish forest. Own photo.

A lot of peripheral equipment is needed to measure oxygen accurately. Ingrid Luijkx designed this device herself and used it to perform measurements in a Finnish forest. Own photo.