Self-funded PhD student Mitchell Harker (Human Nutrition & Health) studied the mid to long-term effects of the bariatric SADI-S intervention, through which patients with obesity undergo both a gastric sleeve and a gastric bypass. ‘Little is known about the results after five years.’

Harker is a doctor and researcher at Vitalys, Rijstate Hospital’s clinic for overweight, and is pursuing his PhD at WUR on improving surgical methods in the treatment of overweight. He studied the differences between secondary and primary SADI-S for his most recent publication, focusing on a gastric sleeve followed by a gastric bypass, or both procedures performed simultaneously. He followed a group of patients for five years.

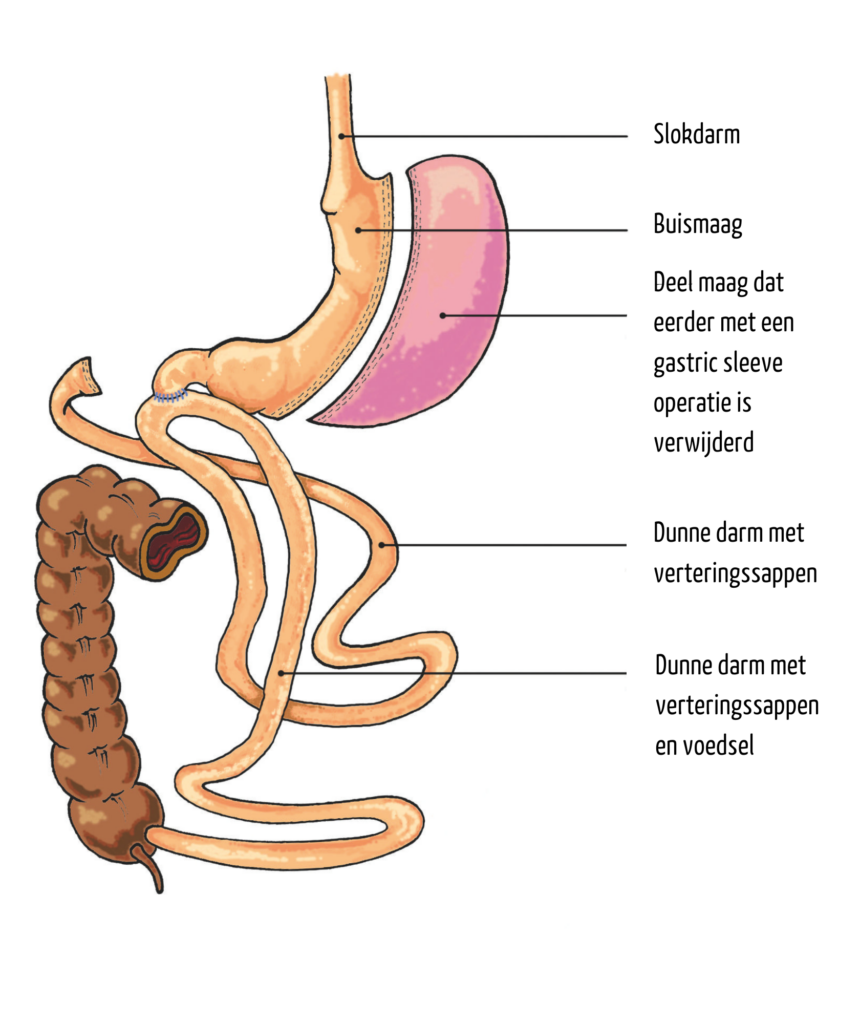

This is an intervention for patients with severe overweight, to double the effect in terms of weight loss, Harker explains. ‘We reduce the size of the stomach by about 80 per cent, to the size of an average pear or an elongated grape, as well as moving the entry point of the stomach into the small intestine. This causes patients to feel satiated sooner, and absorb fewer nutrients and calories from their food intake because a considerable portion of their small intestine is bypassed.’

One versus two

‘The advantage of two separate procedures is that patients lose a considerable amount of weight after the first intervention, reducing the amount of abdominal fat and fat surrounding the liver, which otherwise obstructs the view and access to the stomach and intestine, Harker explains. Once that is gone, it is easier for a surgeon to reattach the stomach to the intestines for the bypass, ‘preventing complications.’

On the other hand, patients who undergo the SADI-S in two separate sessions lose less weight over a five-year period. ’16 per cent of their total body mass, as opposed to 35 per cent in patients who have both procedures carried out simultaneously.’ It must, however, be noted that the latter suffer more complications, which sometimes make additional surgery necessary. Harker: ‘That begs the question: is the extra weight loss worth the risks?’

Residual intestine

Harker and his colleagues also studied different spots for the new entry point of the stomach into the small intestine, and the consequences of a shorter or longer piece of intestine with its original function. ‘Surgeons cut the stomach loose and reattach it further down the intestine. Digestion-enhancing substances produced by the pancreas flow through the part of the intestine that is located before the point of attachment, where the stomach contents are added and digestion takes place as normal. The length of this last part, which operates as it did prior to the surgeries, is relevant.’

Is the extra weight loss worth the risks?

Mitchell Harker, researcher, medical doctor and self-funded PhD student

This residual length must be short enough to ensure fewer nutrients are absorbed to ensure weight loss. However, not too short, as ‘this could cause patients to suffer from vitamin deficiencies and experience symptoms of malnutrition. In the most severe cases, they would have to be given IV or tube feeding for the rest of their lives. Literature shows us that a length of less than two-and-a-half metres barely results in additional weight loss, while increasing the risk of deficiencies.’

Quality of life

The SADI-S procedure also alters the patients’ bowel movements. ‘We shorten the gastrointestinal tract, which means food is no longer fully digested. As a result, patients typically experience approximately four bowel movements per day, producing a thin stool. One in five patients report this hinders them in their daily life.’

Harker surveyed patients on their quality of life approximately three years after their last operation. ‘All patients reported that their quality of life was acceptable, although it was higher among patients who underwent primary SADI-S. We believe this is due to the fact that the other group, which underwent the secondary SADI-S, started earlier, hence their weight loss started earlier.’

The result is still important, Harker states. ‘Very little research has been done on the quality of life among patients who underwent gastric surgery. Weight loss is often the most important outcome, which is logical from a clinical perspective, because it improves the patients’ health. But acknowledging the patient’s experience is also important.’

A gastric sleeve reduces the size of the stomach by approximately 80 per cent, to the size of an average pear or an elongated grape.

A gastric sleeve reduces the size of the stomach by approximately 80 per cent, to the size of an average pear or an elongated grape.