Let’s start by introducing them: Noë Baljet (23, Nutrition and Health), Floris Helmendag (20, Molecular Life Sciences), Tanguy Heesemans (24, Molecular Life Sciences) and Nikoline Marxen (23, Environmental Sciences). Students from a diverse range of disciplines, all participating in the Honours Programme.

For that programme, Baljet recently organized an activity focused on speechmaking, with the mayor of Wageningen; the other three are working together on a research project on drug residues in wastewater; and soon there will be a symposium with European Commissioner Frans Timmermans. And all this comes on top of their regular degree programme. What does the Honours Programme actually entail? And more importantly, is it worth all the effort?

The programme

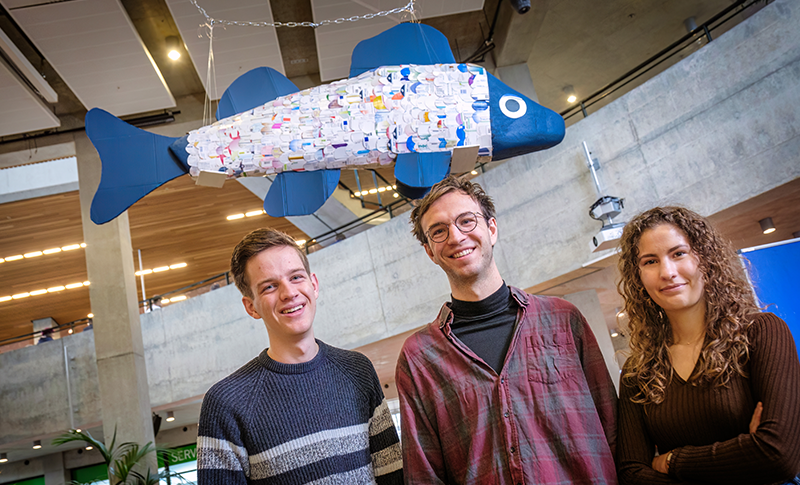

Honours students work on three dimensions over two years of their Bachelor’s programme: broadening and deepening their knowledge, and personal development. The broadening usually takes the form of the Honours Investigation Project (HIP): a two-year multidisciplinary research project for which nine credits are awarded. A coach provides the topic, but the content and form are up to the students themselves. Floris, Tanguy and Nikoline made a fish (see photo), together with their HIP peers.

Floris: ‘This project is about drug residues in wastewater. They are hard to filter out and that causes problems in nature. Some fish suddenly change sex because of these drug residues, for instance. Currently, medicines that are past their use-by date or are no longer needed get discarded and end up in the wastewater. It would be better if we collected them at pharmacies, where they can be disposed of correctly. We’ve launched a campaign to this end. We want to draw attention to the issue with this fish, whose scales are made of medicine packaging.’ Tanguy: ‘We are also going to measure the impact: whether more people actually start handing in surplus drugs at the pharmacy.’

Noë Baljet sought added breadth not in an HIP, but through an activity: a training course in public speaking over two evenings. Noë: ‘That way you practise leadership, instead of just talking about it. On the first evening, we invited the mayor of Wageningen to come and tell us what makes a good speech. On the second evening, students gave speeches in front of a jury.’

Floris too has invited a prominent public figure: ‘European Commissioner Frans Timmermans is coming here on 7 December to discuss climate policy with students. Everyone is welcome by the way, including non-Honours students.’

Besides broadening their knowledge, Honours students must also deepen it and work on their personal development. The extra depth is sought through an assignment the students have to think up for themselves. Together with Floris, Tanguy devised a new practical for a course. And Nikoline and Tanguy explored a possible application for data collection in Mathematics: ‘I felt the lack of application on that course. It stayed abstract, whereas I wanted to know what you could do with it.’ For the personal development component, students attend a leadership weekend and shadow a leader from the political scene or the business world. There is also a tutor, who coaches students in their personal development.

The benefits

A recent study on the Wageningen Honours Programme highlighted the positive long-term effects of the programme. Honours alumni say that the programme improved their ability to transcend disciplines and to tackle complex problems. Noë: ‘I think Honours opens doors. I meet all sorts of interesting people and widen my network that way. And I get to know myself better and learn to recognize my limits. Because sometimes I’ve sat with my head in my hands wondering: how am I going to get through this horrendously busy week? That was instructive.’

Floris recognizes this: ‘You are really thrown in at the deep end. That is hard but it’s also one of the programme’s strong points. You have a lot of freedom and autonomy and that helps you learn to find your own way.’ In retrospect, Nikoline is also glad there wasn’t too much guidance and supervision: ‘I did feel a need for it at first, but now I’m actually glad we figured it all out ourselves.’ The full Honours Programme does put a lot of pressure on the students. Tanguy: ‘It requires dedication and sometimes sacrifices. Sometimes you spend your Saturday morning working on something. But I think it’s worth it.’

Not for everyone

Students whose grades are in the top 10 per cent in periods 1, 2 and 3 get invited to apply for the Honours Programme, but others are free to apply as well. Ultimately, the Honours Team coordinators decide which 60 students get to join.

The programme doesn’t suit everyone, as it turns out. Students Gerwin Pol (23) and Daphne Schoop (25) quit the programme after a few months. Daphne: ‘With my social sciences degree, I was the odd one out in our HIP group. I found it difficult to contribute based on my talents and interests. Guidance in this area could have helped us a lot, on how to make decisions as a group, for example. I decided to do a board year; I got more energy from that.’

Gerwin: ‘I didn’t feel comfortable with the idea that the best-performing students get extra attention and resources from the university. I still think we should strive not for equal opportunities but for equal outcomes, so that students from all backgrounds can keep up.’

Interested? You can apply up until the end of January.

Honours students Floris Helmendach (left), Tanguy Heesemans and Nikoline Marxen made a fish from medicine packaging to draw attention to the issue of drug residues in wastewater. ‘Some fish suddenly change sex because of these drug residues, for instance.’ Photo: Guy Ackermans

Honours students Floris Helmendach (left), Tanguy Heesemans and Nikoline Marxen made a fish from medicine packaging to draw attention to the issue of drug residues in wastewater. ‘Some fish suddenly change sex because of these drug residues, for instance.’ Photo: Guy Ackermans