In the Middle Ages, scribes and illustrators worked on parchment. Modern genetic and protein analyses reveal the biological secrets of these animal skins.

Plant sciences researcher Elio Schijlen had never heard of biocodicology until a couple of years ago. Now, he can justifiably call himself a budding biocodiologist – someone who uses biological techniques to study the material properties of old manuscripts (codices, the plural of codex). It was his expertise in molecular biology and genetics that took Schijlen on this new path exploring medieval art.

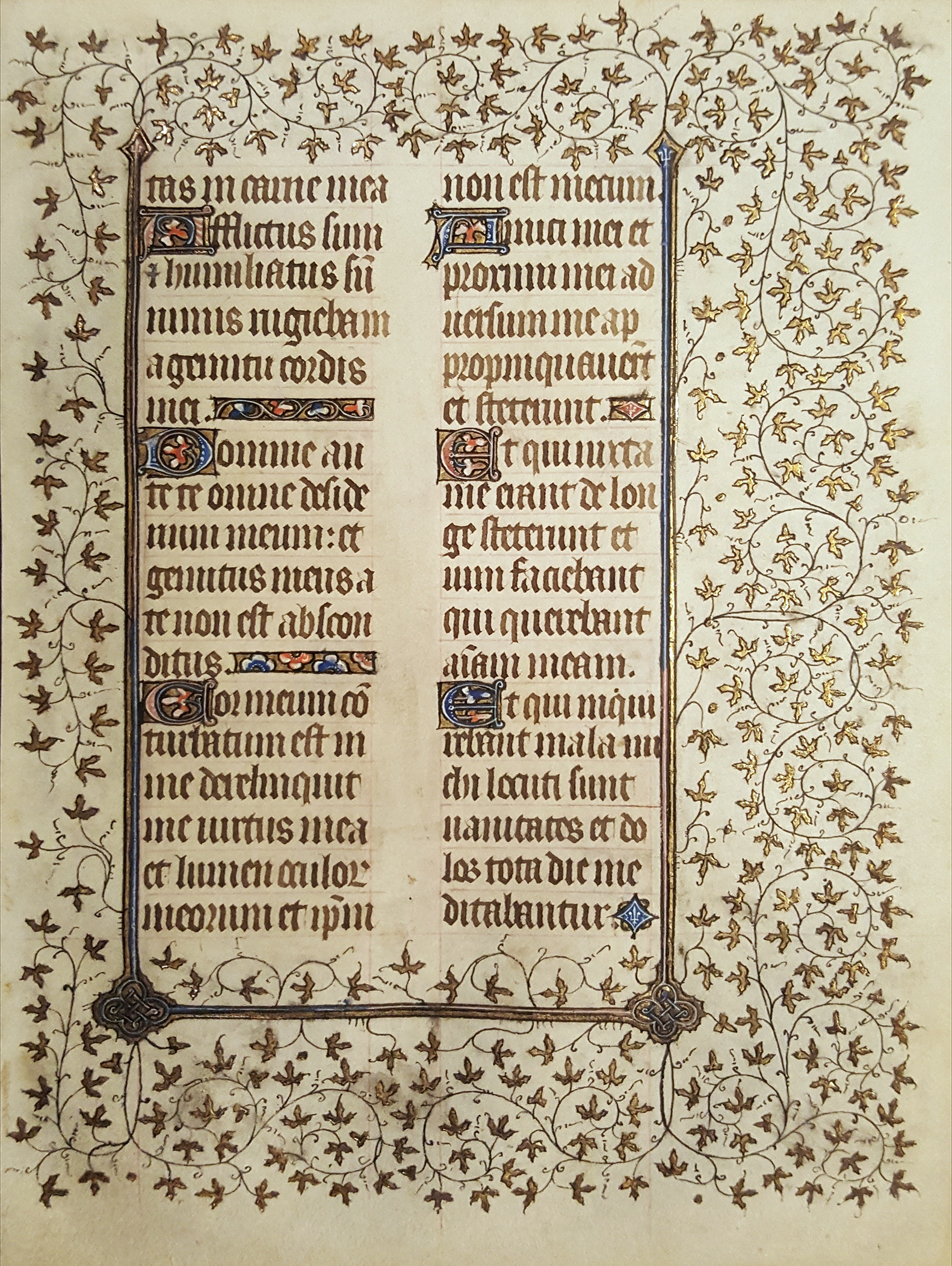

It all started with a question from the Maelwael Van Lymborch Studies foundation in Nijmegen. This is the centre for academic scholarship on the Van Lymborch family of artists. The brothers Herman, Johan and Paul van Lymborch are sometimes called the Rembrandts of the Middle Ages. The foundation asked Schijlen whether he could examine various parchments that are part of a medieval codex linked to the three brothers (see inset on Master B). Schijlen is the head of the Plant Sciences DNA sequencing facility, which deciphers genetic codes. ‘The foundation wanted to know whether we could use that technology for the analysis of medieval parchments, for example to find out what animal was used to make the parchment,’ explains Schijlen.

In principle, you might come across DNA from any living thing that has touched the parchment over the centuries

The request resulted in a project funded by the Dutch Research Council and the Nijmegen foundation, with Naturalis and Radboud University involved as well.

‘Until recently, studies of old manuscripts mainly looked at the author’s handwriting,’ continues Schijlen, ‘and physical properties of the parchment such as the texture, the ink and the paint. Genetic analysis can provide new, additional information, such as the animal used to make the parchment, its sex and possibly data on the breed or geographical origins. This can then be used to determine the relationship between different sheets of parchment. What is more, moulds and bacteria tell us about the state of the parchment. Such investigations were impossible until recently as the technology was not sufficiently advanced. Anyway, the extraction of protein and DNA would have been destructive, which is of course unthinkable with such historically and culturally valuable objects.’

Rub off

The technology and science have advanced so rapidly that these biological analyses are now possible. Schijlen and his colleagues were given the opportunity to take samples from nine sheets of parchment, taken from medieval books in different collections: the three sheets that the project was about and as a reference several sheets from the Kasteel Huis Bergh collection and from a private collection. The analysis focused on traces of DNA and the protein collagen. Either can be used to reveal which animal provided the parchment.

Parchment is made from the hides of farm animals.

Alles wat in en op het perkament in de loop der eeuwen heeft geleefd, kun je in principe terugvinden

That hide is largely made up of the protein collagen, the composition of which varies with the species. Schijlen obtained the protein by literally rubbing it off from the surface. This method is non-destructive and does not harm the parchment. The same cannot be said for the extraction of the DNA. ‘We needed to cut off a tiny piece of parchment for that. This would usually be impossible for an old codex because you are damaging the book.’

The protein analysis involved determining sequences of amino acids, the protein building blocks. The composition of amino acids is a characteristic of the species. In the analysis of the DNA, thousands of sequences of short fragments were compared against reference genomes for cows, sheep and goats. Schijlen: ‘Many fragments are identical for the three species, but you still see that a sample can have far more matches for one of them.’

Cowhide

The genetic analysis revealed large differences between the parchments. Those are differences in the genetic history, says Schijlen: ‘In principle, you might come across DNA from any living thing that has been in or on the parchment over the course of the centuries. That includes insects, pollen and microorganisms that landed on the parchment, and the people who held it. Those genetic traces are basically a kind of fingerprint of what has happened to the sheet over time. One of our conclusions is based on that and shows that some parchments are more closely linked because they share the same microbiome to some extent. That is very valuable information.’

The study showed that eight of the parchment sheets were made from cowhide and one from the hide of a sheep. The animals are related to different breeds. The three sheets that the project was about were made from the hide of a bull in northern France in the period 1410-1420. The date was not determined by Schijlen’s analysis; it was already known from previous research on the handwriting and the illustrations. According to Schijlen, it is not yet possible to date the parchment using genetic analysis. ‘To do that, you would need reference genomes for animals living at that time, and we don’t have much information on those old breeds.’

Schijlen assumed that would be the end of this interesting diversion, but there might be a follow-up. The publication of the study has led to a request for a new and possibly even more exciting investigation, looking at ‘the last Da Vinci’. Schijlen: ‘It also involves a sheet of parchment, with an illustration attributed to Da Vinci that is thought could be a missing page from the book La Sforziada. We might be able to test that using DNA analysis.’ There is only one problem: money. ‘We are still looking for funding. But once we’ve got that, we should be able to start before the year is out.’

Master B

The three parchment sheets Schijlen studied came from a book of hours, a collection of Christian prayers and other texts. The pages of this book have become separated over time, but the book was probably part of the collection of the medieval bibliophile John, Duke of Berry. The illustrations of vine tendrils in the margins match those of the famous book of hours Belles Heures. That book was illustrated by the Van Lymborch brothers, who were commissioned by the duke. To be clear, the brothers were responsible for the wonderful illustrations elsewhere in the book, but they didn’t draw the tendrils; they were done by an unknown illustrator called Master B. where the ‘B’ stands for Belles Heures. Some of the books in the Duke’s collection have been lost. The sheets Schijlen investigated almost certainly come from one of the books that had been thought lost, of which 81 sheets have now been found.

Van Lymborch year

Fans of the work of the Van Lymborch brothers have plenty to celebrate in 2025. There is an exhibition (from 7 June to 5 October) of the famous book of hours Très Riches Heures in Musée Condé in Chantilly, north of Paris. This book is almost never put on display, but it has been partly unbound for restoration purposes. The Belles Heures (from New York) and Bible Moralisée (from Paris) are also in the exhibition. The Maelwael Van Lymborch museum in Nijmegen has organized various events to tie in with this exhibition. If you can’t make it to Nijmegen, you can admire the famous illustrations anyway on the museum’s website.

Bianca

La Sforziada is an ode to the Italian Sforza family. The book, which has a missing page, has been in Poland since the start of the sixteenth century. A sheet that could be the missing page, with a portrait of a young woman, turned up in a Christie’s auction in New York in 1998. The buyer purchased it for 21,550 dollars. Later examination suggested it could be the work of Leonardo da Vinci. The young woman in the portrait is Bianca Sforza, who would have been about 13 or 14 and would have just got married to Da Vinci’s patron. The portrait is thought to have been a wedding present. Bianca died a few months later. The portrait’s origins are the subject of debate and an investigation of the parchment could shed more light on the matter.

One of the parchment leaves from a medieval codex that Elio Schijlen researched. Margin decoration by “Master B.” Photo: Maelwael Van Lymborch House

One of the parchment leaves from a medieval codex that Elio Schijlen researched. Margin decoration by “Master B.” Photo: Maelwael Van Lymborch House