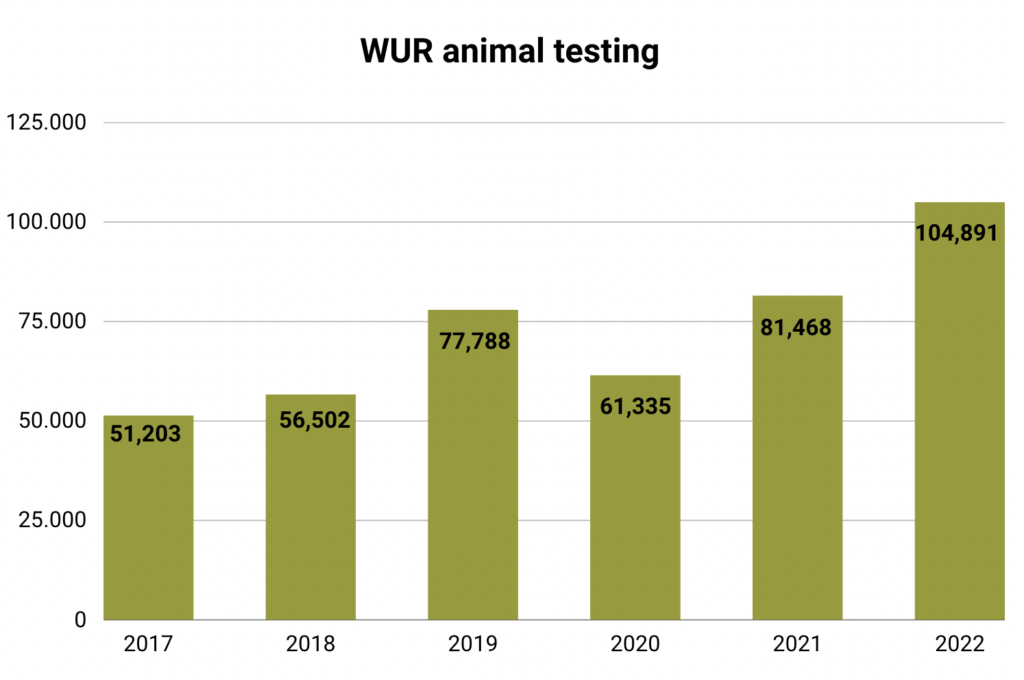

Last year WUR conducted more than 104,000 animal experiments – 29% more than in 2021. The vast majority of trials (80 percent) involved fish. The above figures are from the Annual Report on Laboratory Animals at WUR, which was published this week.

Since 2018, these annual reports have consistently described the progress in achieving the three Rs: Replacing, Reducing and Refining animal testing as much as possible, but the figures have been disappointing. WUR-wide, the number of animal experiments has shown an upward trend (see graph), with 2020 as the only exception.

When registering this data, a distinction is made between Wageningen University (WU) and Wageningen Research (WR). Moreover, it should be noted that the number of animal experiments differs from the number of laboratory animals because one animal can be used for multiple experiments. At WU, the number of laboratory animals decreased last year to 10,693, which is 17% less than in 2021, while at WR, that number increased to 94,198, about 27% higher than in 2021.

Primarily fish

As in previous years, fish (which have been statutorily defined as laboratory animals since 2015) comprised the vast majority of laboratory animals WUR-wide: 80%. The annual report cites as an example the thousands of glass eels that were provided with a tiny marker (a VIE tag) to track their distribution. The top five laboratory animals in 2022 were fish (80%), chickens (13%), mice (3%), pigs (1.2%) and cattle (0.6%).

At WR, most animal testing (83%) focused on species protection, usually involving monitoring of fish stocks. At WU, most of the animal testing focused on applied research (62%), especially involving animal welfare, such as a trial of feed additives for chickens to improve their intestinal and overall health.

Animal discomfort assessed

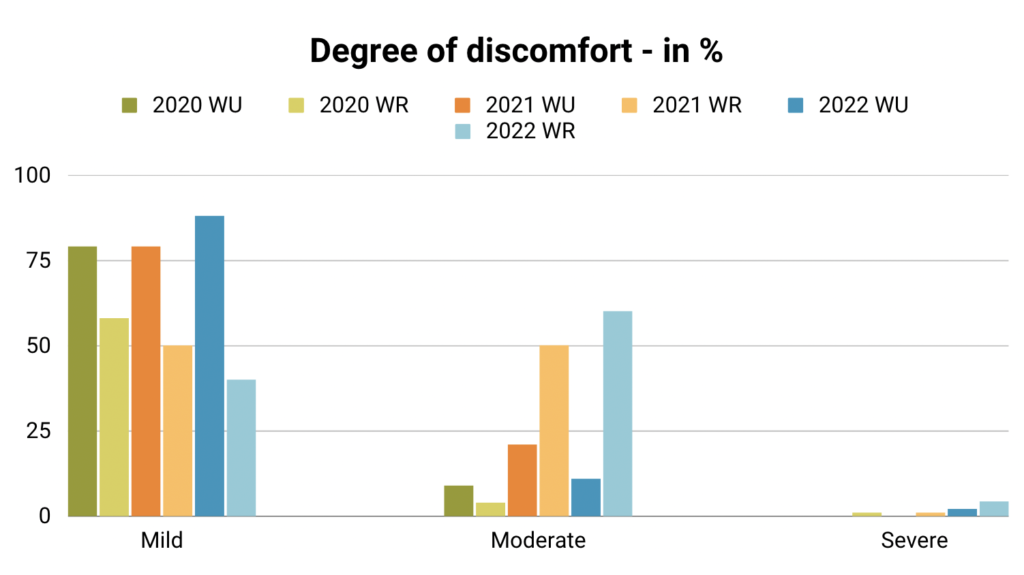

Because animal experiments differ greatly, WUR also reports the degree of animal discomfort. Several factors come into play when assessing discomfort, including the type of pain or fear the procedure causes for the animal and any permanent damage that results. The discomfort incurred during entire procedure is assessed and classified. Even when the individual steps in the procedure cause no more than ‘mild discomfort’, the discomfort of the entire procedure may still be classified as ‘moderate’, which is the second most serious classification. The worst classification is ‘severe discomfort’, which is infrequent at both WR and WU. In 2022, only 0.4% and 0.2% of animal experiments, respectively, were given this classification. At WR, the number of animal experiments in the ‘mild discomfort’ category decreased, but experiments causing ‘moderate discomfort’ increased. (Text continues below graph)

Full disclosure

Animal testing is formally the responsibility of Facilities and Services. But the Director of the Animal Sciences Group, Ernst van den Ende, also takes responsibility for the WUR policy on animal testing. He tries to be as transparent as possible about this type of research. “I also want to be visible in the public discussion on this topic. I want to show who we are, explain our attitude to animal testing and take responsibility for the tests we conduct,” he states.

“WUR has a small experimental animal centre for human biomedical research, mostly using mouse models. But we do perform many animal experiments that primarily involve research related to animal protection and health,” he explains. “Some of these ‘target animal experiments’ can potentially be tackled with other approaches such as organoids or artificial intelligence. But that requires a major change in our facilities. We are not that far yet.”

According to Van den Ende, however, that future is fast approaching. Through the four-year programme Next Level Animal Sciences ASG is investing considerable energy and funding (€12 million) in the development of technological innovations that can also provide alternatives to animal testing. “Still, technology can never replace all animal testing,” he stresses. “New vaccines or livestock rations, for example, eventually have to be tested on an animal at some point. I want to be perfectly clear about that.”

Fish are by far the most commonly used laboratory animals, and cattle are the least (less than one percent). Photo: Resource

Fish are by far the most commonly used laboratory animals, and cattle are the least (less than one percent). Photo: Resource