People without a Covid-19 vaccination might not be allowed into bars or on planes, suggested minister of Health De Jonge. Would that amount to compulsory vaccination in disguise? No, says WUR ethicist Marcel Verweij. ‘It could motivate people to get vaccinated, but I see that as a positive side effect.’

Various polls have shown the number of people planning to get a Covid vaccine hovering around 70 per cent. The question is whether that will be enough to protect the whole country. The minister of Health, Hugo de Jonge, recently suggested that when the Covid-19 vaccine becomes available, people who get the vaccine will be able to return more quickly to ‘the old normal’. Those who do not get inoculated might not be allowed to attend events or go to a bar, for instance. That comment rubbed a lot of people up the wrong way, who thought it smacked of covert compulsory vaccination.

Allowing more freedoms to people who have been vaccinated is entirely justifiable, according to WUR ethicist Marcel Verweij. He maintains it bears no comparison to compulsory vaccination. Verweij is a professor of Philosophy and for years was a member of the Health Council of the Netherlands’ Vaccinations Committee. ‘As a human, you have a moral duty to take responsibility and help prevent the spread of the virus. We’re already taking on that responsibility: we don’t shake hands, we keep our distance, wear face masks, get tested and go into quarantine. Various measures restrict our freedom and some of those are imposed on us, like the temporary lockdown. Such measures are justified because they help prevent the spread of the virus. But if you get vaccinated, those restrictions will no longer be necessary.’

Freedom

To what extent should the government be allowed to limit people’s freedom? ‘Restrictions on freedoms should be proportional. That is, no more severe than what’s strictly necessary to achieve the goal. You always have to weigh individual freedoms against the public interest.’ Our individual freedoms are secured by the constitution, which guarantees every person the right to self-determination. That includes the right to decide what medicines are put in their body. Verweij: ‘That’s true, but constitutional rights are not absolute. Freedoms can be limited if doing so prevents harm to others. Both the constitution and the European Convention on Human Rights stipulate under which conditions it is justifiable to curb those freedoms. One example is protecting public health. A policy that relaxes certain regulations for vaccinated people can be justified if the vaccine is available to everyone and, even more importantly, if it is clear that vaccination will prevent the spread of the virus and lead to group immunity. Incidentally, we don’t know for sure that the latter is true for the Covid-19 vaccines.’

Nobody will be forced into it, and those who refuse the vaccine won’t go to prison

Indirect

Verweij thinks the phrase used by De Jonge – ‘indirect vaccination obligation’ – was an unfortunate choice. ‘Nobody will be forced into it, and those who refuse the vaccine won’t go to prison. That does happen in Belgium, for instance, to those who refuse to vaccinate their children against polio. That really makes vaccination compulsory. For Covid there won’t be anything like that – the only coercive element is in the quarantine measures. If the vaccine proves effective at preventing infections and reduces the risk of infecting others, it will offer us another opportunity to take on responsibility for protecting each other. Existing measures like quarantine would then become unnecessary and people who have had the vaccine could get more freedom of movement.’

Vaccination offers us a chance to recover more freedoms

According to Verweij there is another argument. ‘Limits on freedom have to be proportional. If someone who has had the vaccine is forced to quarantine despite not being infectious that would be disproportionate and ethically indefensible.’

Consequences

Verweij thinks we should not see this as a punishment or reward. ‘We’re now in a situation where there are strict rules. Vaccination offers us a chance to recover more freedoms, because it would eliminate the need to stick to other precautionary measures. If getting vaccinated means that you no longer have to quarantine at home, you’re still free to refuse the vaccine. The compulsory part is the quarantine, not the vaccine. There’s no question of obligation, covert or otherwise. The same applies to airline companies that require people to show proof of vaccination. It might motivate people to get vaccinated, but I see that as a positive side effect, not as a means of compulsion. You’re free to choose not to get the vaccine, but freedom also means that you have to accept the consequences of your decision.’

Compulsory jabs for the Netherlands?

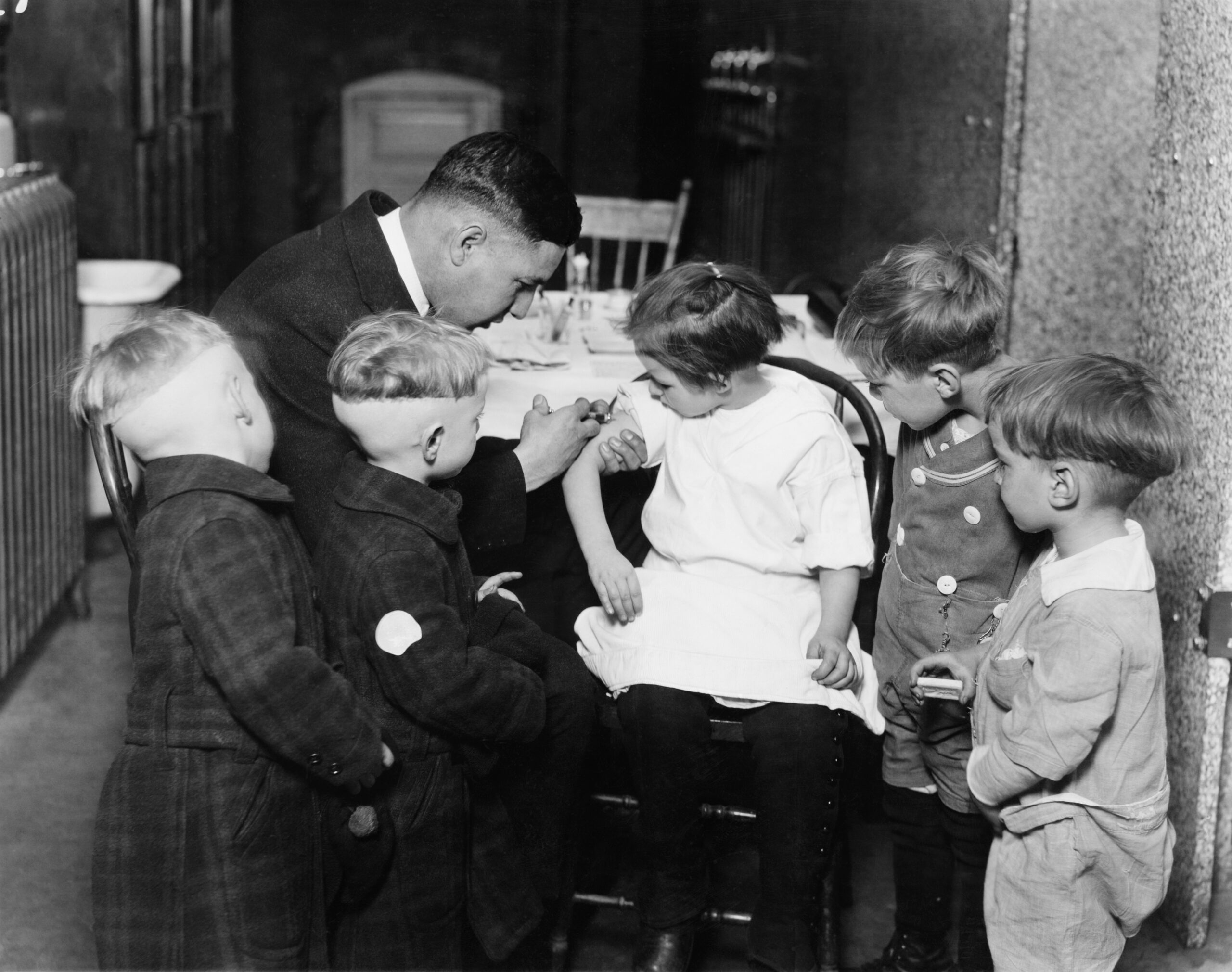

At the start of 2019—well before the Covid-19 crisis—the World Health Organization identified ‘vaccine hesitancy’ as one of the biggest global threats to public health. Is that not a reason to make it compulsory? ‘Those cases are primarily about vaccination programmes for children, where there are stronger arguments for a vaccination obligation,’ says Verweij. ‘That’s because the child isn’t the one refusing the vaccine. The government has a duty to protect vulnerable children, sometimes even against the wishes of the parents. The Netherlands is one of the few countries in the world where vaccinations are not compulsory. At a minimum, most countries demand that children at nurseries and schools are vaccinated.’

Photo: Shutterstock

Photo: Shutterstock