Text Rianne Lindhout

Ants that bite onto grass for hours on end , caterpillars that become hyperactive and climb to the treetops: these are the fascinating phenomena Simone Nordstrand Gasque studies. The weird behaviour is caused by parasites. How does that work?

As a Master’s student of Parasitology in Copenhagen, Simone Nordstrand Gasque used to get up at three in the morning to look for ants exhibiting abnormal behaviour in the woods. An infection with the parasitic flatworm Dicrocoelium dendriticum (the lancet liver fluke) makes the ants crawl into the vegetation and bite onto it. That increases the flatworm’s chances of getting inside the stomach of its next host: a grazing animal such as a deer.

Parasitism is a very successful approach

As Gasque explains, that is good for the parasite because it needs different hosts for the various stages of its lifecycle. It starts out as an egg in a snail, which is transferred to the ant when it eats the slime secreted by the snail, and then the larva ends up in a mammal, where the parasite matures into an adult.

With her research, Gasque was able to confirm for the first time in the field what had been suspected for 50 years, namely that infected ants only bite onto plants when temperatures are low. Gasque: ‘This usually happens at the start and end of the day, precisely when deer are grazing.’ If the ant is not eaten, it lets go of the grass when the temperatures rise again. ‘But on cold days, I saw ants that didn’t let go for almost the whole day.’

Treetop disease

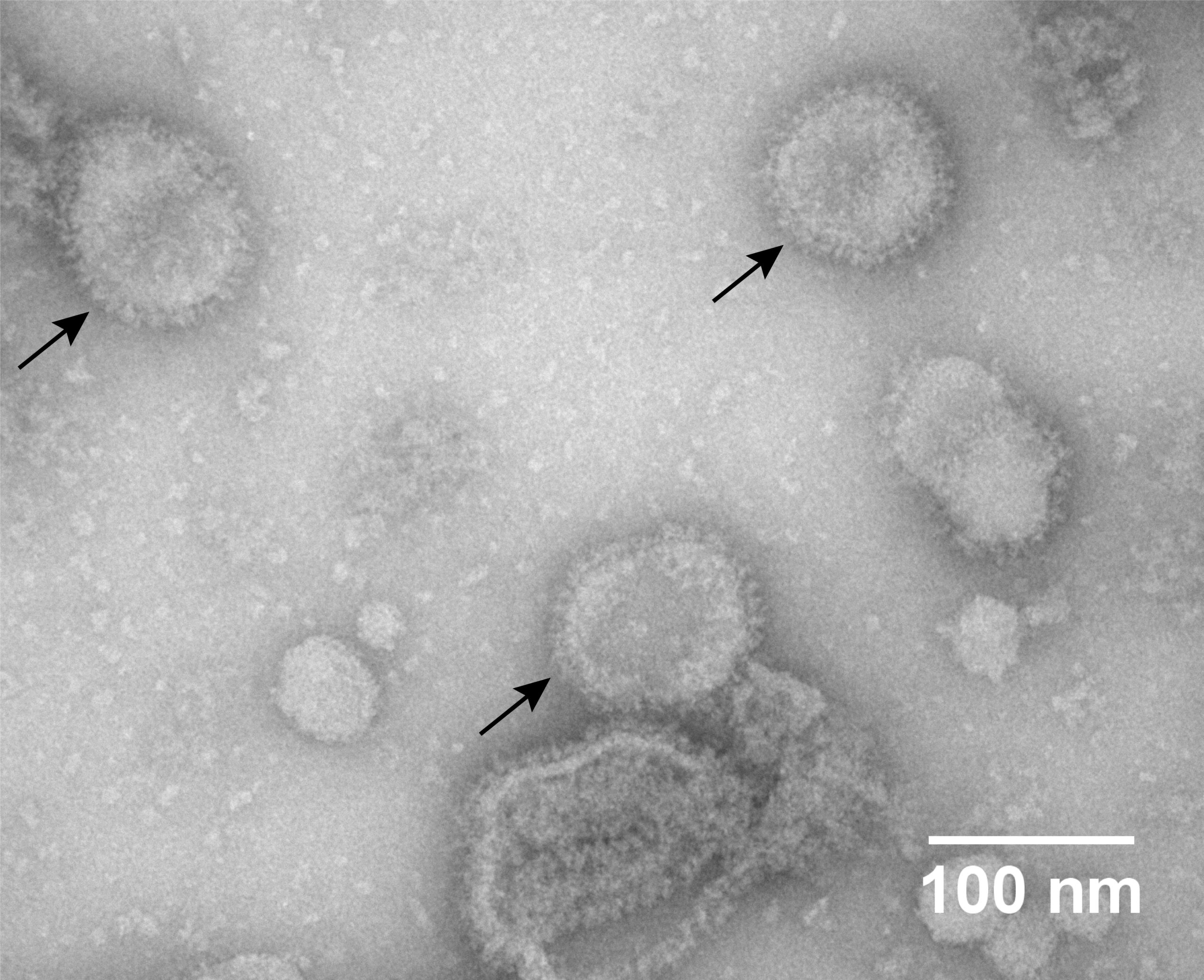

The Danish ants are not the only animal to show a change in behaviour following infection by a parasite, and the liver fluke is not the only culprit. After her Master’s in Denmark, Gasque came to Wageningen to study a similar form of zombie behaviour in caterpillars. In the Laboratory of Virology, where she is supervised by Professor Monique van Oers and Associate Professor Vera Ros, she is studying the caterpillars of the small mottled moth (Spodoptera exigua). The caterpillars turn into zombies after infection with a baculovirus. Gasque: ‘The caterpillars become hyperactive, which helps spread the disease. Sometimes they get what is called treetop disease: they climb to the top of a tree, where they die and turn liquid. The liquid drips down onto leaves that are then eaten by other caterpillars. And so the virus spreads.’

In the Laboratory of Virology, researchers are figuring out the molecular mechanisms that cause this behaviour. Which genes are involved in the host’s change of behaviour? The laboratory has years of experience in researching baculoviruses, which often cause deadly diseases in host insects. That is why these viruses are used in the biological control of pests in agriculture. Baculoviruses also make a good subject for research because they are easy to modify genetically and the effects of such modifications can clearly be seen in the changes in behaviour.

Blood-brain barrier

Gasque hopes to receive her doctorate in the spring of 2024 for her research on how the virus manages to reach the caterpillar’s central nervous system. To do this, it has to cross the insect equivalent of the blood-brain barrier. Many different scientists are interested in knowing how that is possible. For example, this knowledge could help develop medicines that can reach a brain tumour.

Gasque investigated whether certain proteins play a role here. ‘We know from earlier studies by our group that protein tyrosine phosphatase is needed to induce behavioural change.’ Gasque infected caterpillars with viruses where the protein had been genetically modified in a variety of ways. ‘Whatever changes we made to the protein, the virus always got inside the brain. That even happened when we removed the protein from the virus altogether.’ So this protein does not hold the key to the blood-brain barrier.

Autoimmune diseases

Incidentally, there are examples of behavioural change beyond the insect kingdom, says Gasque. Dogs become more aggressive when infected with the rabies virus, which helps spread that parasite. ‘If a dog gets involved in more fights, that increases the chance of infecting other dogs.’

‘Parasitism is a very successful approach,’ she continues. ‘It has existed for many millions of years.’ The definition of a parasite is an organism that profits from the relationship with the host whereas that host does not benefit from the relationship. But that is a grey area, according to Gasque. ‘There are indications that fewer autoimmune diseases are found in areas where a lot of people have intestinal parasites. That might be because the immune system is then too occupied to attack the person’s own body.’ One of Gasque’s teachers in Copenhagen put this theory to the test by infecting himself with a pig worm to cure his psoriasis. ‘That worked. There are now companies that grow pig worms for the treatment of people with an autoimmune disease.’

Here you see the underside of a big leaf, where many ants infected with Dicrocoelium dendriticum are displaying the behavioural change of biting on to the vegetation. The coloured number tags were glued onto the infected ants earlier. Photo Simone Nordstrand Gasque

Here you see the underside of a big leaf, where many ants infected with Dicrocoelium dendriticum are displaying the behavioural change of biting on to the vegetation. The coloured number tags were glued onto the infected ants earlier. Photo Simone Nordstrand Gasque