Online and hybrid educational innovations have gained unprecedented momentum since Covid-19 appeared on the scene. The way students organize their studies also seems to be changing for good. Three WUR experts paint a picture of studying in the future for Resource, with four themes.

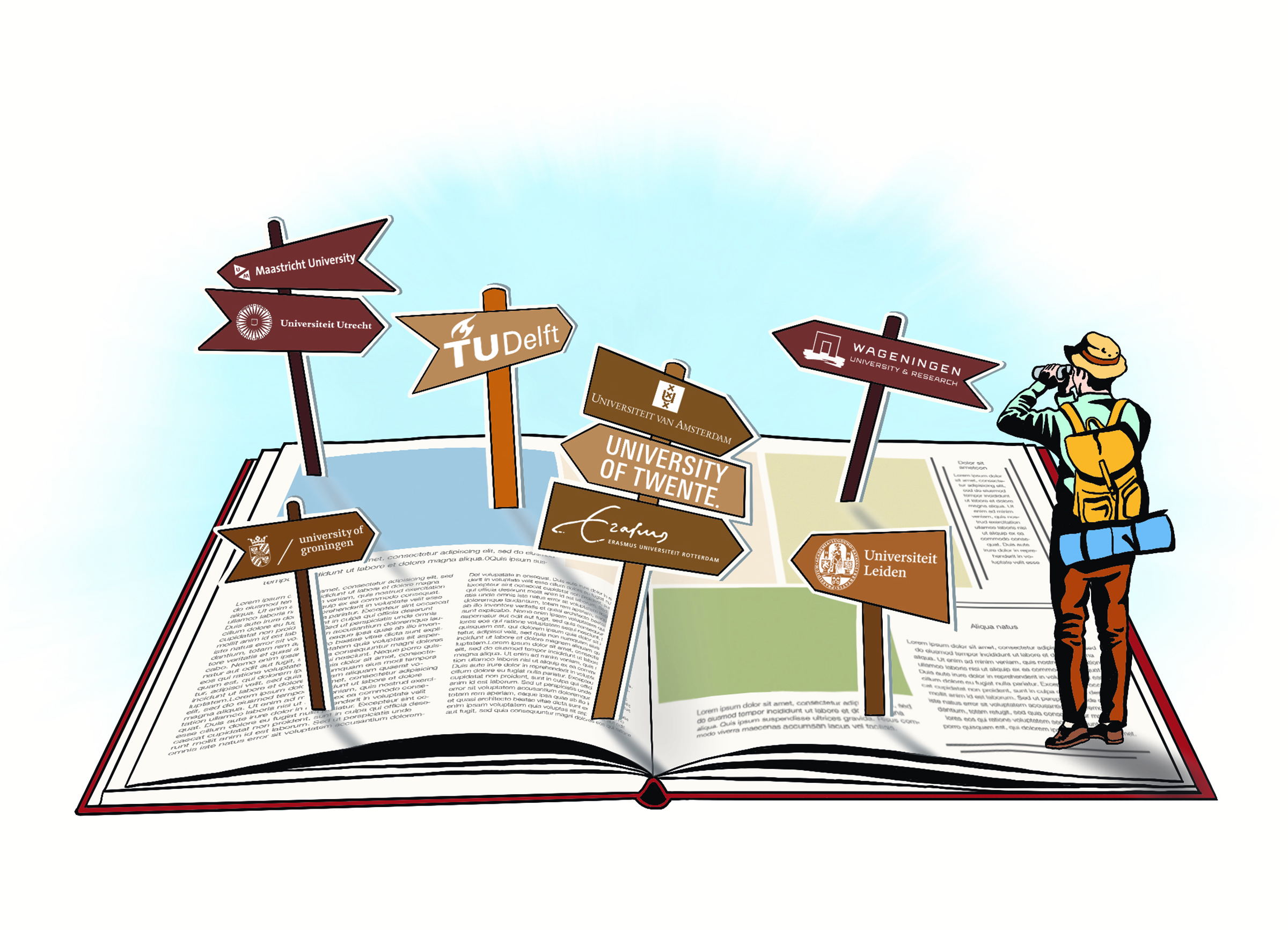

1. Tailor-made education – Lonely Planet Degree Guide

Instead of looking at whether you fit in as a student, you will soon be able to tailor your education to your requirements.

Current students already have a lot of choice as to which direction they take in their studies, says Erik Heijmans, head of WUR’s Education Support Centre. ‘For example, in the Master’s phase there is room for multiple electives and students can choose the topic of their thesis research, the Academic Consultancy Training (ACT) project they want to work on, and where they go for their internship. And many students also decide to do two Master’s degrees.’ So a student’s career can already be tailored to their personal preferences. The scope for tailor-made education will only increase, expects Ulrike Wild, Director of Open & Online Education at WUR. ‘You no longer check whether you fit in with the programme; you put together a programme that suits you. With a more flexible system, you can also facilitate learning paths that are more in line with today’s multidisciplinary issues.’

Heijmans: ‘You can make combinations with every discipline and every set of courses. By combining the themes of soil remediation and plant breeding, for example, you can create a customized learning trajectory.’ And it could be even freer than that, he says. ‘Make sure there is a firm foundation of compulsory elements, such as a thesis and a number of academic skills courses. The students can also design their own degree programmes. You can think up any combination at Wageningen. With the theme of food, for example, you can go in the direction of health, soils, technology, sustainability, production, logistics, and so on. In short, you can be innovative in how you combine disciplines .’ This does require coaching, says Heijmans. ‘To prevent someone from taking only introductory courses. That way you end up knowing a little bit about everything. Your studies do need to have focus and depth.’ Wild: ‘Ingrid Hijman inspired me with the concept of the Lonely Planet Degree Guide: a travel guide to our domains in which you as a student can map out your own route.’

Universities will also cooperate more between domains, Heijmans expects. ‘Delft has architecture, Wageningen has sustainability. Bring them together and you get sustainable urban development. That kind of crossover is the future. The rapid development of hybrid education in the Covid era is also making it easier for students to take courses at other universities. That was already possible, but it is becoming easier and easier.’

2. Lifelong learning (for everyone)

The standard path of three years on a Bachelor’s degree and two on a Master’s will end and professionals will return to the university during their careers for in-service training.

‘In the past, you did a Bachelor’s and a Master’s and then you were done,’ says Professor of Education and Learning Sciences Perry den Brok. ‘That is no longer the case. Your degrees are a starting point, but learning doesn’t stop when you have finished your Master’s degree. The government is going to create personal budgets for lifelong learning.’

Den Brok expects that increased use will be made of ‘badges’ and ‘microcredentials’. ‘Microcredentials are when you follow parts of a recognized programme, for which you can receive a partial certificate or partial diploma. Badges indicate the level to which you have mastered certain skills. Before long, the courses you have taken will be listed on the front of your certificate, and on the back will be the skills level you have attained in, say, leadership skills, entrepreneurship, and so on. You might also postpone part of your Master’s programme until later in your career. Maybe halfway through your Master’s degree you have enough skills to start a good job, and postpone the rest of your studies until later. Very useful, especially if there will soon be national or international standards for badges. Then a record will be kept centrally that you have done everything that comes under level 1 of a skill. Other universities and companies will see that, and you can also show on LinkedIn that you not only know a lot about forestry, but also that you have certain skills.’

Lifelong learning also means that people are returning to university later in their careers for further education, says Ulrike Wild of Open & Online Education. ‘So more people will study part-time alongside a job. Perhaps they will spread their studies over a longer period of time, alongside their career. I think that everyone will soon have a kind of personal “wallet” or portfolio that lists what they have studied, how much education budget they have left, and what education they have access to. Then you carve out your own personal learning path throughout your life. That also takes the pressure off you to constantly make the right decisions: you learn now what you need now. The courses you take are like building blocks.’

If people return to university throughout their careers for further development and training, the makeup of the student population also changes, says Den Brok. ‘A new group of students is added to the current Bachelor’s, Master’s and PHD students. How will this new group, the professionals, be taught? Will they just sit in the classroom with regular students? For some courses this will work and even have its advantages, but not for others. So we need to think about which education we make available to working people, and in which way, and whether they will take lessons together with students. You can’t just throw everything open to everyone. So: find out what the need is and then make targeted choices.’

If you take the concept of microcredentials to its logical conclusion, it could also have consequences for who gets access to university. In the Netherlands at present, you have to have a high school certificate (VWO) or be a graduate of a university of applied sciences. Wild: ‘Perhaps it will soon be possible for people who have completed an intermediate vocational education (MBO) course and have specialized in electronics to take a few courses at university to further develop their skills in that field. Then you won’t get a full degree, but you will get those microcredentials.’

3. Stretch students with real-world challenges

Education needs to get more active: no more lecturing to big groups with a few questions at the end, but putting students to work on assignments in the real world.

Den Brok, Wild and Heijmans agree that lectures – in the classic sense of the word in which students sit and listen – are past their sell-by date. Heijmans: ‘Students should not be passive consumers of education, but active participants in challenging, highly cognitive assignments that require knowledge. In Wageningen, we often pamper students to make sure they get to the finish line. If you activate them by having them work on a practical problem, they have to actively look for the relevant knowledge themselves. Knowledge acquired that way is more likely to stick. I can give a lecture on chemistry, but I can also say: here is a fire extinguisher, find out how it works. Then students end up learning about chemistry themselves. A student chooses a degree programme out of enthusiasm or fascination, so they need you to challenge them.’

Through Academic Consultancy Training (ACT) projects, student challenges, internships and their thesis research, WUR students already work on practical projects on a regular basis. ‘But it would be good if more courses like ACT were introduced into the Bachelor’s programme,’ says Heijmans. There is a tremendous increase in interest in learning through challenges, Wild observes. ‘That is because of the multidisciplinary aspect: students from different programmes work together on complex assignments. The human race is also facing challenges that cannot be solved using one isolated discipline.’

But in Den Brok’s view, this does not mean that the university will be more geared to hands-on professional education. ‘Academic values and depth will remain important. But the problems of the future demand more than academic skills. We need creative thinking, entrepreneurship, the ability to cooperate with people from other domains, and so on. At the moment, universities still primarily train their students to be researchers, but by no means everyone becomes a researcher. University graduates are also needed in companies, social organizations and in politics. These things call for different profiles and skills. Challenge-based education helps to develop those skills.’

4. New apps and VR

New apps and virtual reality (VR) are becoming increasingly important during fieldwork and as preparation for or replacement of practicals.

There have been some notable digital innovations in the field of education in Wageningen recently. For example, Bauke Albada (Organic Chemistry), Harry Bitter (Biobased Chemistry & Technology) and Han Zuilhof (Organic Chemistry) developed a virtual reality (VR) app with which students wearing VR glasses can practise building their apparatus and performing a complex distillation.

‘These kinds of innovations do not replace the real thing in every case, but they can enrich the learning experience,’ says Den Brok. ‘You practise with lab skills before you set to work for real. We have also tried it out in teacher training: maintaining discipline in a digital classroom with VR glasses on. It is still experimental at the moment, but the better the technology gets, the more complex you can make it.’ Heijmans sees opportunities in the VR field too. ‘At VU Amsterdam University, they use VR to see how joints move in a 3D situation. If you cut open a dead animal, it no longer moves. Using VR for this means fewer dead animals and a simulation may even show how it works more clearly.’

Since the Covid period, the Peek educational app has been in use increasingly often too. This app from Wageningen was devised by Teun Vogel (Soil Physics and Land Management) to make fieldwork more fun and educational. Heijmans is enthusiastic. ‘Instead of trotting along behind the teacher, you go out into the field with a task to solve. Then it is still good to have a teacher in the field, because the inspiration is important, but their role changes: from a sage on stage to a wise guide on the side.’

Dies Natalis on the future of education

The theme of WUR’S 104th Dies Natalis (Founders’ Day) this year is ‘Metamorphoses, shaping tomorrow’s education’. The keynote speaker at the ceremony on 9 March, Dirk van Damme, says in an interview on wur.nl: ‘I think that Covid brought about a tectonic shift in the way we look at education and how it should be offered. There is going to be a much greater integration of digital and distance learning in regular education.’ Until the end of May 2021, Van Damme was Senior Counsellor at the Directorate for Education and Skills of the OECD in Paris. He will give a presentation on developments in and the future of education.

The expectation is that soon you can tailor your degree programme to your personal preferences. You will have a kind of Lonely Planet Study Guide that lets you plan your own student journey. Illustrations: Valerie Geelen

The expectation is that soon you can tailor your degree programme to your personal preferences. You will have a kind of Lonely Planet Study Guide that lets you plan your own student journey. Illustrations: Valerie Geelen