Thus discovered Milou Santbergen, who obtained her PhD in Organic Chemistry on 17 November.

Currently, early-stage testing of new medications or the effect of certain foodstuffs is conducted in-vitro (cells in Petri dishes in a lab). However, it is now also possible to make organs on a chip: a miniature model of the organ. ‘The advantage being, that it is more representative than individual cells’, says Santbergen. ‘For example, you can emulate the flow of food through an intestine. However, it is also more complex and labour intensive to work with.’

Automatic

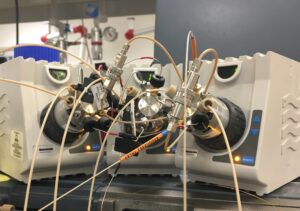

Santbergen combined an intestine on a chip with a super-advanced mass spectrometer: a device that identifies materials by their mass. This way, she can analyse online how medication or poisons move through the intestinal membranes. ‘This process is fully automated, which is an advantage’, Santbergen explains.

You can start up the equipment, and go have some coffee. This makes it much less labour intensive and leaves no room for human error. Moreover, collecting data is much faster, something that would typically take two days is now completed in a matter of hours. And, because the measurements are real-time, you can also measure materials that are unstable, and that would have disintegrated if you were to measure afterwards.’

However, to get here, there were some hurdles that needed to be taken. ‘An intestine on a chip is not so much a chip, as a complex set of liquid tubes linked together and attached to the measuring device. In the beginning, we had leakages, and I often felt like a plumber.’

I often felt like a plumber

Milou Santbergen, PhD candidate Organic Chemistry

One purpose of these organs on chips is to use them to replace animal testing in the future. Santbergen: ‘The great thing is that this link with mass spectrometry has now been tested in a model intestine, but it will work just as well for a skin model or liver model. So, there are many possibilities.’

Replacing animal testing

For the time being, however, it remains an academic development. According to Santbergen, more focus on the validation of these methods is needed. ‘Everyone is busy developing their own chip model, but when they’re done developing, they move on to something new. Validation is needed to determine whether this works better than animal models. That is not done enough. Validation research may not be as sexy, but lack thereof prevents real developments.’

Photo: Shutterstock

Photo: Shutterstock