Until a few years ago the idea of wolves in the Netherlands sounded utopian. But since the first wolf was sighted in March 2015, things have moved quickly. And the high point so far was the pair that were snapped by a camera trap on the northern Veluwe early in May. A male and a female wolf together. So we’ve got the wedding photo; now all we have to wait for is the children. The first since the wolf disappeared from the Netherlands in 1869. For ecologists, the arrival of the wolf is something to celebrate. But others, particularly farmers, see nothing to smile about. They think the Netherlands is too small for the ‘big bad wolf’. So what are we to do with this wild animal? Resource asked an ethicist/ philosopher, a social geographer and a cultural geographer from WUR. With a hunch that it won’t be nature’s carrying capacity but human tolerance that will decide whether the wolf is made welcome.

‘A wolf in the Oostvaardersplassen is fine, but he shouldn’t stand outside Lidl’ – Berenice Bovenkerk, animal ethicist and environmental philosopher

MYTH FORMATION

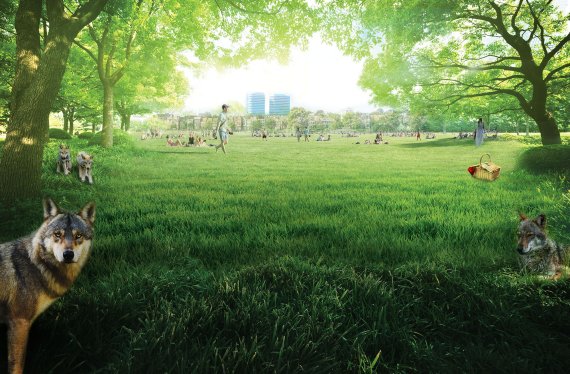

We have uneasy feelings about the wolf, says animal ethicist and environmental philosopher Bernice Bovenkerk to kick off with. She studies people’s ideas about nature and the changing relationship between humans and animals. ‘The wolf is “discomforting wildlife”, as the Nijmegen scientist Mateusz Tokarski described it in 2017 in his thesis Wild at Home. And I agree entirely. The prevailing thinking is that we should take animals into consideration but the fact is that wild animals can also be inconvenient. We are strongly inclined to put things in boxes. There are domesticated animals and there are wild animals. And wild animals must not intrude on our space. A wolf in the Oostvaardersplassen nature reserve is fine. But if it is suddenly standing by the entrance to Lidl, that’s a different matter. Then it crosses a boundary. It is somewhat comparable with the discussion about genetic modification, where another red line is crossed for a lot of people. And we feel uneasy about that.’

Fear plays a big role in this, says Bovenkerk. ‘The boundary is related to fear. And to the myth around the wolf. The wolf was wiped out in the Netherlands 150 years ago because it came too close and devoured our sheep. That’s an issue again now. But if you look at how many sheep are killed by wolves, and how many by foxes and dogs, the fear is excessive. The wolf is really not a danger to humans. So there is obviously something else going on here.’

‘They are said to eat babies, but who leaves babies behind in the woods?’ – Maarten Jacobs, cultural geographer

EATING BABIES

‘What I find striking about the wolf discussion is the number of statements made without knowing whether they are true,’ says cultural geographer Maarten Jacobs. ‘About our fear of the wolf, for instance. Who is afraid, and what are we assumed to be afraid of? Yes, wolves kill sheep: that is true. But you hear the craziest things. That they eat babies, for instance. It makes me wonder who leaves babies behind in the woods.’

In his work, Jacobs studies images of nature and how people relate to animals and the landscape. He recently became an advisor to the Wolves in the Netherlands alliance. ‘I had criticized their website in a lecture. It starts with the fear of wolves and then explains why we don’t need to be afraid of them. The implicit message at the end is: if you are still scared of wolves now, you’re really a bit stupid. Well, that’s how not to go about it.’

Jacobs thinks you should take fear seriously. ‘Otherwise you get polarization, as we are seeing in Finland now. There the wolf has become a symbol of the opposition between groups: a kind of currency in the us-and-them discourse of city versus country, nature-lovers versus hunters. At some point, the conflict is about those clashing interests rather than the wolf itself. Then you’ve got a real problem. In Finland they are holding protest marches against the wolf. We’re not getting that here yet, but the discussion does seem to be heading in that direction.’

‘The Dutch are so naïve in the way they behave around wild animals’ – Birgit Elands, social geographer

NOT TOO CLOSE

It is not surprising that fear plays a role in the wolf debate. After all, we all grew up with Little Red Riding Hood, The Wolf and the Seven Goats, and songs and games which make the wolf the ‘baddie’. Yet fear doesn’t influence our behaviour all that much, according to social geographer Birgit Elands. This was seen in research she did in 2012 on risk perception in relation to the arrival of the wolf. ‘Most people at that time considered encountering a wolf an acceptable risk. Except if they were to meet the wolf in their own back gardens. The wolf shouldn’t get too close: that is the crux of the matter.’

One year previously, Elands got Bachelor’s students to conduct a survey in two residential neighbourhoods of Nijmegen. ‘Slightly over half of the respondents were in favour of the wolf coming here, one third were neutral and a few were against.’ But at that point not a single wolf had actually been seen on Dutch soil. ‘Last year, my students did the same survey in the woods of the Speulderbos, the hunting grounds of the wolf pair seen now. This time, 45 per cent were against the coming of the wolf. And of course, this is just a small study, and it was done in the woods and not in the city. Many of the respondents were elderly, whereas young people generally tend to be in favour of the wolf. But still…’ Eland plans to repeat the survey in the Speulderbos. This time, on request of the forest ranger, local residents will be questioned.

EVOLUTIONARY EXPLANATION

Jacobs confirms that people’s wolf-friendliness is not a given, and that it depends on how close the animals get. ‘Research in our neighbouring countries snows that attitudes are at their most positive before the wolf arrives in an area. And that tolerance decreases once it has arrived.’

Jacobs has done some research of her own among students, looking at emotions in relation to the wolf. ‘Of the positive emotions, the highest scoring was pleasure. Of the negative emotions, it was fear. But fear varies a lot – from a bit scared to really terrified. But what exactly are you measuring in this kind of self-assessment? Do people know themselves how frightened they are? Are they aware of their fear?’

From an evolutionary point of view, the fear of large predators is explicable, says Jacobs. ‘But that has never been confirmed by research. Fear is seen as an inborn basic emotion. But you cannot deduce that from existing empirical research. We can demonstrate that something elicits attention – “arousal” – and that people ascribe value to it – “valence”. But there isn’t a physiological set of reactions that is specifically linked with fear. In that sense, fear is an interpretation of physiological reactions.’

UNCONTROLLED

According to philosopher Bovenkerk, fear is actually part of the value of wild animals. ‘A lot of people value that scary, uncontrolled side of wild animals. Going out into nature is a way of reacting against everyday life, and feeling one with nature for a while. It is part of the experience of nature that you might encounter animals that you cannot control, and that you can feel small yourself for a moment. And that doesn’t have to be a pleasant experience, but it is part and parcel of your idea of nature. That is where the contrast lies between the wolf’s supporters and its opponents. Supporters value that uncontrollable aspect of the wolf, whereas opponents say we don’t have any wild nature in the Netherlands and we shouldn’t aim to have it either.’

WAITING FOR TROUBLE

On the question of whether the Netherlands is ready to live alongside the wolf, Bovenkerk is pessimistic. ‘Look at what happened in the Oostvaardersplassen, and how we have treated the game there. I am very disappointed in that.’ Elands is apprehensive too. ‘It is very easy to say the wolf should be welcome from your armchair, so at a distance. But I am afraid there will be trouble sooner or later. That it won’t be a sheep but a dog that gets killed. A lot of people let their dogs off the lead in the woods. And the Dutch are extremely emotional about their pets. I think all it would take is for something to happen, and a huge emotional discussion would break out. And however small the chances of that are, it is sure to happen eventually because the Netherlands is a densely population country. The Dutch are so naïve in the way they behave around wild animals.’

You should take fear seriously, otherwise you get polarization

Maarten Jacobs – cultural geographer

‘The big question, if you ask me,’ says Jacobs, ‘is how we treat people who are bothered by the wolf. Okay, there are compensation arrangements in place, but is that sufficient? And even if there is compensation, it is not a sheep farmer’s aim to supply wolves with food. So the problems are not solved by good compensation arrangements. As for fear: you need to avoid making people feel they are not respected. You should frame the message that there is nothing to be afraid of differently. Acknowledge the fear: it’s understandable that you are afraid, although it is not strictly necessary. In Finland they did research on whether you could reduce fear of bears by taking groups of people on trips to see bears. The bears are chipped, so the guides know exactly where to find them. But of course you can’t take everyone out on wolf-spotting trips.’

HOSTILE

The first Dutch wolf cubs have not been born yet – or have not been spotted, at least. But both the friends and the enemies of the wolf agree that it is only a matter of time. What is certain is that they will be born into a partly hostile world, where by no means everyone will welcome them with open arms. Then again, the wolf is used to that. Has it ever been any different?

| Year | TIMELINE- THE WOLF IN THE NETHERLANDS |

|---|---|

| 1869 | Last wolf in the Netherlands killed near Schinveld (Limburg). |

| 1982 | The Convention of Bern makes the wolf a protected species. |

| July 2013 | A dead wolf is found near Luttelgeest (Flevoland). It turns out the animal was put there; it was shot earlier in Eastern Europe. |

| March 2015 | A live wolf is spotted in the Netherlands for the first time since 1869.It roams around Drenthe and Groningen provinces for a few days. After this, sightings follow one another in quick succession. |

| March 2017 | A wolf is run over and killed on the A28 in Drenthe. |

| February 2018 | A wolf wanders through the streets of Bennekom and Veenendaal at night. |

| February 2019 | Female GW998f stays on the northern Veluwe for more than six months. That means the wolf has officially settled in the Netherlands. |

| April 2019 | The first wolf pair is captured on camera on the northern Veluwe. |

| 2019…? | For the first time in one and a half centuries, wolf cubs are born in the Netherlands. |

WOLF CAPTURED ON CAMERA IN DRENTHE

Click here for the video fragment of the wolf in Drenthe (Credit: Staatsbosbeheer).

Photo: Hugh Jansman

Photo: Hugh Jansman