Insects like crickets communicate through sounds. During evolution, these animals have developed specialized hearing and sound-producing organs. Researchers performed an extensive study to understand how this hearing, and sound producing, evolved and how it affected diversification in insects of the order Orthoptera, which includes species such as crickets, katydids and grasshoppers. They found that this evolved primarily to avoid predators, and was later also used to find a mate. They published their results in Nature Communications.

When, what and how

‘While many studies have focused on how insect sound communication works, we don’t know when, how and in what context hearing and sound-producing organs evolved in the first place’, says Sabrina Simon, assistant professor of Biosystematics. There were two main theories on this.

By tracing back their history we could figure out that acoustic communication evolved about 300 million years ago

Sabrina Simon, assistant professor of Biosystematics

For sex or security?

Hearing might be an adaptation for detecting and escaping predators. And, possibly later, this was also used for sexual signalling. ‘That would mean that the evolution of a hearing organ preceded that of the evolution of a sound-producing organ’, says Simon.

Another option is that hearing, and sound-producing organs have co-evolved at the same time, as a way to find a mate for females (hearing), and to attract a mate for males (sound production). This has been suggested for cicadas, crickets, and katydids. Simon: ‘If this is the case, we would expect that both hearing and sound-producing organs can be traced back to a single common ancestor.’

300 million years ago

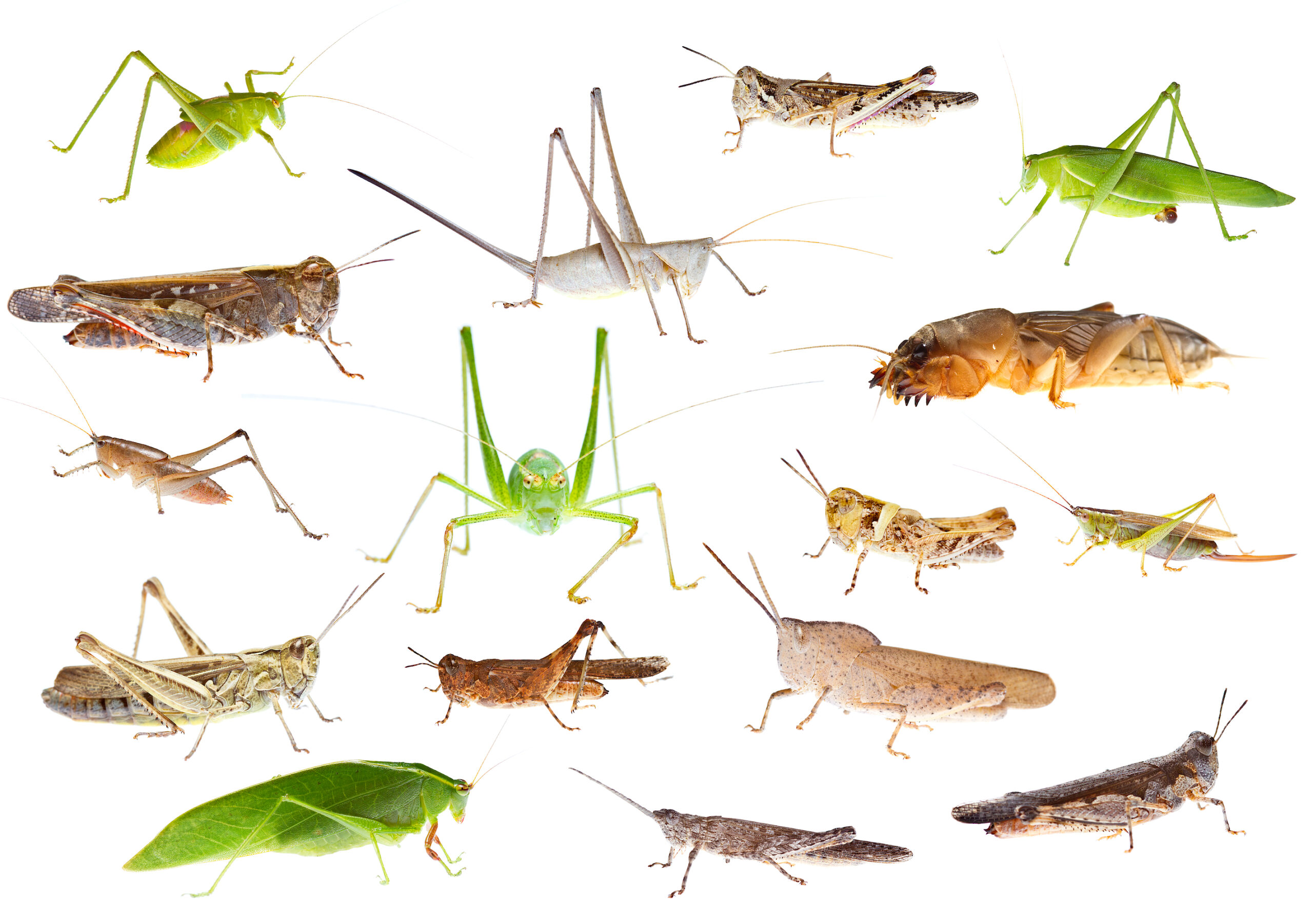

The researchers concluded that the first scenario was the case. They discovered this by reconstructing the entire family tree, using genomic data and fossils of the insect order Orthoptera, which includes over 27 thousand species. Within this group, some species use sound for predator defence, while others use it for sexual attraction. And some of the species cannot hear or produce sound at all. ‘By tracing back their history we could figure out that acoustic communication evolved about 300 million years ago as a predator-defence mechanism and that later some species also started using it for sexual signalling’, says Simon. ‘Also, insects were the first animal species to develop acoustic communication’.

Role of sexual selection

The research opens new doors for further research. Simon: ‘The Orthoptera-tree that we constructed could be used as a tool to study the evolution of other traits, for example, diet and diet shifts, behaviour, and wing evolution.’ On the other hand, this research also disproves an important theory. ‘There is a huge number of insect species, but not every group is so successful or species-rich as Orthrotera’, says Simon. ‘Already, Charles Darwin considered sexual selection as one of the evolutionary forces causing speciation and consequently, diversity. A variety in cricket sounds and different preferences by the females could have driven reproductive isolation and therefore speciation. But we found that Orthoptera groups using sound as a sexual trait, do not show higher diversity rates. So, sexual communication cannot be responsible for the huge number of singing species, and there are other major key innovations responsible for this astonishing diversity.’

Orthoptera collage. Corné van der Linden (MSc student Biosystematics Group)

Orthoptera collage. Corné van der Linden (MSc student Biosystematics Group)