Every year, a teacher is elected ‘Teacher of the Year’. Ignas Heitkönig (Wildlife Ecology and Conservation) held that title for a year. Resource interviewed him on his time as a student and the road to teaching.

What did you want to become as a child?

‘I was born in the Catholic city of Sittard in 1957. I had trouble accepting the huge difference between rich and poor from an early age. As a young teenager, I considered becoming a Franciscan monk, otherwise known as the Friars Minor, due to their modest lifestyle.’

You came to Wageningen to study Biology in 1975. What was your student life here like?

‘Biology was one of the toughest programmes. I was a good student, but there were many distractions. I joined SSR rather than the catholic student’s association KSV, as I felt their main purpose was drinking a lot of beer. I failed my first year and considered switching to studying Physiotherapy because that, too, would enable me to help people. Yet I decided to give Biology another shot. This time, I passed. I went on to choose as many tropical courses as I could, ranging from tropical plant breeding and animal husbandry to tropical soil science. I saw myself as an idealist and wanted to move to the tropics to help make the world a better place.’

You did your internship in Mali. What work did you do?

‘Back then, the region was frequently affected by droughts, resulting in famines. The study focused on the question of whether humans could use wildlife instead of cattle as a protein source. It was exciting and nice work, and I got along well with my supervisor Steven de Bie, so I decided to graduate on the project. I began to study the roan antelope’s diet by gathering and analysing its manure. Roan antelopes have dry manure, somewhat similar to sheep droppings. By treating it with nitric acid, it can be analysed under a microscope to determine what plants they eat. Today, you would simply enter the data into an AI system, but things were different back then. I designed a determination key that was later used by other students to determine plant species in the manure of other West-African animals.’

And you ended up in South Africa.

‘De Bie and I met Norman Owen-Smith at a conference in Finland: A South African looking for a doctoral candidate to study roan antelopes − the very species on which my manure study was based. Owen Smith wanted to know why roan antelopes thrive so well on nutrient-poor soils while other large herbivores, such as zebras, don’t do nearly as well. Terribly interesting, but I also thought: South Africa, Apartheid, no way. It was at odds with everything I valued. I recall roaming the rainy streets of Helsinki for hours pondering whether or not to accept. It was an impossible choice.’

But you went.

‘Someone in Wageningen said: If you go, you may be able to alleviate some of the pain Apartheid inflicts. I took the decision and hopped on a plane. My university was an anti-Apartheid university that was at odds with the government, and I quickly felt at home in this world where everyone hated the system of Apartheid.’

I mimicked teachers that I had enjoyed learning from as a student

Ignas Heitkönig, teacher Wildlife Ecology and Conservation

How was your PhD research?

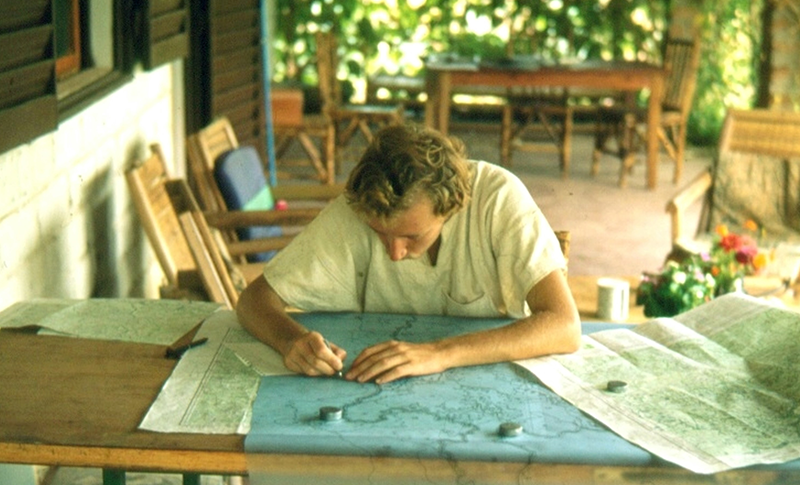

‘It was an interesting study with fieldwork at a two hour drive from Johannesburg. There, a herd of roan antelope lived on nutrient-poor soil. Some of the antelope were tame, so I was able to observe them from a short distance and see what they ate. Still, the research had its ups and downs. I didn’t get along very well with my supervisor, and the PhD trajectory was quite old-fashioned. When my grant was spent, my dissertation was not yet completed. To make ends meet, I took a teaching position at Venda University. The department head there felt that my expertise in roan antelope qualified me to teach a second-year course in animal physiology. I bought books and dived into the deep end.’

And just like that, you were a teacher.

‘Yes, although it was small-scale with groups of no more than fifteen students. Designing experiments with worms, mice and insects. I mimicked teachers that I had enjoyed learning from as a student and colleagues I had observed in Johannesburg. Someone told me that no matter how many pedagogical tricks you have up your sleeve, igniting the students’ enthusiasm is the best thing to aim for. It was a fantastic experience.’

Why did you return to the Netherlands?

‘I had married a Dutch nurse who worked with malnourished children. We had a beautiful but also difficult life. It was difficult for my wife to repeatedly see undernourished children trapped in poverty. So when my former supervisor De Bie contacted me at the beginning of the nineties to let me know that his position as professor in Wildlife Ecology was to become vacant, it was a golden opportunity. I had worked on the dissertation during my holidays and had almost completed it. I applied, and much to my surprise, I got the job. And so, I returned to Wageningen after ten years in South Africa. I did not become a monk but a teacher. My love for nature and concerns over injustice have remained.’

Want to learn more? We also interviewed Ignas Heitkönig on the topics of activism, outdoor teaching, bringing the A12 climate protestors cake and a tram line to Ede. Click here to read all about it.

Foto Guy Ackermans

Foto Guy Ackermans