Thus discovered master’s student Noor Appelman. She published the discovery from her thesis in a scientific journal.

If you put droplets of oil in water, they start ‘dancing’ spontaneously. This is what student Noor Appelman (MSc Molecular Life Sciences) and assistant professor Siddharth Deshpande of Physical Chemistry and Soft Matter discovered. ‘The droplets together do something very different than you would expect based on a single droplet,’ says Deshpande. ‘It is a so-called emergent phenomenon. We normally see this in complex biological systems like a swarm of starlings or a school of fish, but our research shows it can also happen in simple, non-living systems.’

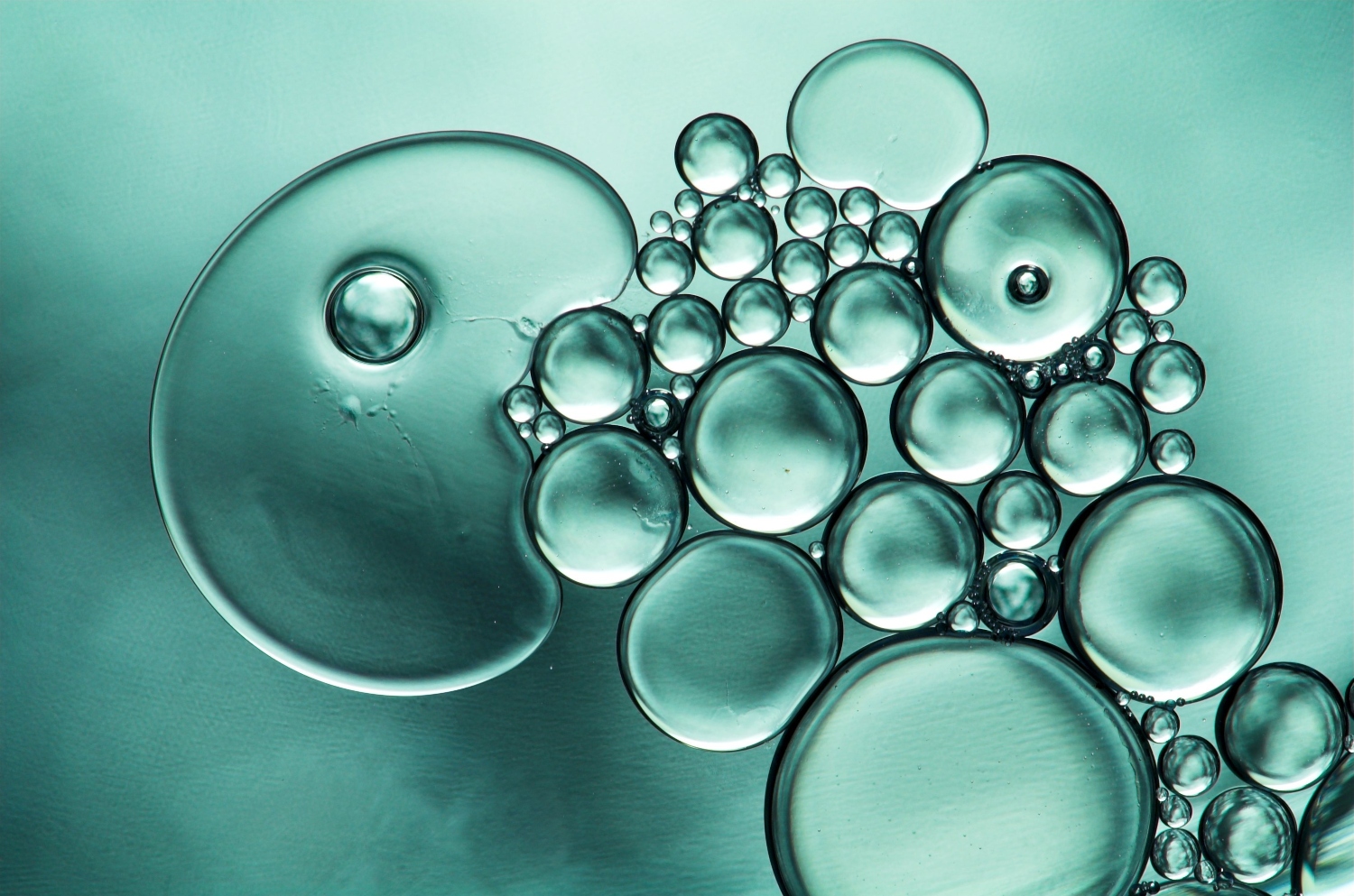

Such emergent behaviour of droplets was already known from non-living systems with three ingredients, but Appelman and Deshpande now succeeded with just two: water and oil, in this case decanol. They recently published their results with two other co-authors in the journal Advanced Materials Interfaces.

Pushing and pulling

Appelman discovered the droplet dance by chance during an experiment for her master’s thesis. ‘Through the microscope, I suddenly saw that a droplet ‘popped’ and pushed the other droplets away.’ The oil droplets float just underwater. Once in a while, an oil droplet breaks through the water surface. From the droplet, a thin oil layer quickly spreads out. This happens due to the Marangoni effect, a physical phenomenon known from tears of wine. The outward flow pulls the underlying water, and the other oil droplets along it look like one drop pushes the rest away. Simultaneously, the oil layer evaporates and, therefore, draws more oil from the droplet, sustaining the outward pull. At some point, the oil layer disappears, and another drop pops. The cycle can repeat dozens of times.

Anyone wanting to try this at home will probably be disappointed. It won’t work with olive oil. ‘Olive oil consists of all kinds of long fatty acids, so the oil evaporates much more slowly,’ Deshpande explains. ‘Moreover, the droplets must be smaller than one-tenth of a millimetre in diameter.’ The researchers managed to produce them in the lab with special devices.

Synthetic cell

According to Deshpande, the discovery represents a possible building block for a synthetic cell – a human-made cell. ‘I want to build tiny vesicles that move like living cells. A cell can sense its environment and move in response. In a way, these oil droplets can do that.’ The next step is to build the oil droplets into the outside shell of the vesicles. ‘Maybe we can attach the oil droplet to the outside as a pocket so that the vesicle can respond to its environment and other vesicles.’

Writing alongside studies

It is not often that a master’s student appears as the first author of a scientific publication resulting from their thesis. Appelman wrote the article with substantial help from the co-authors. It was not easy. ‘Our manuscript was rejected five times by several journals. It took over a year and was a lot of work alongside my studies. But it was worth it.’

Oil droplets on water. Photo Shutterstock

Oil droplets on water. Photo Shutterstock