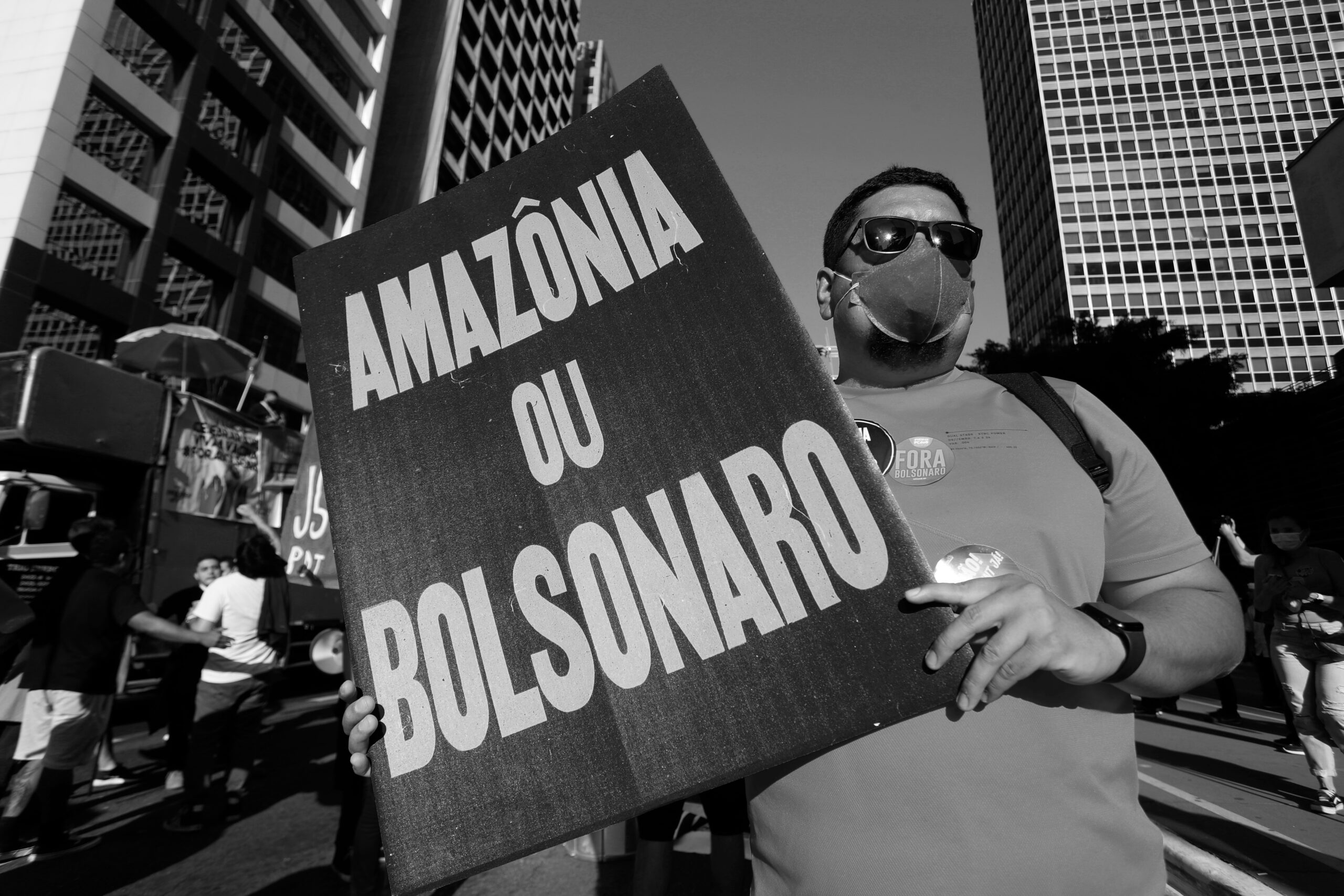

Brazilian scientists are trying to combat deforestation and illegal mining, but the government is not on their side. Under Bolsonaro, the trend for cutting budgets has continued and anti-science sentiment is spreading. How are Judith Verstegen’s fellow researchers in Brazil holding up?

University lecturer Judith Verstegen (Geo-information Science and Remote Sensing) sees at close quarters what it is like when you can’t take the pursuit of independent science for granted. Among her close collaborators are the Brazilian researchers Gilberto Câmara and Michelle Picoli. Câmara has worked at INPE since 1980 (see inset) and was director there from 2005 to 2012. He is retired now, but continues to work voluntarily as a senior researcher at the institute. Without people like Câmara, the institute’s research would have gone into a serious decline. INPE’s budget today is 85 per cent lower than in 2010, with inevitable consequences. ‘There is less money for research and fewer staff. People are not replaced when they retire,’ says Câmara. ‘And in the case of INPE, there is less scope to do research the government doesn’t like.’ As examples, he mentions studies on illegal mining in protected areas and the monitoring of deforestation in the Amazon and Cerrado.

It is not just financially that the cards are stacked against the scientists. ‘The current director of INPE was nominated by Bolsonaro,’ says Câmara. ‘They replaced the previous director, a scientist, with this puppet.’ Câmara’s research was opposed internally by the director, Clezio Marcos de Nardin. ‘Judith Verstegen and I wanted to submit a research project,’ he begins. ‘Because I am connected with INPE, my proposal had to have the director’s approval, which he withheld. I took him to court, but the judge sided with him, even though he was lying. I am a researcher at INPE, but he said I had no ties with the institute.’ This only strengthened Judith Verstegen’s resolve to continue working together. ‘When that proposal was blocked, I could have decided never to work with Brazilians again. But I’m not like that. This is happening because of the political climate. Now of all times I should do my best to maintain my relationship with the scientists, because they need our support.’

‘Now of all times I should maintain my relationship with the scientists

Young scientists are leaving

Grants for PhD students have remained at the same level since 2013, while the cost of living has gone up. A lack of prospects is threatening to drive a generation of bright minds abroad or into a career outside science. ‘Companies are attracting researchers away from science with salaries that are slightly higher than the grants,’ says Michelle Picoli, a Brazilian postdoctoral researcher at UCLouvain in Belgium. ‘Some supervisors are begging PhD students to at least finish their dissertation before they leave.’ There are no statistics on the number of people emigrating or leaving the sciences, but Picoli is one of them. She and 14 others published a letter in Science to express their concerns. ‘I was working on a project at INPE, funded by the Amazon Fund. When the suspension of that fund was announced, I left for a new job in Belgium.’

Young scientists must learn to fight

Like Câmara, Picoli sees the job market at research institutes and universities shrinking. ‘In recent years there has been a sharp decline in vacancies for professors. Many of the positions of retired professors remain unfilled. That is one of the reasons why some former and emeritus professors continue to work. They do not earn more money by doing so, but do it out of dedication to science and society.’

Elections

Both Câmara and Picoli expect Bolsonaro’s presidency to end this year. Elections are due in October, with former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (Lula) standing as a candidate. Câmara emphasizes that scientists must take action. ‘Being hopeful doesn’t get you anywhere, but action does. Many institutes are repositioning themselves to influence the new government. The younger generation did not experience the dictatorship of 1964-1985. They have to learn to fight.’ Picoli agrees: ‘Researchers in Brazil see their scientific work as an act of resistance. The mentality is changing. They want to restore trust among the population by separating facts from pseudo-facts. For example, Brazilian scientists recently revealed that Dr Evaristo de Miranda’s research group works with questionable data and literature to sow discord around issues such as climate change and deforestation, with a big influence on government policy.’

Picoli hopes Lula wins, and then change will come. During his previous term, Lula invested in science and opened new universities. You don’t build up research budgets overnight, however, Picoli says: ‘They have been cut over several years and recovery will take at least five or ten years. Once they leave, young researchers will not return quickly.’ Câmara expects that a new government will soon replace the director of INPE. ‘It is a very prominent institute,’ he explains. ‘It would be a symbolic act, and people want high quality data for the new government’s policies.’

Science in Brazil has had its budget slashed during Jair Bolsonaro’s presidency. The Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (MCTI) has 66 per cent less to spend than it did in 2018. The budget of the Brazilian National Institute for Space Research, INPE (the Brazilian counterpart of NASA), was more than halved from 2020 to 2021. INPE is one of the main watchdogs on deforestation and changing land use in Brazil, using satellites to monitor the Amazon forest and the Cerrado savannah. Cuts in science are therefore a threat to nature conservation too.

Photo: Shutterstock

Photo: Shutterstock