The floodplains near Wageningen narrowly escaped development with lots of high-rise buildings 50 years ago. Thanks to opposition from concerned people at WUR.

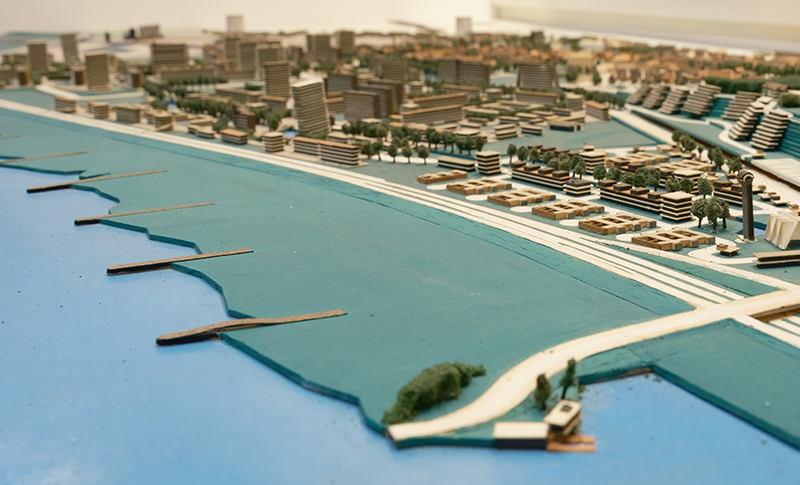

What is the most popular walk in Wageningen? Undoubtedly the one along the dyke that skirts the town centre. It’s a delight in all seasons and at any time of day. So take a good look at the picture accompanying this story. Or even better: the related scale model in De Casteelse Poort museum. The floodplains as envisaged 50 years ago, with high-rise buildings as far as the eye can see. Manhattan on the Rhine.

The megalomaniac plan was swept off the table thanks to the D66 Housing minister Hans Gruijters, who scrapped it. But just as much thanks is due to people like Beatrice Kesler, then a university lecturer at the Agricultural College. She and her allies – most of them from the College – doggedly fought the plans to build on the floodplains. At the end of this month, Kesler – now 81 – will give a lecture on that battle for the landscape.*

Opposition

Kesler really got involved in the opposition to the plans in 1969 pretty much by chance, she says on the phone. She has now been living in northern France for over 20 years, running La Gabrielle holiday accommodation. ‘I was living in De Nude at the time. I was married, had a baby and had just graduated from the Agricultural College as a residential ecologist. These plans for the floodplains had existed for a long time, but I had never really looked into them. Until one day I was approached with the question whether I knew anything about demographics and population growth. A group was working on an objection to the building plan. They wanted to know if the demographic data it was based on were correct.’

At that time, the plan to build all over the floodplains was already at an advanced stage. The seed had been sown as early as 1951 by Mayor Maarten de Niet. ‘De Niet was a man with a mission,’ says Kesler. ‘The town needed more allure and he wanted to facilitate the growth of the Agricultural College and institutes in the city. This required a substantial expansion. The problem was that the Agricultural College owned almost all the land around the town and used it for experimental plots. So De Niet turned his attention to the floodplains, seeing no other option. But nobody has ever seriously questioned the inviolability of those experimental plots.’

Unlikely

Kesler soon realized that the projected population growth was improbable. ‘The mayor’s firm belief was that the town was going to grow. But the figures were highly unlikely. They thought there would be 14,000 students in the 1990s. WUR has only just reached that number now. In terms of population growth, they counted on a city of 45,000 to 50,000. The population still hasn’t reached that level. But such growth called for 5,600 new homes.’ The real shock came when she studied the plans herself. ‘My hair stood on end. Ninety per cent of the construction consisted of high-rise buildings, with blocks of flats of up to 15 storeys. At the time, Wageningen already had the Pomona flats and the ones on Asterstraat. That was quite enough high-rise for such a small town.’

Kesler joined the concerned citizens a year after the town council had approved the zoning plan. The province had ratified it in 1969, despite objections. All that remained was the proceedings at the Council of State. The plan came up for discussion twice there: first in 1972 and then a modified plan with fewer high-rise buildings was discussed in 1975. Kesler addressed the latter session. Only three members of the initial opposition group were left, due to relocations. ‘But various campaigns and publicity spurred others into action too. An issue that initially only interested people at the municipal council and in the Agricultural College administration had now reached the ears of town residents. And they did not support the floodplain plan at all.’

Party

Apart from high-rise buildings, the plan was controversial for other reasons too. Kesler: ‘It was clear from the start that it was going to be very expensive. The dyke had to be raised, and the whole site had to be raised by one and a half metres. All the infrastructure had to be built at once. Because it was so costly, high-rise buildings were needed to make it viable. Later, the plan was revised to cater for the objections to high-rise buildings. But then the houses became so expensive that no social housing was possible.’ In the spring of 1976, seven years after the town council gave the plans the green light, minister Gruijters ditched them once and for all. Against the advice of the Council of State, incidentally. So was it party time? ‘Oh no,’ says Kesler. ‘As far as I can remember, we weren’t directly informed of the minister’s decision. We just read about it in the newspaper.’ But that didn’t diminish the satisfaction. Kesler still visits Wageningen and its floodplains very regularly. ‘My daughter lives there and my granddaughter studies at WUR. I still walk along the dyke regularly. The floodplains have become a beautiful nature reserve. What do I think of that? I think, we nailed it in the end!’

*Beatrice Kesler’s lecture is on Tuesday 28 February at 20:00 in the Wageningen Public Library. Admission is free.

The model of the floodplains plan: the expansion of the town would consist of 90 per cent high-rise buildings, with 15-story flats. Photo Guy Ackermans

The model of the floodplains plan: the expansion of the town would consist of 90 per cent high-rise buildings, with 15-story flats. Photo Guy Ackermans

![[Seriously?] New year swim postponed until July](https://www.resource-online.nl/app/uploads/2024/01/WEB_De-neus.png)