Last month, the Dutch Cabinet announced its intention to generate twice as much wind energy at sea by 2030 as was previously planned. Such a significant increase in scale has implications for life on and in the North Sea. And therefore also for Wageningen research on marine life.

Offshore wind farms are a relatively new phenomenon in the Netherlands. The first wind farm came on stream 15 years ago off the coast at Egmond aan Zee. It has 36 turbines and a capacity of around 100 megawatts – enough to supply about 100,000 households, or a city the size of Eindhoven, with electricity. Large-scale wind production has only been present in the North Sea since 2016, when Gemini wind farm set a new standard: 150 turbines and 600 megawatts, a global first at the time. At around the same time, the costs at last began to fall, and as a result government subsidies have not been necessary for offshore wind farms since 2018. Offshore wind has since been given a bigger and bigger role in the Dutch energy transition (see inset).

The North Sea is now being transformed into the Netherlands’ main source of energy. This inevitably has an impact on marine life, but what impact? Wageningen Marine Research has been researching this since around 2000. Coordinator and team leader Josien Steenbergen estimates that there are now about 40 people working on this theme – ‘not all of them full time, though’ – and that the research budget is about 3 million euros per year. The researchers are working on a wide range of topics. Examples include mapping the flight patterns of migrating birds and bats over the North Sea, finding out how much sharks and rays are bothered by the electromagnetic fields of undersea power cables, and identifying opportunities offered by wind farms located outside fishing grounds for commercial seaweed farming. Although private parties are increasingly interested in research – more on this later – the Wageningen researchers work primarily on behalf of central government. Together with NIOZ and Deltares, Wageningen Marine Research is one of the larger research institutes within the government’s programmes Wozep (wind at sea ecological programme) and MONS (monitoring, research, nature enhancement, species protection). MONS is a 10-year research programme due to start in the course of this year, which has been developed with input from Wageningen Marine Research.

Next level

According to Steenbergen, the cabinet’s decision to more than double the use of offshore wind has brought things to the next level. ‘The research done so far has produced the knowledge we needed about the effects on specific species – and how to limit the damage, for example by using “bell screens” to keep porpoises away from the wind farms or by shutting down the turbines when flocks of birds or bats approach.

Ecology does not end up at the top of the list of selection criteria

But there is still a tremendous amount we don’t know at the population level, and even more so at the system level. And that knowledge will become even more important as more wind farms are constructed in the North Sea.’

Asked whether Marine Research was involved in the selection of the three recently designated new areas, Steenbergen says: ‘To a limited extent. Two years ago we ran a workshop for the Public Works directorate on which areas in the North Sea are important for which animals. The maps that a colleague made then of the seabird habitats were used by the ministry in the selection process. The tricky thing is that an awful lot of factors are involved in the selection of the wind farm locations: from defence interests to shipping routes to fishing grounds and Natura 2000 areas and underground cable routes. These factors are all topographically fixed, while ecology is not usually. So unfortunately, ecology does not tend to end up at the top of the list of selection criteria.’

Simultaneous

The upscaling of offshore wind energy increases the urgency of a solid knowledge of its ecological implications, says Steenbergen. Her view is: ‘It would be good if, on top of the research already going on, additional modelling studies followed to chart the cumulative effects. And preferably from as broad a perspective as possible, because in addition to the wind farms, there are many other factors that put pressure on the North Sea, including shipping, fishing and sand extraction. All that affects marine life as well, so you can’t study the different factors separately from each other.’

But isn’t it a bit late to be starting this kind of study, knowing that the new wind farms have to be up and running by 2030? ‘There is a risk of a mismatch between the pace at which the necessary knowledge becomes available and the pace at which offshore wind develops,’ agrees Steenbergen. ‘So a degree of adaptability will be important. Research often provides insights as you go along that can guide further action.

There is still much we don’t know at the population level, and even more so at the system level

But some studies simply take time. If in MONS we set up a basic monitoring programme for phytoplankton or small pelagic fish species*, we cannot do without multiannual data sets. That kind of monitoring poses a methodological challenge anyway, because we are measuring in a system that is in fact already changing: some of the wind farms are already under construction. All the more reason to approach the research with care and not to jump to conclusions.’

Partners

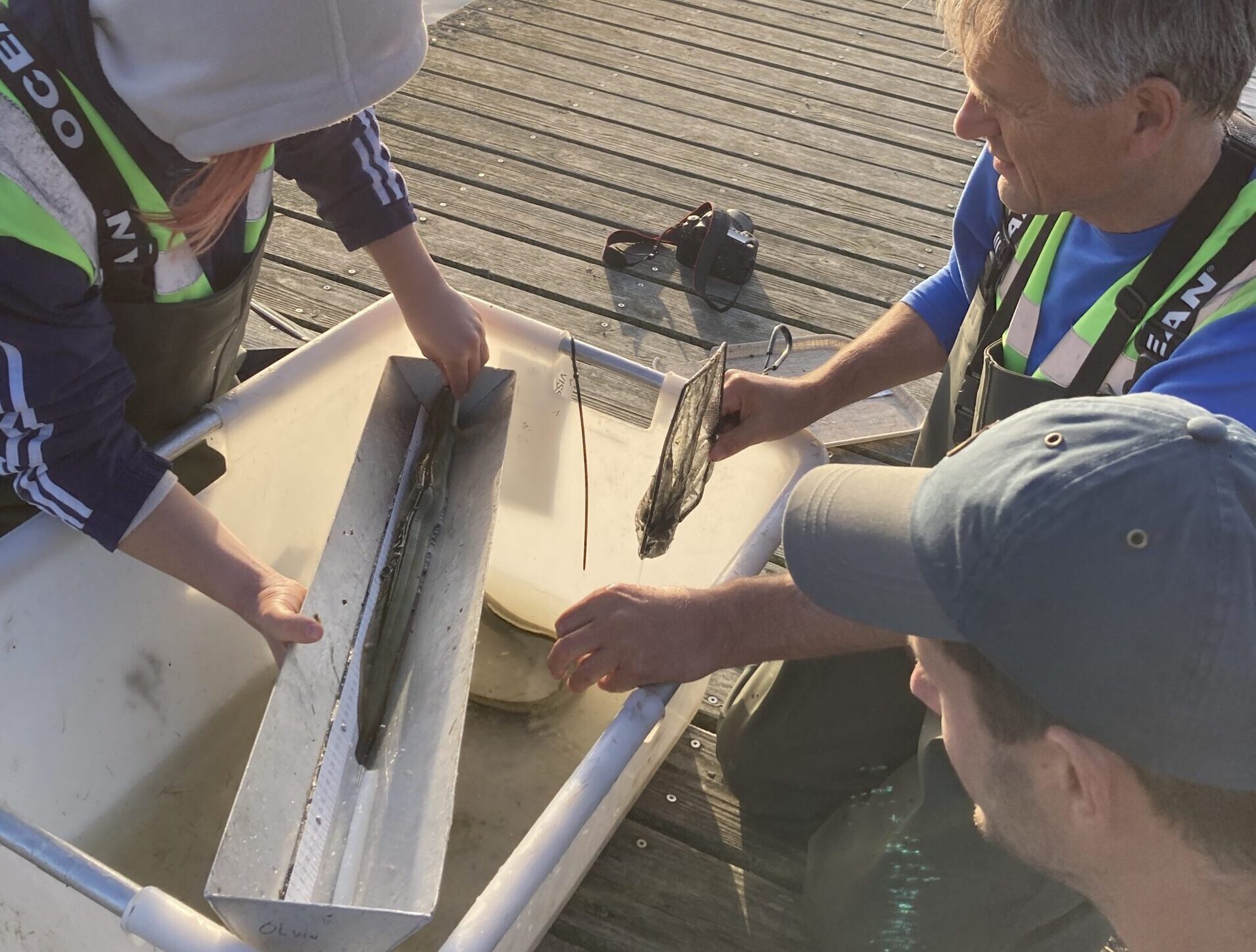

Besides the government, Marine Research increasingly often works for private parties such as wind farm developers. ‘In the most recent tender for a location, the government took ecological aspects into account. Our knowledge is welcome, because the more nature-inclusive the wind farm design, the more points it scores in the tender,’ explains Steenbergen. Marine Research is also working with partners to investigate multiple uses of the wind farms. Trawling is not permitted in the vicinity (there are quite a few cables in the seabed) and that offers opportunities for other forms of fishing or farming, not to mention nature restoration. Efforts are ongoing, for example, to bring the flat oyster back in the North Sea and there are experiments with artificial reefs to increase underwater biodiversity.

Apart from wind farms, there are many other factors that put pressure on the North Sea

Steenbergen notes that it is important to remain critical of these initiatives. ‘You might well question whether hard reef structures should be encouraged in places where the seabed was originally sandy. Or what effect all those extra shellfish mouths have on the nutrient levels in the water.’ Practical feasibility can be an issue too, as it is for ideas about fishing in wind farms, for example. ‘The safety requirements are so stringent that in the four years of our pilot project in Amalia Wind Farm, the conditions have never been right for a fisher to actually enter the wind farm. But there are a few young, enthusiastic fishers who would like to go into the wind farms, so we continue to look for opportunities. We are working closely with Wageningen Economic Research on this dossier, incidentally.’

Worst case

These two institutes, Wageningen Marine Research and Economic Research, are also working hard on the governance of offshore wind, explains Steenbergen. ‘There’s quite a lot that scientists don’t know about the effects of offshore wind farms. We will find many answers in the coming years, but they may not all be entirely positive. Suppose we discover that the North Sea system is seriously disrupted, or that a particular species is seriously endangered by the wind farms? What should we do then? Does the wind farm go out of business? Or do we accept the loss of nature, because the Netherlands cannot do without offshore wind energy for its energy transition? And is that legally permissible? No one can answer that yet. We need a proper assessment framework which gives all the ecological, economic and social interests the weight they deserve. The Netherlands really needs to start thinking about those kinds of difficult questions, especially after announcing the doubling of offshore wind capacity.’

* Fish species that swim at all levels in the water, such as mackerel and herring. As opposed to demersal fish species such as red gurnard and sole, which live close to the seabed.

Wind energy in the North Sea

Previous governments had already designated six large wind areas to generate some 9.8 gigawatts of additional offshore wind power by 2030. Last month, the cabinet added three new areas: Nederwiek, Lagelander and Doordewind, which will generate 10.7 gigawatts between them. By 2030, the Netherlands wants to have a total offshore wind capacity of about 21 gigawatts. This will make the North Sea by far the main source of energy for the Netherlands. Source map Rijksoverheid.nl

A new offshore wind farm near the Dutch coast. Photo Shutterstock

A new offshore wind farm near the Dutch coast. Photo Shutterstock