In 2001, the current EU directive on genetically modified (GM) crops made their cultivation in Europe almost impossible. That position seems due for revision now, in the light of new techniques, applications and understanding.

Agroecologist Bert Lotz has been researching and debating this issue for more than 25 years. In 2023, the European Commission will come up with a proposal for revising the directive. ‘And that’s big news,’ says Lotz. His first research on GM crops was done in 1996. At the behest of the Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality, he and his colleague Jos Bijman did a literature study on what was known about the risks and opportunities associated with the first GM crops in America. ‘I will never forget the day I presented that report in The Hague. On the same day, Greenpeace were protesting at Rotterdam port. They blocked the first ship seeking to dock in Europe with a cargo of GM soya for livestock feed. We made the front page of the Volkskrant newspaper right away. Neither Greenpeace nor the US GM soya producer Monsanto agreed with our report. As a researcher, I was used to staying behind the scenes. It took a few days to sink in.’

Awkward introduction

The outcome of that first report was a nuanced conclusion. It was about crops that had been modified to be resistant to the herbicide Roundup, or glyphosate, so that the crops go on growing when the grower sprays against weeds. The researchers saw risks, especially for the development of resistance to Roundup in weeds.

We made the front page of the Volkskrant right away

But there also seemed to be opportunities: with a limited use of Roundup at the right time, and as a complement to mechanical weed control, spraying against weeds could be significantly reduced. ‘Findings that still stand today,’ confirms Lotz. ‘The first resistant weeds showed up within four years.’ And that actually led to even more Roundup being used. ‘In retrospect, that was an awkward introduction of Monsanto’s first application for a GM crop.’ It set the tone for the genetic engineering debate. In 2001, the EU adopted legislation that made the admission of GM crops almost impossible.

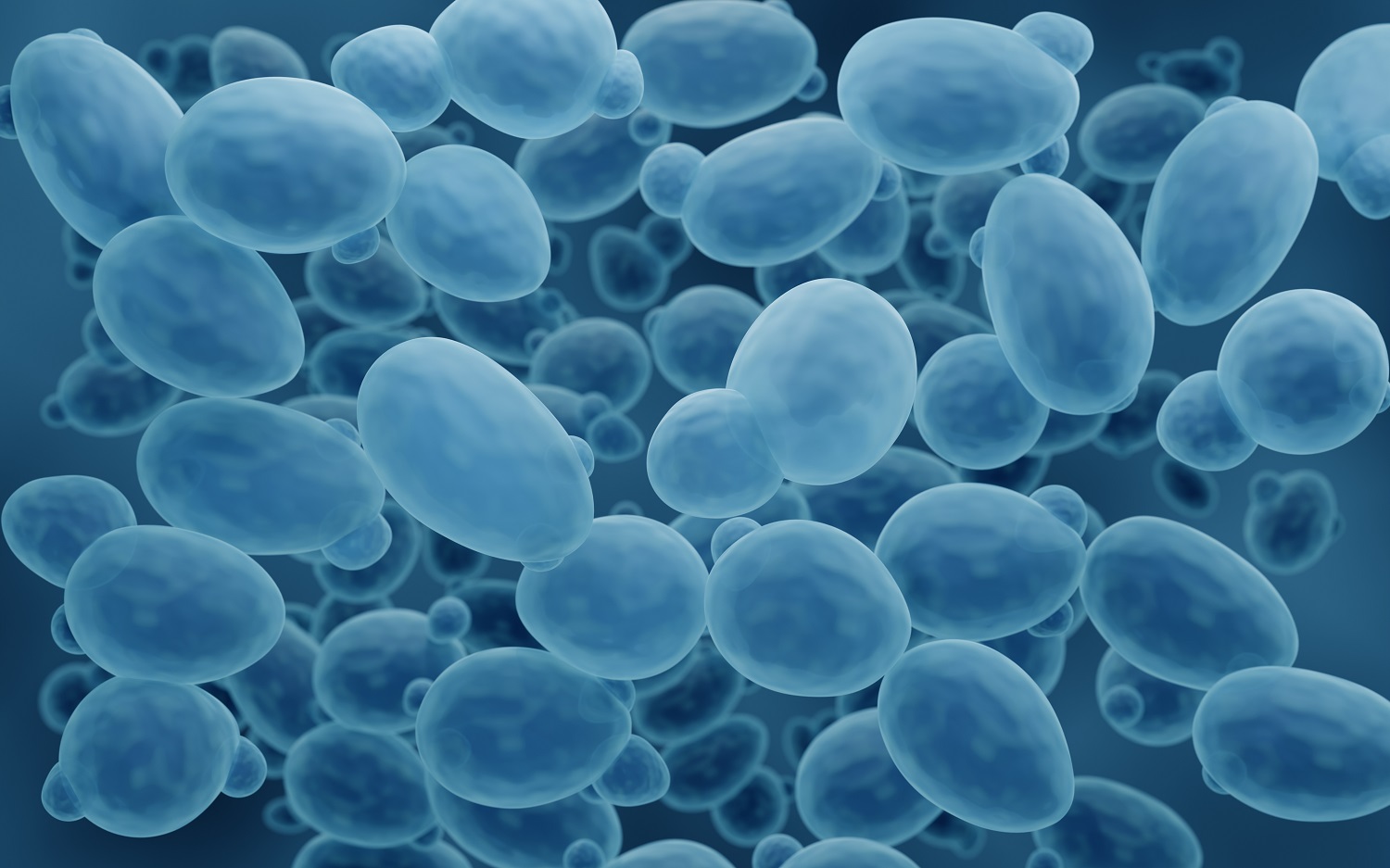

Much has changed since then, and a better understanding of the risks and new DNA techniques have made the debate relevant again. A big first step towards this was the emergence of Bt crops such as corn plants with a gene from the Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) bacterium, which produces a substance toxic to specific groups of harmful insects. ‘The beauty of this crop is that the benefit is very clear: the grower doesn’t need to apply nearly as much insecticide.’

Cis or trans

The next step came with a project Lotz himself participated in, the DuRPh programme that ran from 2006 to 2016. In this programme, Wageningen researchers worked on a potato with multiple resistance to Phytophthora disease. This time, not with genes from other species, but with genes from wild varieties of the potato. They called this form of genetically engineered breeding cisgenesis, as opposed to transgenesis, which makes use of genes foreign to the species. ‘With conventional breeding it would take decades to make an existing potato variety multiply resistant, whereas with genetic engineering it can be done in a few years. Based partly on our research, the European Food Safety Authority has concluded that cisgenic potatoes are as safe as conventionally bred varieties.’ The potential benefit is a massive decrease in the use of fungicides.

Editing more precisely

The last important development was the discovery of CRISPR-Cas. For the first GM crops, researchers used the bacterium Agrobacterium tumefaciens to insert new DNA into crops. This bacterium can do this naturally, but the method has two drawbacks. You cannot determine where the new gene ends up in the plant genome, so it could end up in the wrong place, where it harms the plant. And secondly, a small amount of bacterial DNA always stays behind in the plant. ‘Although within the DuRPh project we have managed to minimize this with smart techniques.’ Another advantage is that CRISPR-Cas can also be used for very minor modifications.

Cisgenic potatoes are as safe as conventionally bred varieties

For example, recent research by Wageningen Plant Breeding shows that particular resistance genes are already present in potatoes, but in a deactivated form. ‘With CRISPR-Cas you can switch those genes back on. That’s called gene editing.’

Public opinion

Lotz has seen a gradual shift in public opinion on GM crops. Part of the DuRPh project involved participating in the debate on the cisgenic potato, and he talked to political parties, churches, farmer organizations, students and other groups. ‘More and more groups are now seeing opportunities for using techniques like cisgenesis to make agriculture more sustainable.’ A party like Greenpeace remains vehemently anti, although the opposition seems to have become less visible. ‘I always used to know the campaigner involved, but now I don’t know who they are.’

In the second quarter of next year, the European Commission will come up with a proposal for a new directive. ‘That’s really big news, although it then has to be voted on.’ An exciting time, for WUR too. ‘I suspect that if restrictions are eased, a lot of plant breeding companies will head to Wageningen to join forces in new research.To develop crops with disease resistance or drought tolerance, for instance, or gluten-free grains.’

Lotz expects that easing of EU rules will come and that cisgenic and gene-edited crops will gain easier access to the European market. ‘But it remains to be seen exactly how they’ll go about that.’

1994: First GM crop, a tomato that keeps longer

1996: First Roundup Ready soya on US marke

2001: EU regulations, GM crops banned

2006: Start of DuRPh project with cisgenic potato

2013: First GM crop created with CRISPR-Cas

2018: EU labels CRISPR-Cas as a GM technique

2023: European Commission proposal for updating legislation

Agroecologist Bert Lotz: ‘I suspect that if restrictions are eased, a lot of plant breeding companies will head to Wageningen’. Text: Tanja Speek. Photo: Guy Ackermans

Agroecologist Bert Lotz: ‘I suspect that if restrictions are eased, a lot of plant breeding companies will head to Wageningen’. Text: Tanja Speek. Photo: Guy Ackermans