The discussion about the dangers of gene editing using CRISPR-Cas has died down, but the question of who will gain financially from the method is still very much alive. Microbiologist John van der Oost is making every effort to ensure gene editing benefits people, society and the environment.

‘Evolution is the result of genetic modification, as all biologists know,’ says microbiologist John van der Oost (1958). ‘Given that, I felt that the whole debate about the safety of CRISPR-Cas techniques and the need to label products was very overblown. We all eat tomatoes, which evolved from a wild tomato that has undergone changes in about 15 million of its billion base pairs over thousands of years of plant breeding and mutagenesis. They are seen as safe, but plant geneticists say you could now get more or less the same result using CRISPR-Cas to perform six knock-outs in one of those wild tomatoes, only changing 15 base pairs. And that tomato is supposed to be risky. I don’t accept that at all.’ On 21 March, Van der Oost received the M.W. Beijerinck Virology Prize, worth 35,000 euros, for his pioneering work on the CRISPR-Cas technology. On 27 June, he will give his farewell lecture and a symposium in Wageningen, exactly 30 years after he was appointed head of the bacterial genetics group.

Patiently

According to Van der Oost, the discussion about the dangers of CRISPR-Cas faded out thanks to the provision of consistent information and to technical improvements. ‘There were concerns with Cas9 at first because of unintended off-target effects, but that problem was resolved by making changes to the guide RNA, and the efficiency was improved in Cas12,’ says Van der Oost. ‘Over the past few years, I’ve given talks in pretty much every venue in the Netherlands and each time I have patiently explained this.’ Meanwhile, CRISPR-Cas gene editing has been embraced in almost every field of research, with more and more successful applications. ‘Take the ten patients with hereditary angioedema (a swelling disorder) who, according to a report from Amsterdam UMC hospital last year, have been permanently relieved of their complaints following a single CRISPR-Cas transfusion,’ says Van der Oost. ‘Or the research published last week in which American doctors cured a baby with a rare metabolic disorder by using CRISPR-Cas to make a precise correction to the mutation in the liver cells. People are now fine-tuning CRISPR-Cas and gene editing has become the future.’

Patents

‘However, specific applications are still very expensive and you have to navigate a minefield of patents. The question of who is going to earn money from this is still very much alive,’ admits Van der Oost. He himself is working on his 40th patent. One of his first patents on Cas12 was included in a portfolio of patents from MIT’s Broad Institute in Boston, the work of biochemist and fellow CRISPR-Cas pioneer Feng Zhang. That institute also has basic patents on medical applications of Cas9, which are still being challenged in court by UC Berkeley and biochemist and Nobel Prize winner Jennifer Doudna. ‘Applying for a patent is little more than speculation,’ says Van der Oost. ‘Personally, I’m towards the left of the political spectrum and I’m not keen on commercial models and not remotely interested in Monsanto-like monopolies.’ He also thinks the idea of using CRISPR-Cas — possibly even one of ‘his’ patents — to revive the extinct dire wolf or the mammoth is a load of rubbish. ‘I subscribe to the Norwegian model that says gene editing is only permissible if it is safe and beneficial for people, society and the environment. That is why we decided in 2021 to grant licences for five of our Thermo-Cas9 patents free of charge to non-profit NGOs that aim to improve the global supply of food.’

We made an important contribution to knowledge development and I don’t regret a thing

‘That idea came to me when I was watching a TV report in which my WUR colleague, the plant physiologist Christa Testerink, talked about her research on salt-tolerant and drought-resistant crops in partnership with the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines,’ explains Van der Oost. ‘We are now working together in the SurpRICE project on a stable Thermo-Cas9 system, which students here isolated from a thermophile bacterium in a compost heap. We are combining knowledge about thale cress, the tomato and rice to optimize our Thermo-Cas9 for the genetic modification of rice to let the crop cope better with salinization and drought. We have already made significant progress and hopefully we will get enough room for manoeuvre in terms of patents and approvals to launch these new rice varieties on the market along with the IRRI.’

Vici

Now he is so close to retiring, Van der Oost looks back on his career with satisfaction. The high point was the Science publication in 2008 — together with microbiologist Stan Brouns, now at Delft University of Technology, and the American genome biologist Eugene Koonin — on the Cascade complex and the Cas3 gene in E. coli. ‘That was the first publication to show convincingly how prokaryotes defend themselves against viruses by using the CRISPR archive and cutting pieces out of the virus genome. We were also the first to create a designer CRISPR, three years before others showed how that lets you edit programmable genomes. We made an important contribution to knowledge development and I don’t regret a thing.’ Looking back, he is grateful to the Dutch Research Council and his boss at the time, the microbiologist Willem de Vos, for giving him the freedom to use the Vici grant he received in 2004 for a very different purpose. ‘After Koonin pointed out to us that our E. coli contained CRISPR genes, I decided to focus my research entirely on that aspect. In retrospect that was a crucial fork in the road. I’m glad I took the right turning.’

Text: Bionieuws/Gert van Maanen

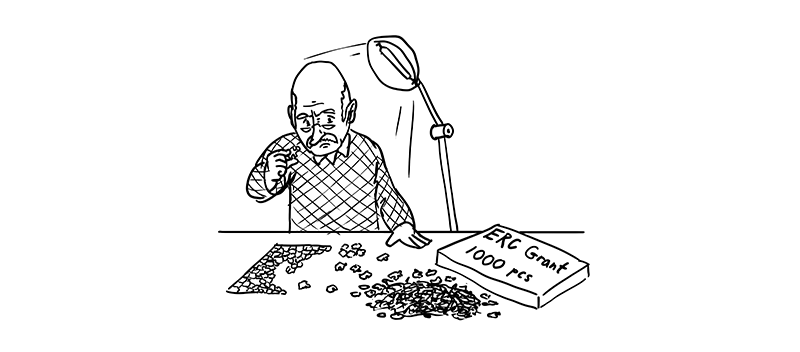

John van der Oost (in checked shirt) during a Resource debate about CRISPR-Cas. Photo Aldo Alessi

John van der Oost (in checked shirt) during a Resource debate about CRISPR-Cas. Photo Aldo Alessi