Carcasses play an important role in the natural cycle. PhD student Elke Wenting seeks to understand that role.

In a clearing on the Veluwe, several dead fallow deer are rotting away. There is nothing unusual about that in itself. They don’t get cleared away in this area, explains ecologist Elke Wenting (Wildlife Ecology & Conservation). But there is something special about these fallow deer: they are part of Wenting’s study of how carcasses contribute to the cycle of scarce nutrients such as zinc, cobalt and selenium. ‘The idea is that animals have a big impact on that cycle of trace elements,’ Wenting explains. ‘Through their diet, they get those scarce substances from all over the place. When an animal dies, there is a relatively high concentration of those substances at the site of the carcass. The question is what happens to them. Are they eaten and dispersed by scavengers or do they disappear into the soil?’ Wenting’s fallow deer should give us some idea.

Secret

The fallow deer are local, but Wenting prefers to keep the location to herself. ‘Anyone is welcome to know what I do, but not where I do it. There is expensive equipment here, and I don’t want the trial to be disturbed.’ The site is not likely to attract casual visitors either. It is tucked away out of sight and if that’s not enough, a double electric fence will do the rest. But the fence is there to keep animals out, rather than people.

Wild boar really do eat everything

‘I use it systematically to keep certain groups of animals away from the carcasses, to see how important they are for the nutrient cycle. A little way away lies a carcass which all the animals can reach. There is one place with a wildlife grid that only keeps out wild boar. Here, where we are now, only birds can reach the carcass, and over there, only insects.’

Decomposition

A power supply is essential for keeping animals out, and Wenting has to visit the site every week to change the batteries. A solar panel on the site helps, but it can’t provide all the power required. ‘Changing the batteries is the biggest job here,’ says Wenting. Along with taking monthly samples of the soil under the carcasses. A special hoist has been developed for that purpose, to lift the animals carefully and put them back in exactly the same place after the sampling. Those samples will be examined for their chemical composition. Fallow deer were chosen as test animals for mainly practical reasons. Wenting: ‘Roe deer are not shot here and red deer are too heavy to lift.’ The carcasses are in various stages of decomposition. The rate at which that happens varies per animal. ‘It’s impossible to make sense of,’ says Wenting. ‘And we don’t know why it is. There are a lot of scavengers here, because for several decades now there’s been a policy of leaving carcasses on the spot. Some carcasses are gone within three to four days, but others are lying there four months later looking as though they were shot yesterday.’

Boar

It has become clear, though, that wild boar can play a role in the disposal of carcasses. Wenting discovered this from an experiment in which carcasses at various locations around the country were kept under surveillance with cameras. Wenting: ‘With these, we tracked the stages of decomposition, the species of animals involved and how they behaved near the carcass. Which tissues do they eat and at which stage of decomposition are they active? And wild boar really do eat everything. They also come in larger groups. Wild boar are scavengers. They need animal proteins on top of acorns and the like. Boar can speed up the process tremendously, but they don’t always do so.’

An aspect of the cycle Wenting is trying to document is the chemical composition of animals. With remarkable results. Wenting: ‘It’s always been assumed that the chemical composition is very consistent in animals, unlike in plants. After all, they can move around and take what they need. But it turns out that is not the case at all.’

Anyone is welcome to know what I do, but not where I do it

She found this out when she compared otters and fallow deer, two species that have little in common. Otters appear to have a much more constant chemical composition than fallow deer. ‘In addition, there appeared to be quite a lot of variation within the species. That raised the question of how that would be within the same environment. I then studied red deer and boar from my study area, also looking at where in the body those nutrients are stored.’

Remarkable

These results – which are yet to be published – are even more remarkable. ‘I am finding big differences. Not only between the two species, but also per individual. It’s impossible to predict where in the body the trace elements will end up.’ And that is interesting news. Organs like the liver or kidney are often used as indicators of the presence of certain substances in an area. ‘But I see in my study that it is not as straightforward as that. One red deer, for example, had masses of lead in its lungs. So that one was seriously ill, in fact. In such a case, if you look for a cause in the liver alone and you find nothing, you can draw very wrong conclusions. So it’s not enough to analyse a single organ as a measure of the whole.’

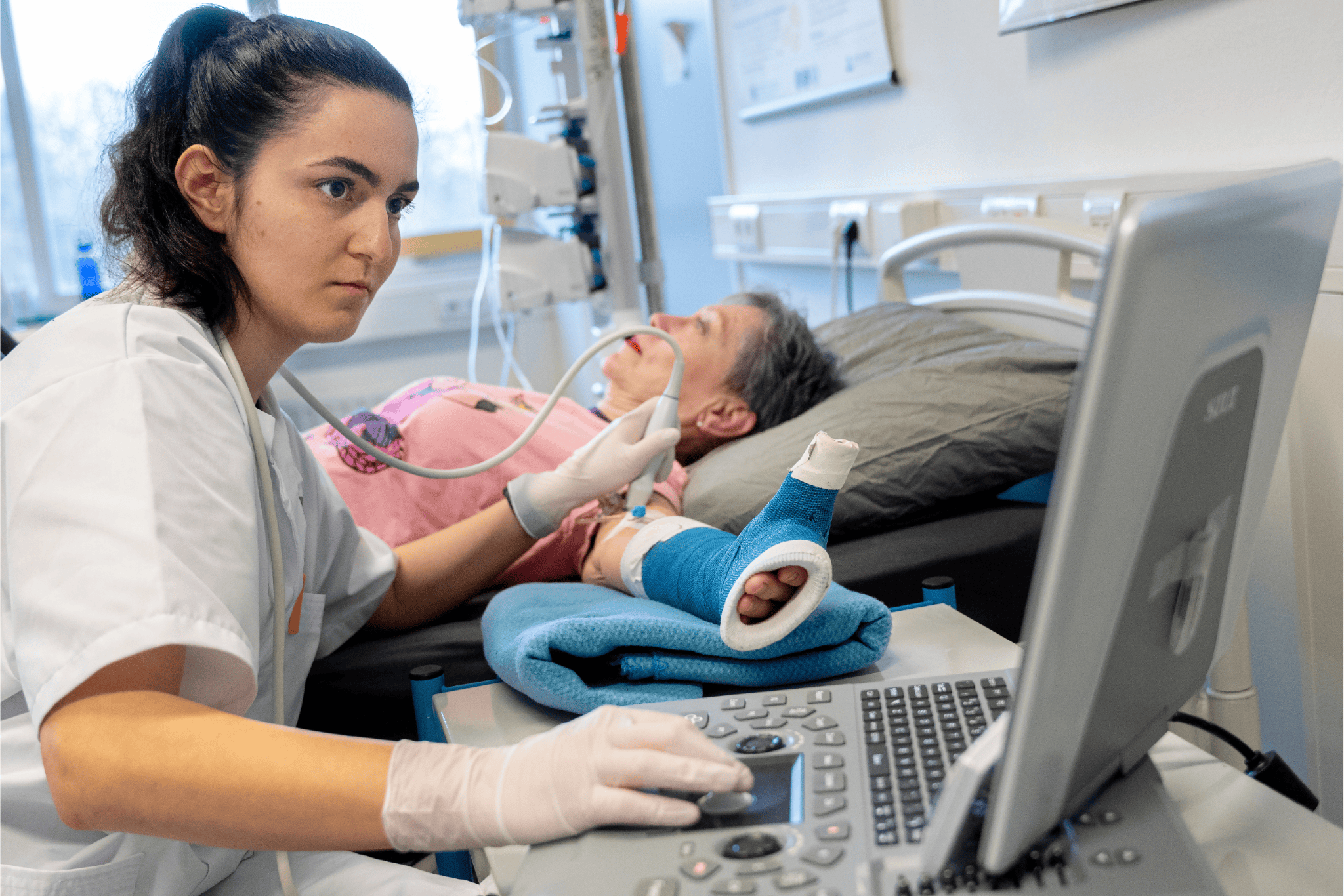

Elke Wenting with one of the dead fallow deer. Photo: Guy Ackermans

Elke Wenting with one of the dead fallow deer. Photo: Guy Ackermans